Biomedical science students’ perception of the use of role-play in learning stress and anger management skills

Submitted: 2 July 2023

Accepted: 17 November 2023

Published online: 2 April, TAPS 2024, 9(2), 51-59

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-2/OA3078

Soi Moi Chye1, Rhun Yian Koh1 & Pathiyil Ravi Shankar2

1Department of Applied Biomedical Science and Biotechnology, School of Health Science, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2IMU Centre for Education, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Abstract

Introduction: People skills play a crucial role in the professional development of Biomedical Scientists. A laboratory management and professional practice module was offered as part of the people skills development for Biomedical Science first-year students. This study aims to describe the use of role-play to teach stress and anger management skills to Biomedical Science students and reports on students’ opinions of role-play as a teaching-learning method.

Methods: Students were divided into groups with 10 or 11 students per group. Each group of students presented a role-play for 15 to 20 min. This was followed by reflections by the group, feedback from other groups, and the facilitators. At the end of the session, student feedback was taken by a questionnaire using both closed (using a 5‑point Likert scale) and open‑ended questions. Statistical evaluation of the collected data was carried out using SPSS version 28 for Windows.

Results: A total of 96 students from the 2021 and 2022 cohorts participated in the role-plays. The survey was completed by 48 students from the 2021 intake and 33 students from the 2022 intake. The overall response rate was 84.37%. Respondents perceived role-play to be enjoyable, useful, and helpful for developing stress and anger management skills. They wanted role-play to be used as a teaching-learning method in the future.

Conclusions: Role-play can be effective to teach stress and anger management skills to undergraduate Biomedical Science first-year students.

Keywords: Role-Plays, Stress and Anger Management Skills, Biomedical Science, Professional, Questionnaire, Feedback; Undergraduate

Practice Highlights

- Respondents perceived role-play to be enjoyable, useful, and helpful for developing stress and anger management skills.

- Role-play can be effective to teach stress and anger management skills to undergraduate Biomedical Science first-year students.

- Role-play was recommended to be used as a teaching-learning method in the future.

I. INTRODUCTION

People skills are the ability to communicate effectively with others, build relationships, and work collaboratively. People skills include active listening, empathy, conflict resolution, and teamwork. Anger and stress can impact people skills, especially interpersonal communication (Strumska-Cylwik, 2014). It is important to note that people who are easily angered and stressed often come from families that are disruptive, chaotic, and not skilled at emotional communication. Uncontrolled anger and stress can negatively affect physical health and emotional well-being and can lead to problems at work, in personal relationships, and in the overall quality of life (Armstrong, 2012). There is an important link between anger, stress, interpersonal skills, and emotional intelligence (Schutte et al., 2001). Bennett et al. (2016) reported that soft skills (people skills) are more critical for future employment than technical skills, and their enhancement has a lifelong impact. These skills are particularly important for health professionals due to the close relationship between them and their patients.

Health professionals are required to possess a technical background, which includes reasoning and critical judgment, as well as competency in communications, conflict resolution, negotiation, and decision-making (Morrell et al., 2020). A study among undergraduate medical students found a decline in students’ people skills, and a more technical approach replaced a more spontaneous and humane approach (Wahlqvist et al., 2005). Ahmad et al. (2014) concluded that most engineering students possess technical skills but lack people skills. One of the reasons is that teachers lack comprehensive knowledge and experience in teaching soft (people) skills to students (Ahmad et al., 2014). Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (2005) states that the development of soft (people) skills requires a student-centred approach. Similarly, Mohd-Amin and Mohd-Nor (2010) and Morris (2009) suggest that teachers should be more creative when devising teaching and learning strategies so that students’ people skills can be more effectively organised and developed. Curriculum quality and teachers have an impact on students’ listening, responding, questioning, and formulating abilities (Morris, 2009). These skills acquired by an individual assist them in optimising their performance and include communication skills, teamwork, leadership skills, problem-solving skills, critical thinking skills, time management, and emotional intelligence (Siu et al., 2021). Teachers are therefore vital to implementing people skills relevant to the courses they teach. At our university student evaluations of laboratory management and professional practice module indicated they were not satisfied with the teaching of these skills through lectures. Students indicated that the lectures were boring, not effective, and the content was already known. Thus, we used a different method of role-play to teach stress and anger management skills.

Role-play is defined as an approach to learning in which learners act out roles in case scenarios to provide targeted practice and feedback for the development of skill and competency (Nair, 2019). As a result, they gain a first-hand experience of human interactions and a better understanding of appropriate behavioural approaches to situations like those in real life. This approach emphasizes the learner’s need to know, self-direction, and varied experiences, contributing to the adoption of a problem-centred approach (Shankar et al., 2012). According to Harries and Raban (2012), role-play is a useful technique for engaging students in the learning process and environment. Through role-play, students can communicate and experience different situations and contexts, which can be used by teachers to develop students’ problem-solving, critical thinking, and creative skills. Furthermore, role-play allows students to experience a variety of different domains: cognitive, emotional, physical, and literacy domain (Beard et al., 1995). Additionally, role-play has been proven to be an effective method of developing skills such as active listening, problem-solving, empathy, teamwork, knowledge acquisition, and effective communication in various fields of training (Beard et al., 1995; Harden & Gleeson, 1975; Kim, 2018). Apart from this, role-play is an effective teaching strategy for health science students and is used by medical students to practice communication skills effectively and promote empathy and a more patient-centred approach to care (Ong et al., 2022). Based on the findings of Rønning and Bjørkly (2019), role-play in health sciences education enhances students’ therapeutic and communicative skills and facilitates personal and professional growth as it increases students’ ability to learn what it is like to be in others’ shoes and, through that experience, develop empathy and reflection. Role-play can be an effective tool for developing stress and anger management skills. It allows individuals to practice new behaviours and techniques in a safe and supportive environment, which can help to build confidence and improve overall well-being (Snowden & Rebar, 2018; Sutton, 2022).

The International Medical University (IMU), Bachelor of Science (Hons) in Biomedical Science programme is designed to produce work-ready graduates who are well-equipped with knowledge and are competent in practical, as well as people skills. The curriculum of the programme includes research-based teaching and problem-based learning, and students learn from experienced faculty. In addition to didactic large group teaching sessions (plenaries), the programme is also delivered through small group teaching sessions, such as problem-based learning, workshops, computer-aided learning, tutorials, seminars, presentations, etc. The learning outcomes of stress and anger management sessions are the definition of anger and stress; anger and stress management skills; contributing factors to stress and anger; and approaches to managing stress and anger engagement. The present study was conducted to explore the participants’ perception of the usefulness, understanding, enjoyment, and feedback of using role-play as a teaching-learning method for developing stress and anger management skills.

II. METHODS

Stress and anger management skills are a component of the laboratory management and professional practice module. This module is compulsory for first-year Biomedical Science students. Role-play was chosen to deliver stress and anger management skills because previous students were not satisfied with lectures as the teaching-learning method. Role play serves as a method of experiential learning in which learners assume various roles and engage in interactive experiences in diverse learning environments. The theory of experiential learning underscores the significance of acquiring knowledge through hands-on experience and subsequent reflection, constituting fundamental components of contemporary approaches to adult education (Nestel & Tierney, 2007).

The procedures for the role-play were based on Shankar et al. (2012) article. Shankar et al. had used role-plays to explore issues related to the health humanities among medical students. Here it was used to explore stress and anger management skills among biomedical science students. Table 1 shows the sequence of activities during the sessions. The addition of a guide or facilitator is necessary to maximize the benefits derived from role-plays (Cobo et al., 2011). The facilitators provide guidance to the learners before and after the sessions (Nakamura et al., 2011). First, the faculty explained how to prepare the role-play and gave an example of good quality and poor-quality role-play. Additionally, stress and anger management YouTube videos were also uploaded to the e-Learning portal for reference. Then, students were divided into groups with 10 or 11 students per group. During the third step, students could select the scenarios provided or create their own scenarios. Nevertheless, students were required to consult with faculty members regarding the role-play to address major learning issues. Having determined the topics, students began writing scripts and practicing the role play. Each group of students performed a role-play for 15 to 20 min and a presentation on contributing factors for stress and anger and the correct and incorrect approaches to handling stress and anger based on the scenario for 5 min. Finally, faculty members provided feedback to the students for further improvement.

|

Activities |

Duration |

|

1. A briefing on the role-play preparation procedures as well as YouTube videos on stress and anger management were uploaded to the e-Learning portal. |

1 hour |

|

2. Students were divided into groups with 10 or 11 students per group. |

10 minutes |

|

3. Selection and determination of topics, script preparation, and role-play practice. |

3 weeks |

|

4. Role-play performance, 15-20 minutes per group. Presentation of the contributing factors and correct and incorrect approaches to handling stress and anger, 5 minutes per group. |

3 – 4 hours |

|

5. Faculty members provided feedback to the students for further improvement. |

30 minutes |

Table 1. An overview of the activities and duration of different components of the role-play session

A total of 96 students from the 2021 and 2022 cohorts participated in the role-plays. The sample size calculation is shown below.

The calculator.net (www.calculator.net) sample size calculator was used. The confidence level was 95%, and the margin of error was set at 5%, assuming a population % of 50% and a population size of 96. The recommended sample size using these parameters was 77.

The questionnaire used to obtain student feedback is based on that used by Shankar et al. (2012) with some modifications as shown in Appendix I. In that study, original role-play questionnaires were used by students from the third, fifth, and sixth semesters of the Medical Humanities module. Thus, some of the questions, such as “Have you been exposed to the use of role-plays for educational objectives before?” “Are you aware of the use of role-plays in medical education elsewhere?” were removed. The rest of the questions are similar. Feedback was obtained from the Biomedical Sciences programme first-year students. The questionnaires contained both close-ended (using a 5-point Likert scale) and open questions. The survey was conducted after the students completed the role-play from 18 to 22 October 2022. Participants were informed about the study’s objectives before participating, and they were required to provide written informed consent.

Data were analysed using MS Excel and SPSS version 28. The distribution of the scores for enjoyment, understanding, and usefulness were compared using the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p<0.05). The distributions were not normal and hence median and interquartile range were used as measures of central tendency and variation. The median (interquartile range) scores among the two cohorts and among males and females were compared using the independent samples median test (p<0.05). Each open comment was analysed systematically in an iterative manner by creating a thematic coding structure. As new themes emerged, the coding structure was revised, and the previous comments were reread for consistency. Moreover, the comparison of the difference between cohorts and gender for the perception of enjoyment, understanding, and usefulness was conducted because role-plays for cohort 2021 were conducted online due to Malaysia’s movement control order during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the cohort 2022 role-plays were conducted physically. Studying gender differences in the perception of different educational interventions may be important because behaviours, styles of social interaction, academic motivations, and choices may be different across genders, and it helps identify disparities and promote equity and inclusivity in the classroom. It allows educators to address any biases or barriers that may hinder students’ educational opportunities and success (Myaskovsky et al., 2005).

III. RESULTS

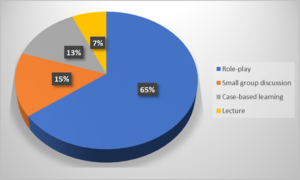

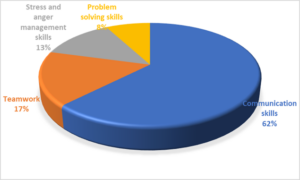

A total of 96 students from 2021 (56) and 2022 cohorts (40) participated in the role-plays. A total of 81 students (overall response rate of 84.1%) participated in the survey. Our results show forty-eight students were from the 2021 cohort and the cohort response rate was 85.7%, Thirty-three students were from the 2022 cohort and the cohort response rate was 82.5%. The percentage of males was 22.22% and females were 77.78%. According to Figure 1, 65% of students prefer role-play to teach stress and anger management skills, followed by small group discussions (15%), case-based learning (13.3%), and lectures (6.7%). This is based on question 8 of the questionnaire. Figure 2 illustrates the skills students learned during role-play. Communication skills were mentioned by 62.3% of the respondents, followed by teamwork (16.9%), stress and anger management (12.9%), and problem-solving skills (7.8%). This is based on question 4 of the questionnaire. The data that supports the study is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23607033.v1.

Figure 1. Instructional methods preferred by students to learn stress and anger management skills

Figure 2. Skills students learned through role-plays

Sixty-six students (90.4%) mentioned role-plays can be used for future topics/modules while 7 students (9.6%) were not in favor (based on question 9 of the questionnaire).

The perceptions of students about the use of role-play in anger and stress management were measured on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being the least and 5 being the highest. Table 2 shows the median and interquartile range of the scores for enjoyment, understanding, and usefulness among the two cohorts and among male and female students. There was no statistically significant difference in the scores between the two cohorts and between male and female students.

|

Items |

Categories |

Median (IQR) |

p-value |

|

Enjoyment |

BM121 |

4.00 (1) |

0.948 |

|

BM122 |

4.00 (2) |

||

|

Female |

4.00 (1) |

0.717 |

|

|

Male |

4.00 (1) |

||

|

Understanding |

BM121 |

4.00 (0) |

0.197 |

|

BM122 |

4.00 (1) |

||

|

Female |

4.00 (1) |

0.404 |

|

|

Male |

4.00 (0) |

||

|

Usefulness |

BM121 |

4.00 (1) |

0.954 |

|

BM122 |

4.00 (1) |

||

|

Female |

4.00 (1) |

0.132 |

|

|

Male |

4.00 (0) |

Table 2. Summary of survey results of enjoyment, understanding, and usefulness scores among the two cohorts and among male and female students

|

Theme |

Quotes |

|

Knowledge and understanding |

“By implementing the solutions for anger and stress management to our role-play, we are able to understand its importance and apply it to our daily lives.” “Help students to understand a particular stressful situation by assigning the students to act out, involving in script and coming up with an outcome. Hence, they see the whole picture clearly and more related to it.” “Yes, it covers different aspects including family, peers, and colleagues. So, student get to understand different circumstances.” |

|

Usefulness |

“Yes, all the scenarios showed stress and anger in different possible situations we may encounter.” “Role-play allows us to experience and understand the emotions involved in related scenarios and better prepare us for the future.” |

|

Enjoyable |

“Role play should be considered more than lectures because it is more effective, and students prefer enjoyable way of studying.” “Can relate more by looking at real life acting on situation, more fun and engaging.” “It’s livelier and fun, making it easier to learn.” |

|

Communication |

“It helps us to know that communication skills are important, which certainly helps to clear doubt and can release some stress.” “Communication skills when preparing the role play and presentation skills when acting.” “The communication skill is the soft skill I have learnt from this role-play. It is because our group had several discussions and rehearsals before the role-play. During these times, I need to express my view clearly and fluently, especially the creative ideas and critics. I have learnt how to negotiate with others’ opinions too.” |

|

Teamwork |

“I think because of our teamwork we were able to overcome the difficulties we might have had in the beginning.” “It makes me understand the topic more and helps me be more collaborative with my peers.” |

Table 3. Perception of students regarding the role plays

Regarding students’ perceptions of the appropriateness of the scenarios covered during the role-play the role-play most students answered yes, while only one student answered no. Students stated, “All the scenarios showed stress and anger in different possible situations we may encounter.” “It covers different aspects including family, peers, and colleagues. So, students get to understand different circumstances.” “Because they were those that will occur one way or another in real life be it in a work setting or a school setting. These scenarios were a stepping stone towards the real world and all the possibilities it has to offer.” From the feedback, we concluded that the reasons for the appropriateness of the scenarios covered during the role-play included they were able to see how to manage stress and anger in different situations.

Moreover, 90.4% of the students responded that role-play should be used in future topics/modules. Suggestions for improving the use of role-plays during future sessions were the stage to perform the role-play is too small, and the background is not appropriate. Comments also include improving briefing, marking rubrics, feedback, and expectations for students further. Each group can have a lesser number of participants making fair and equal work distribution, and more real-life case scenarios can be provided.

IV. DISCUSSION

This study explores the contribution of role-play in teaching stress and anger management skills. Results showed that students perceived role-play to be enjoyable, useful, and helpful for developing stress and anger management skills. According to Harries and Raban (2012), role-play engages many brain regions including language, emotion, cognition, and motor functions. It, therefore, stimulates participants’ cognitive and affective engagement while they have fun. In line with this finding, our students found role-play to be a fun, enjoyable, effective, useful, easy, engaging, interactive, and interesting method for learning stress and anger management skills. Eggen and Kauchak (2006) mentioned that the use of a specific teaching & learning method helps encourage students to apply soft skills and further enhance additional skills possessed by students. In agreement with this study, our results showed that role-play provided students with an opportunity to develop communication skills, teamwork skills, and problem-solving abilities. It has been proven by Beard et al. (1995), that role-play allows children to communicate and experience different situations and contexts which teachers can use to develop students’ problem-solving, critical thinking, and creativity skills.

Several studies have demonstrated that providing feedback to students can improve their learning outcomes while providing feedback from teachers can improve their performance in the classroom (Dinkmeyer & Losoncy, 1980; Schutz & Weinstein, 1990). Structured feedback helped students to reflect on both what had taken place in each role-play as well as the value of role-play after participating in the session. This is true for first-year students who previously had no exposure to professional practice and are therefore dependent on feedback and guidance. Further, our experience with role-play is open to improvement in subsequent courses. Based on the feedback, students commented that the marking rubric for role-play can be further improved. A study suggested that the assessment of student role-play learning outcomes could be improved using validated rubrics and published examples (Carlin et al., 2011). Considering this, we will revise our marking rubric in accordance with published examples for the following cohort. According to feedback from the 2021 students, role-play should be conducted physically, while feedback from the 2022 students indicated that the performance stage was too small, and the background and props could be improved. It is important to note that there are differences in feedback from both cohorts because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The role-play for the 2021 cohort was conducted online, whereas the role-play for 2022 was conducted face-to-face. There were no differences in the median scores between males and females and between the two cohorts. With the reduction in the COVID-19 pandemic, the university is slowly moving toward face-to-face teaching-learning. For subsequent cohorts, role-plays will be conducted physically.

Next, it would be beneficial to improve briefings, feedback, and expectations for students. We provided feedback and expectations for students during the module coordinator briefing and uploaded the briefing recorded video to the e-Learning portal and provided feedback to students after the role-play. This can improve further for subsequent cohorts because Al-Hattami (2019) suggests that feedback is constructive if it provides students with clear expectations about their performance, encourages students to increase their efforts, and describes their future learning goals. Feedback should be provided to all students consistently, fairly, and immediately after they have completed the task to enhance their learning (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Constructive feedback has a significant impact on a student’s learning (Lipnevich & Smith, 2009). Thus, we will provide more effective feedback to the next cohort of students. The other comment is the request for smaller group sizes, making fair and equal work distribution. The current grouping of students is 10-11 students per group. Therefore, it is possible that the distribution of work among students is not equal. For the next cohort, the grouping should be decreased to 5-6 students per group.

The Division of Laboratory Systems of the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Division of Laboratory Systems, 2018) and the American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP) (American Society for Clinical Pathology, n.d.) have developed guidelines regarding the required competencies for laboratory personnel. Among the different competencies, communication skills, leadership and education of other laboratory personnel, other healthcare professionals and consumers are mentioned. A study showed that stress and anger management skills play an important role in interpersonal communication (Strumska-Cylwik, 2014). According to Prabhu et al. (2016), anger is often a maladaptive reaction to the stress of coping in a stressful environment, which may lead to an increase in conflict and discomfort. A wide range of problems have been linked to anger, including alcohol and substance abuse, emotional of insecurity, and even self-harm. Many students have anger episodes that last for approximately a day, and a significant majority found it difficult to concentrate on academic work and maintain healthy relationships during these episodes (Dollar et al., 2018). In accordance with Safari et al. (2014), training in anger management, stress management, and interpersonal communication skills can significantly improve the emotional intelligence of students. Managing anger and stress effectively can have a significant impact on mental health, academic performance, interpersonal relationships, and overall well-being. Thus, if Biomedical Science students are well-equipped with these techniques, they will be able to better engage with the learning process, improve problem-solving abilities, promote healthy coping mechanisms, cultivate positive interpersonal relationships, maintain physical and mental health, improve academic performance, be able to address physical abuse, criminal behaviour, difficulty concentrating, sleep disturbances, and ensure long-term success.

There were also limitations to this study. First, the participants are new first-year, semester 1 students. This is their first-time doing role-play, and they do not have any prior experience in this regard. Thus, educational effectiveness could only be determined indirectly. Students’ stress and anger management skills were not measured before or after the role-play, and much of the evidence for its effectiveness is based on anecdotal evidence. Second, in general, role-play alone probably contributes along with other factors to stress management and anger management skills development. Therefore, it is difficult to evaluate the effects of a single educational method. Additionally, it is important to recognize that students learn in different ways. Third, there may have been a certain amount of response bias, as the student is familiar with the researcher and may have subconsciously or consciously given the response that he or she thinks the researcher expects to hear. This study analysed only quantitative data from a structured questionnaire. Although a few open-ended questions were incorporated to analyse students’ perceptions, they were not explored in depth. Moreover, this study was conducted using a modification of an existing questionnaire. No validation was carried out. Future studies should involve more role-plays and participants to clarify the effects of the role-play and examine the long-term effects of repeated role-play.

V. CONCLUSION

Most students found role-play to be enjoyable, useful, and helpful for understanding stress and anger management skills, regardless of their cohort or gender. By using role-play, students gain a better understanding of the objectives and factors contributing to stress and anger and the development of management skills because role-play provides students with an experiential learning opportunity. Students actively engage in simulated situations, allowing them to better grasp the complexities of these emotions. During role-play, students must think critically and make decisions based on the roles they’re portraying. They must analyse situations, identify triggers, and consider appropriate management strategies, promoting higher-order thinking skills. Dealing with stress and anger often involves problem-solving. Role-play challenges students to find effective solutions to conflicts and challenges that arise within the scenarios, encouraging them to develop creative problem-solving skills. After the role-play, students can receive feedback from peers or instructors. This feedback helps them understand the effectiveness of their chosen strategies and encourages reflective thinking about their decisions and actions. Engaging in role-play can lead to increased self-awareness as students reflect on their own emotional responses and behaviours in stressful situations. Thus, it is recommended that role-play be incorporated into future teaching methods.

Notes on Contributors

Soi Moi Chye was involved in facilitating the role-play and providing constructive feedback to students. She was involved in the concept and design of the study, writing and applying for ethical approval from the ethical committee. She helped in revising the manuscript. She implemented the project, conducted data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript.

Rhun Yian Koh was involved in facilitating the role-play and providing constructive feedback to students. She was also involved in implementing the research project, data analysis and interpretation, and critical review and revision of the manuscript.

Pathiyil Ravi Shankar was involved in the conception and design of the study, data analysis, and interpretation, critical revision of the proposal and manuscript, approved the final manuscript and carefully copyedited the manuscript. He helped in revising the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study obtained approval from International Medical University-Joint Committee on Research & Ethics (IMU-JC); the grant number is IMU 558-2022.

Data Availability

The data associated with this study is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23607033.v1.

Funding

This study was supported by International Medical University; the grant number is IMU 558-2022.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

Ahmad, E., Asri, S., Suhaili, P., & Jamaludin, J. (2014). Applications of soft skills in engineering programme at polytechnic Malaysia. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 140, 115-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.395

Al-Hattami, A. (2019). The perception of students and faculty staff on the role of constructive feedback. International Journal of Instruction, 12(1), 885-894. https://doi.org/10.29333/IJI.2019.121 57A

American Society for Clinical Pathology. (n.d.). Personnel standards for laboratory professionals (policy number 04-01). https://www.ascp.org/content/docs/default-source/policy-statements/ascp-pdft-pp-personnel-standards.pdf?sfvrsn=2

Armstrong, M. (2012). Armstrong’s handbook of management and leadership: Developing effective people skills for better leadership and management (3rd ed.). Kogan Page Publisher.

Beard, R. L., Salas, E., & Prince, C. (1995). Enhancing transfer of training: Using role-play to foster teamwork in the cockpit. The International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 5(2), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327108ijap0502_1

Bennett, D., Richardson, S., & Mackinnon, P. (2016). Enacting strategies for graduate employability: How universities can best support students to develop generic skills. Curtin University. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4094.8886

Carlin, N., Rozmus, C., Spike, J., Willcockson, I., Seifert, W., Chappell, C., Hsieh, P., Cole, T., Flaitz, C., & Engebretson, J. (2011). The health professional ethics rubric: Practical assessment in ethics education for health professional schools. Journal of Academic Ethics, 9, 277-290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-011-9146-z

Cobo, A., Conde, O., Quintela, M. Á., Mirapeix, J. M., & López-Higuera, J. M. (2011). On-line role-play as a teaching method in engineering studies. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.3926/jotse.2011.13

Dinkmeyer, D., & Losoncy, L. E. (1980). The encouragement book: Becoming a positive person. Prentice Hall.

Division of Laboratory Systems. (2018, November 15). Competency guidelines for laboratory professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dls/competency-guidelines-laboratory-professionals.html

Dollar, J. M., Perry, N. B., Calkins, S. D., Keane, S. P., & Shanahan, L. (2018). Temperamental anger and positive reactivity and the development of social skills: Implications for academic competence during preadolescence. Early Education and Development. 29(5), 747-761. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2017.1409606

Eggen, P. D., & Kauchak, D. P. (2006). Strategies for teacher: Teaching content and thinking skills (5th ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

Harden, R. M., & Gleeson, F. A. (1975). Assessment of clinical competence using an objective structured clinical examination. The BMJ, 1, 447–451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.5955.447

Harries, J., & Raban, B. (2012). Play in the early years: Role play. Essential Resources.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487k

Kim, J. H. Y. (2018). Effects of role-play for problem-solving skills and engagement in online forums. Educational Technology to Improve Quality and Access on a Global Scale, 91-109. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66227-5_8

Lipnevich, A. A., & Smith, J. K. (2009). Effects of differential feedback on students’ examination performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 15(4), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017841

Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia. (2005). Modul pembangunan kemahiran insaniah (soft skills). UPM Press. https://upmpress.com.my/product/modul-pembangunan-kemahiran-insaniah-soft-skills-untuk-institusi-pengajian-tinggi-malaysia/

Mohd-Amin, N. F., & Mohd-Nor, S. (2010). Tinjauan terhadap guru di Sekolah Menengah Teknik Negeri Johor terhadap penerapan kemahiran generik dalam proses pengajaran dan pembelajaran mata pelajaran kejuruteraan. Malaysian Academic Library Institutional Repository.

Morrell, B., Eukel, H. N., & Santurri, L. E. (2020). Soft skills and implications for future professional practice: Qualitative findings of a nursing education escape room. Nurse Education Today, 93, Article 104462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104462

Morris, A. (2009). The stretched academy: The learning experience of mature students from under-represented groups. University of Lincoln.

Myaskovsky, L., Unikel, E., & Dew, M. (2005). Effects of gender diversity on performance and interpersonal behavior in small work groups. Sex Roles, 52(9/10), 645–657.

Nair, B. T. (2019). Role play – An effective tool to teach communication skills in pediatrics to medical undergraduates. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8, 18.

Nakamura, T., Taguchi, E., Hirose, D., Masahiro, I., & Takashima, A. (2011). Role-play training for project management education using a mentor agent. 2011 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conferences on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology. https://doi.org/10.1109/wi-iat.2011.256

Nestel, D., & Tierney, T. (2007). Role-play for medical students learning about communication: Guidelines for maximising benefits. BMC Medical Education, 7, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-7-3

Ong, C. Y., Yee, M. M., Soe, K. M., Abraham, R. E., Tan, O. J. H., & Ong, E. L. C. (2022). Role-playing in medical education: An experience from public role-players. Educación Médica, 23(6), Article 100767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edumed.2022.100767

Prabhu, G. S., Tam, J. M. Y., Amalaraj, J. J. P., Tan, E. Y. J., & Kumar, N. (2016). Anger management among medical undergraduate students and its impact on their mental health and curricular activities. Education Research International, 2016, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7461570

Rønning, S. B., & Bjørkly, S. (2019). The use of clinical role-play and reflection in learning therapeutic communication skills in mental health education: An integrative review. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 10, 415-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S202115

Safari, A., Jafary, M. R., & Baranovich, D. L. (2014). The effect of anger management, intrapersonal communication skills and stress management training on students’ emotional intelligence (EQ). International Journal of Fundamental Psychology and Social Sciences, 4(2), 31-38.

Schutte, N. S., Schuettpelz, E., & Malouff, J. M. (2001). Emotional intelligence and task performance. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 20(4), 347-354. https://doi.org/10.2190/J0X6-BHTG-KPV6-2UXX

Schutz, P. A., & Weinstein, C. E. (1990). Using test feedback to facilitate the learning process. Innovation Abstracts NISOD, 12(6), 1-2.

Shankar, P. R., Piryani, R. M., Singh, K. K., & Karki, B. M. S. (2012). Student feedback about the use of role-plays in Sparshanam, a medical humanities module. F1000Research, 1, 65. http://dx.doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.1-65.v1

Siu, J. L. R., Salazar, R. E. R., & Montaño, L. F. (2021). Habilidades blandas y el desempeño docente en el nivel superior de la educación. Propósitos Y Representaciones, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9n1.1038

Snowden, S., & Rebar, S. (2018). Anger management workbook for kids: 50 Fun activities to help children stay calm and make better choices when they feel mad. Althea Press.

Strumska-Cylwik, L. (2014). Expression of fear and anger in the context of interpersonal communication. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 7(1), 173.

Sutton, J. (2022, July 22). Role play in therapy: 21 scripts & examples for your session. Positive Psychology. https://positivepsychology.com/role-playing-scripts/#google_vignette

Wahlqvist, M., Mattsson, B., Dahlgren, G., Hartwig-Ericsson, M., Henrique, B., Hamark, B., & Hösterey-Ugander, U. (2005). Instrumental strategy: A stage in students’ consultation skills training? Observations and reflections on students’ communication in general practice consultations. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 23(3), 164–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/02813430510018646

*Dr Pathiyil Ravi Shankar

IMU Centre for Education,

International Medical University

Jalan Jalil Perkasa 19, Bukit Jalil

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 57000

Email: ravi.dr.shankar@gmail.com