Using action research to evaluate a pre-registration pharmacist training and assessment framework in Singapore: Results from Phase 1 implementation

Submitted: 28 February 2025

Accepted: 24 June 2025

Published online: 6 January, TAPS 2026, 11(1), 32-43

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2026-11-1/OA3683

Sei Keng Koh1,2, Li Wen Loo1,2, Zhining Goh1,3, Dujeepa D. Samarasekera4, Carolyn Ching Ching Ho1, Paul John Gallagher5, Wai Keung Chui5 & Camilla Ming Lee Wong1,6

1Chief Pharmacist’s Office, Ministry of Health, Singapore; 2Division of Pharmacy, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 3Department of Pharmacy, Ng Teng Feng General Hospital, Singapore; 4Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 5Department of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 6Division of Allied Health & Pharmacy, Sengkang Health, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: An action research-guided national pre-registration pharmacist (pre-reg) training programme was implemented in two phases: July 2023 to January 2024, and May 2024 to January 2025. The programme is based on professional activities (PAs) required for independent practice, aligning with the Singapore Development Framework for Pharmacists’ competency standards. Workplace-based assessments (WBAs) graded using a supervision scale form the assessment framework.

Objective: This study aims to evaluate the appropriateness of PAs for training and assessment while gathering feedback on user experience.

Methods: Pre-regs and preceptors were selected through purposive sampling with randomisation. Data was collected via online surveys and group interviews. Interviews were conducted separately for pre-regs and preceptors using similar question guides, and audio-recorded, transcribed, then thematically analysed.

Results: Responses from 14 pre-regs and 16 preceptors during Phase One highlighted the strengths, challenges, and recommendations for improving PAs and WBA templates. Pre-regs felt the framework supports a seamless transition to post-course training, while preceptors recognised their role in ensuring that pre-regs attain appropriate supervision levels. The framework was positively received, with well-performing elements retained and areas for improvement identified. Insights gained from action research informed refinements to the framework. Action research for Phase Two is ongoing, with results forthcoming.

Conclusion: The study’s findings led to framework modifications for Phase Two implementation from May 2024. Adjustments were made to individual PAs and WBA forms, with consolidated guidance provided in a user toolkit for dissemination.

Keywords: Action Research, Pre-registration Pharmacist Training, Entrustable Professional Activities

Practice Highlights

- Professional Activities (PA) for direct and indirect patient care (pharmaceutical companies and regulatory authority), were developed for the national pre-registration pharmacists (pre-regs) training and assessment framework and implemented in phases.

- Action research approach was used to identify areas of improvement for framework enhancement.

- Key areas of enhancement encompass three main aspects: improving the clarity of PA documents, validity of the indirect patient care PAs, and assessment tools and administrative processes; strengthening preceptors’ skills in conducting workplace-based assessments (WBAs), and enhancing pre-registration pharmacists’ engagement with PAs and WBAs.

- A Pre-Registration Training Advisory Committee will be appointed to support the full implementation of the framework in May 2025.

I. INTRODUCTION

In Singapore, pharmacy graduates must complete 12 months of pre-registration training to be eligible for registration with the Singapore Pharmacy Council (SPC). Training for local graduates is divided into two segments: Pre-reg 1 (PR1), a 22-week programme within the National University of Singapore (NUS) Bachelor of Pharmacy (Honours) course and Pre-reg 2 (PR2), a 30-week post-course programme (Figure 1). PR1 rotations are completed in primary care (i.e. retail pharmacy or polyclinic) and either an indirect patient care setting (i.e. pharmaceutical company or regulatory authority) or community hospital. The training was guided by the SPC Competency Standards Framework which articulates 301 competency standards across nine functional areas (Singapore Pharmacy Council, 2010).

Figure 1. Overview of a Pre-Registration Pharmacist’s Journey

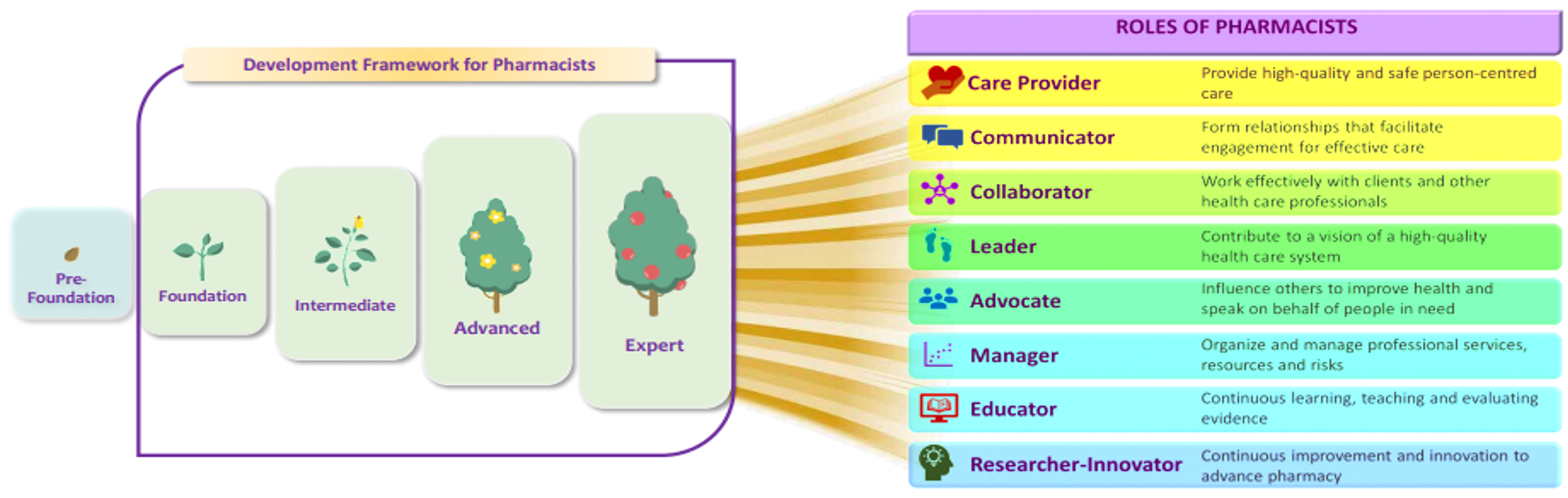

In 2020, the Chief Pharmacist’s Office introduced the Development Framework for Pharmacists (DFP), defining competency continuum from foundation to advanced practice across eight key roles aligned with NUS educational outcomes (Ministry of Health, Chief Pharmacist’s Office, 2024) (Figure 2).

Copyright © Ministry of Health, Singapore (2024). Version 2.0: June 2024

Figure 2. Continuum of Competency for Development of Pharmacists Towards 8 Key Roles

To facilitate a seamless transition from school to workplace, the Pre-registration Competency Standards Framework Review Committee (PRCSFRC) was appointed in 2021 to align educational outcomes and pre-registration training with the DFP. The committee developed a training and assessment framework with key features including:

- Competency blueprint for Day-1 Pharmacists adapted from DFP standards

- 10 Professional Activities (PAs) proposed as macro-outcomes for training (Table 1)

- Workplace-based assessments as main assessment modality

- A 5-level supervision scale to guide progression towards independent practice (Figure 3)

|

Professional Activities for Pre-Registration Pharmacists Training |

|

|

1 |

Develop and implement a care plan |

|

2 |

Accurate supply of health products |

|

3 |

Educate patients on the appropriate use of health products |

|

4 |

Respond to drug information or health product enquiry |

|

5 |

Collaborative partnerships with patients, and the pharmacy and interprofessional teams |

|

6 |

Develop a Continuous Professional Development (CPD) plan |

|

7 |

Prepare documents for regulatory decision making and/or compliance |

|

8 |

Handle/manage the activities relating to the roles of a Responsible Person for the licences/regulatory requirements |

|

9 |

Support project planning and data analysis |

|

10 |

Develop communication materials for healthcare professionals and public |

Table 1. Professional Activities for Phase-1 Pre-Registration Pharmacists Training

Figure 3. Supervision Scale Used for Assessing Pre-registration Pharmacists’ Professional Activities

This framework uses PAs adapted from Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) (Cate, 2018). EPAs are units of professional work that can be fully entrusted to an individual trainee, once they have demonstrated the needed ability to execute them unsupervised, and this requires the integration of multiple competencies (Cate, 2005). The impetus to adopt PAs for training and assessment included the potential of an EPA-based curriculum to link clinical training and assessment to the actual work that pharmacists do on a day-to-day basis (Hennus et al., 2022). This approach also provides scaffolding for workplace-based training by offering a safe and evidence-based way to facilitate the development of skills and knowledge (Richardson, 2024). EPAs are gaining attention as a practical method to assess competencies in pharmacy practice (Abeyaratne & Galbraith, 2024). Countries like USA, UK and Australia have developed core EPAs for their pharmacy graduates and for pre-registration training (Abeyaratne & Galbraith, 2023; Abeyaratne & Galbraith, 2024; Haines et al., 2017; Richardson, 2024). EPAs were also implemented locally in medical, nursing and allied health professions (Goh et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2020; Zainuldin & Tan, 2023a; Zainuldin & Tan, 2023b; Zhou et al., 2022).

The framework was implemented in phases, with Phase 1 involving 15 pre-registration pharmacists undergoing their PR1 rotations in July to September 2023 and November 2023 to January 2024. Phase 2 followed up with Phase 1 participants and included the entire second cohort of BPharm (Hons) students entering PR1. Action Research was used to identify problems, design solutions, and evaluate the impact of these solutions.

The research aims were to:

- Review the appropriateness of entry-to-practice pharmacists’ scope of practice as described in the PAs and

- Gather feedback on the assessment framework from preceptors and pre-registration pharmacists.

II. METHODS

A. Research Design

Practical Action Research was employed as a research strategy, coupled with both qualitative and quantitative content analysis. The research model is operational (technical), adopting an iterative approach of “Plan-Act-Observe-Reflect” (George, 2024). For the quantitative analysis, online surveys were disseminated to both pre-registration pharmacists (pre-reg) and their preceptors at the end of each rotation. The survey questions focused on three broad areas of (i) Content validity and reliability, (ii) Process and (iii) Comfort and Confidence. The qualitative analysis included group interviews with the pre-regs and their preceptors at the end of each rotation.

The survey and interview questions were developed based on the objectives of the action research cycle, informed by literature on EPAs. These were then validated by sharing with content experts from the pre-registration training and development committee and piloted with the first cycle collection of data. The questions relevant items were then enhanced for the subsequent cycles. This pretesting of the interview questions helped to identify unclear or ambiguous statements (Castillo-Montoya, 2016; Dikko, 2016).

B. Setting

The study was conducted in multiple sites across Singapore. Participating sites for indirect patient care included three pharmaceutical multinational companies. Participating sites for direct patient care included three retail pharmacy chains and one polyclinic (primary care) group.

C. Sample and Sampling Method

Pre-regs were posted to the training sites by the university. Fifteen pre-regs posted to the study sites for both rotations were invited via email to participate in the study. Nine female and six male pre-regs (n=15) were recruited. Twenty-four preceptors trained in the new framework were assigned to supervise these 15 pre-regs and invited to participate in the study. Each pre-reg is assigned one preceptor per rotation block, while each preceptor may precept up to two pre-regs per rotation block. Nineteen preceptors participated in the study.

D. Data Collection and Analysis

Data for this study was collected via an anonymous electronic survey, with responses analysed using descriptive statistics. Following the survey, group interviews were conducted both face-to-face and virtually. Qualitative data were obtained from free-text responses within the survey as well as from in-depth, audio-recorded group interviews, which were transcribed verbatim. Group interviews were held separately for pre-registration pharmacists (PRPs) and preceptors, utilising the same semi-structured interview guide to ensure consistency across cohorts. Each interview was facilitated by two trained pharmacist interviewers. To enhance credibility and trustworthiness, all transcripts underwent member-checking and peer debriefing. Coding was conducted inductively, with two researchers independently coding the transcripts before reconciling any discrepancies through consensus meetings. Thematic analysis was undertaken to interpret the qualitative data, enabling the identification of nuanced themes that complemented the broader trends observed in the survey findings.

E. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by both the Singapore Health Services (SingHealth) and NUS Institution Review Boards. Informed consent was obtained from the pre-regs and preceptors. Participation in the study was purely voluntary.

III. RESULTS

A. Online Survey Results

Fourteen (93%) pre-regs and 16 (84%) preceptors responded to the online survey. One pre-reg did not respond despite multiple reminders. Majority of the pre-regs (13/14, 92.9%) agreed that the framework prepared them well for their future role as a pharmacist. They felt that the PAs adequately described the scope of work of a pharmacist and the supervision levels were pegged appropriately for entry-to-practice. Preceptors assessed them fairly and they had the resources and support that they needed from the institutions. There was uncertainty about the ease and efficiency of the system for submission of assessment outcomes and inputs; as well as pre-regs being able to pass rotations under the framework. Survey results are in Table 2.

|

No |

Question |

Rating* |

Pre-Registration Pharmacists (n=14) (%) |

Question |

Rating* |

Preceptor (n=16) (%) |

|

1 |

I feel that the revised training and assessment framework will prepare me well for my future role as a pharmacist. |

SA |

2 (14.3) |

I feel that the revised training and assessment framework will prepare pre-registration pharmacists well for their future role as a pharmacist. |

SA |

3 (18.8) |

|

A |

11 (78.6) |

A |

13 (81.2) |

|||

|

UN |

1 (7.1) |

UN |

0 |

|||

|

DA |

0 |

DA |

0 |

|||

|

SDA |

0 |

SDA |

0 |

|||

|

2 |

The Professional Activities define the scope of work of an entry-level pharmacist well. |

SA |

1 (7.1) |

The Professional Activities adequately define the scope of work of an entry-level pharmacist well. |

SA |

3 (18.8) |

|

A |

12 (85.7) |

A |

11 (68.8) |

|||

|

UN |

1 (7.1) |

UN |

2 (12.5) |

|||

|

DA |

0 |

DA |

0 |

|||

|

SDA |

0 |

SDA |

0 |

|||

|

3 |

I believe the Professional Activities will be assessed appropriately and sufficiently to reflect my actual performance ability. |

SA |

1 (7.1) |

The Professional Activities are pegged at an appropriate level for entry to pharmacy practice. |

SA |

2 (12.5) |

|

A |

11 (78.6) |

A |

13 (81.3) |

|||

|

UN |

2 (14.3) |

UN |

1 (6.3) |

|||

|

DA |

0 |

DA |

0 |

|||

|

SDA |

0 |

SDA |

0 |

|||

|

4 |

I believe the preceptors will be fair when assessing me. |

SA |

4 (28.6) |

I believe I will be able to assess my pre-registration pharmacists fairly. |

SA |

3 (18.8) |

|

A |

10 (71.4) |

A |

13 (81.3) |

|||

|

UN |

0 |

UN |

0 |

|||

|

DA |

0 |

DA |

0 |

|||

|

SDA |

0 |

SDA |

0 |

|||

|

5 |

I have a good working knowledge of how the revised training and assessment framework works.

|

SA |

1 (7.1) |

I have a good working knowledge of how the revised training and assessment framework works. |

SA |

1 (6.3) |

|

A |

8 (57.1) |

A |

14 (87.5) |

|||

|

UN |

5 (35.7) |

UN |

1 (6.3) |

|||

|

DA |

0 |

DA |

0 |

|||

|

SDA |

0 |

SDA |

0 |

|||

|

6 |

I believe the training site will be adequately resourced to deliver pre-reg training using the revised framework (e.g. time given for assessments, sufficient number of preceptors). |

SA |

1 (7.1) |

My training site is adequately resourced to deliver pre-registration training using the revised framework. |

SA |

3 (18.8) |

|

A |

10 (71.4) |

A |

8 (50.0) |

|||

|

UN |

3 (21.5) |

UN |

2 (12.5) |

|||

|

DA |

0 |

DA |

3 (18.8) |

|||

|

SDA |

0 |

SDA |

0 |

|||

|

7 |

I am confident that I will get adequate help and guidance from my preceptors to manage the workload with the revised training and assessment framework. |

SA |

2 (14.3) |

I am confident that my pre-registration pharmacists will get adequate help and guidance to manage the case loads with the revised assessment framework. |

SA |

2 (12.5) |

|

A |

8 (57.1) |

A |

12 (75.0) |

|||

|

UN |

4 (28.6) |

UN |

2 (12.5) |

|||

|

DA |

0 |

DA |

0 |

|||

|

SDA |

0 |

SDA |

0 |

|||

|

8 |

There is an easy and efficient system of submission online, after assessments and evaluations are completed. |

SA |

2 (14.3) |

There is an easy and efficient system of submissions after assessments and evaluations are completed. |

SA |

1 (6.3) |

|

A |

5 (35.7) |

A |

4 (25.0) |

|||

|

UN |

6 (42.9) |

UN |

10 (2.5) |

|||

|

DA |

0 |

DA |

1 (6.3) |

|||

|

SDA |

1 (7.1) |

SDA |

0 |

|||

|

9 |

I am confident about passing this rotation under the revised training and assessment framework. |

SA |

1 (7.1) |

I am confident about my pre-registration pharmacists passing this rotation under the revised training and assessment framework. |

SA |

2 (12.5) |

|

A |

7 (50.0) |

A |

11 (68.8) |

|||

|

UN |

6 (42.9) |

UN |

3 (18.8) |

|||

|

DA |

0 |

DA |

0 |

|||

|

SDA |

0 |

SDA |

0 |

Rating*: Strongly Agreed (SA), Agree (A), Unsure/Neutral (UN), Disagreed (DA), Strongly disagreed (SDA)

Table 2. Results for Online Survey (Pre-Registration Pharmacists and Preceptors)

Qualitative comments were sought from pre-regs and preceptors on their perceived benefits and concerns of the PA-based framework compared to the previous competency-based one. For benefits, pre-regs felt that there was more interaction with patients and preceptors. They appreciated the use of real-life case scenarios and discussions for assessment. The PAs encouraged critical thinking and are comprehensive in defining the scope of work of a pharmacist. The PAs also helped to reflect their real competency level and areas for improvement. The preceptors were supportive of the training and assessment framework. The supervision scale was clearer and more intuitive than the previous rating scale of “Competent” or “Not Competent”. Furthermore, as pre-regs were trained to do the activities commonly performed by pharmacists, preceptors felt that pre-regs would be better prepared for their future roles as registered pharmacists. The training and assessment framework was noted to be better structured compared to the previous framework.

Some pre-regs were concerned about their ability to perform and complete training requirements. The training workload was perceived to be higher, and more preparation work was required to collate learning logs and WBAs. There were also concerns whether they could complete all assignments in a timely manner. Preceptors were concerned with inter-rater variability as WBAs were perceived to be subjective. They found the training framework to be more resource-intensive in terms of manpower and time. There were more documentation requirements. There was confusion on the various WBA tools, types of cases and complexities of cases that could be used for assessment. Preceptors also shared that implementation of the revised framework varied across institutions and the process for document submission to SPC was unclear.

B. Group Interviews

Thirteen interview sessions with 34 participants were conducted between September 2023 and January 2024. Four group interviews were conducted with 15 pre-regs (100%), and six were conducted with 19 preceptors (19/24, 79.2%). Two preceptors and one pre-reg had individual interviews due to conflicting schedules.

C. Theme 1: Validity and Reliability

1) Professional Activities for Direct Patient Care:

Both preceptors and pre-regs agreed that the PAs for direct patient care were clear and appropriate. The six PAs accurately represented the competencies of a Day-1 pharmacist, and no revisions were suggested. However, there were differing views on the following:

a) The core categories under PA 2 (Accurate Supply of Medications) were not applicable to all settings.

“Medicines, quite easy…but the wound management part…Very limited chance, almost sometimes none, depends on the luck, that there will be wound dressing questions.” – Preceptor1

b) There were differing opinions on appropriateness of the passing criteria of Level 3C for PA3 (Educate Patients).

“A 3C and a 4 requires a lot of trust… so I feel that (3C) is a bit too high for PR1”- Preceptor9

“Because I can’t expect them to go into PR2 without a 3C level or so… I did have an expectation of them to be at this level.”- Preceptor7

“I feel…the gradings were quite tough (to achieve)” – Pre-reg13

c) The number of evidence required e.g. 10 case notes for PA1 (Develop and Implement a Care Plan) may not be sufficient. However, preceptors mitigated the concern with WBAs that were formally introduced with the framework.

“I think 10 (SOAP notes) is definitely not enough for me to do a very good evaluation”- Preceptor1

“But we have the new system (WBAs). I’ll argue that you get a better understanding of the student’s actual scope of knowledge…It’s one thing when you have all of the notes on your side and you just craft out the best (written) answer (SOAP), it’s another to be able to test that on the spot to see if they actually know more”- Preceptor6

“For direct patient care.. I feel that because of the new framework, I actually learn more.. like you get to apply what you learn in real life” – Pre-reg5

2) Professional Activities for Indirect Patient Care:

The five PAs for indirect patient care demonstrated poor validity due to the diverse functions pharmacists perform in the industry sector. PAs 7 and 8 were focused on regulatory affairs and restricted some pre-regs’ exposure to other significant industry roles such as marketing and pharmacovigilance. This narrow focus could also limit the number of companies eligible to serve as training sites. Furthermore, PA8 which addressed the roles of the Responsible Person lacked clarity, particularly in its supporting tasks and assessment criteria.

The value proposition of having an indirect patient care rotation as part of registration requirement was raised.

“Are we expecting that all of them would be doing regulatory…to be doing commercial…what is that functional competency we want to train the (pre-regs) on?” – Preceptor18

“…we really need to scope this pharma industry attachment… because if this is the trend moving forward…to scope them as more of an introduction of indirect (patient care)… How indirect patient care actually is important role in your direct patient care”- Preceptor19

“Basically, I feel it’s too streamlined already…like we are all funnelled into the RA role only…although there might be people like me who want to do other stuffs like commercial marketing, medical affairs etc” – Pre-reg10

3) Professional Activity on Developing a Continuous Professional Development (CPD) Plan:

PA6 (Developing a CPD Plan) required greater clarity in terms of its conduct and the template to be used. Several preceptors were unsure how to assess the CPD plans and to guide their pre-regs in developing one. Preceptors also proposed to reduce the number of CPD reviews over the 22-week training period.

“…the CPD, which (my pre-reg) needs to do in the beginning, in the mid and then at the end. It seems to be just repeating only.”- Preceptor10

“ For my student, she doesn’t really know what a CPD entails… she didn’t really know exactly how to fill it in. So when she did fill it in, understandably it was quite general. So she just copied paste…doesn’t really know what she needs to know”- Preceptor1

“Can I ask if CPD is really necessary?” – Pre-reg1

“Actually I am thinking for the final CPD, it can be better formatted…in the sense that we know there is a part on future learning plan and action plan…but it’s already our final week, so we don’t know how applicable it is to us – like we draft a learning plan, but when will we get to execute it” – Pre-reg6

4) Assessments and Supervision Scale:

The supervision scale was found to be intuitive and descriptive as it reflected how independence and supervision is accorded for work. It was preferred over the “Competent or Not Yet Competent” (C/NYC) rating in the previous assessment framework.

“I think C/NYC is like there’s no gray (area)…Most time…it’s not really to the extent that it’s NYC, so yeah, you just end up with a C…I think (the supervision scale) is real…you’ll be managing them like that in the workplace”- Preceptor7

“ I think [the supervision scale] is better …clearer to the PRPs as well…”“I feel my student has more progress …she’s at 3A…Let’s try to progress her to 3B…there was no such articulation [in the previous framework]” – Preceptor1

There was varied interpretation on the “minimum number for WBAs to be completed satisfactorily”. Some preceptors performed the minimum number regardless of assessment outcomes while others aimed to achieve the required passing criteria for all WBAs. There were also concerns about assessor variability affecting the assessment outcomes. Some pre-regs felt that the ratings were not reflective of their actual competencies as the preceptors would just give them the minimum rating for them to pass.

“For the same assessment, one preceptor may grade me as 3B, but to another preceptor, I may be a 3A” – Pre-reg8

“Because no matter how we perform, I feel eventually our preceptor will just pass us by giving us the bare minimum score required”- Pre-reg10

Mini-CEXes and Case-based discussions were conducted in a variety of ways due to a lack of understanding of the purpose of different assessment methods. Multi-source feedback (MSF) contributed to the administrative load for indirect patient care preceptors.

“How do you decide if this is a mini-CEX and this one is a CBD… in the end what I did was like CBD is (for) more complex cases then mini-CEX is (for) easier (cases)?” – Preceptor9

5) Mindset Shift:

Preceptors were unclear of the mindset shift required for prospective decision making that integrated learner attributes – agency, reliability, integrity, humility and capability (ARICH), when using the supervision scale under the revised framework.

“The new framework is actually very content(-based), it doesn’t focus a lot on attitude actually. So if they can get the content done, but their attitude is very poor, I think…we can still pass them actually, but their attitude will be reflected in the comments”- Preceptor12

D. Theme 2: Process

Both preceptors and pre-regs welcomed the change. Pre-regs felt that the revised framework would facilitate a smoother transition to post-course pre-registration training. The preceptors found the revised framework rewarding as it allowed them to be part of the pre-regs’ developmental journey. Pre-regs were viewed as a key success factor for the implementation of the revised framework to be successful and should be empowered to exercise their agency with proper preparation.

The initial implementation process was described as “messy”, and some participants felt “stressful” due to the perceived increase in workload and documentation requirements. Better clarity was needed in terms of the assessment requirements and different types of WBAs to be used.

E. Theme 3: Comfort and Confidence

1) Framework:

Pre-regs were comfortable with the framework and were confident that it would prepare them well for post-course pre-registration training. Preceptors welcomed the change and felt that the framework was learner-centric.

“Compared to the previous (framework)…good change yes…there’s really a lot more feedback…that is now in black and white…For the preceptor, more time-consuming. But I guess if we think in terms of learner-centric kind of role it’s good for the learners.”- Preceptor11

However, they were concerned about scalability due to resourcing concerns.

“Now (phased implementation) is maybe one or two (PRPs on the revised framework per rotation). It’s still fine, but I think really eight at one go…is gonna be pretty overwhelming… And then I think the volume might dilute the effort to give feedback after a while.”- Preceptor13

Preceptors further suggested for cross-learning amongst institutions on framework and WBA implementation, and for more resource materials to be included in the implementation toolkit.

2) Defensibility of Training Decisions:

Preceptors highlighted concerns on the defensibility of training decisions and felt compelled to pass pre-regs due to potential implications related to remediation and its consequences on training capacity and delay in graduation.

“It’s difficult for us not to pass them because it means we need to extend them. Then what are we going to do? Logistically, I think you all know it is very difficult” – Preceptor2

“Once bitten, twice shy. (I document) like everything… if they are going to have issues then I have to bring up the details.” – Preceptor5

IV. DISCUSSION

The revised training and assessment approach uses professional activities (PAs) to frame the assessment, akin to the Entrustable Professional Activities (EPA) approach developed by Cate (2018). In a scoping review conducted by Hennus et al. (2002), the authors found that most programmes used a mix of logics to establish a framework of EPAs. These logics could be categorised into four broad areas: i) service provision, ii) procedures, iii) disease or patient group, and iv) non-EPAs that are unsuitable for summative entrustment decisions but are important as they describe the abilities physicians require to effectively meet healthcare needs (e.g., developing a CPD plan, PA6).

We chose a mixed logic approach to develop our PAs as pharmacists can practise in various settings. The “mixed logic approach” refers to the use of multiple design logics (e.g., task-based, setting-based, developmental) to develop professional activities. We link this to Hennus et al.’s (2022) framework on EPA design and align it with the iterative, participatory principles of action research (Plan-Act-Observe-Reflect). In Singapore, slightly more than half (approximately 55%) of our locally registered pharmacists work in patient care areas (tertiary hospitals, polyclinics, and retail pharmacies), while the remaining work in indirect patient care areas such as pharmaceutical industries and regulatory bodies (data provided by SPC). The Committee thus envisioned a training system whereby pharmacists from both settings could collaborate and co-develop outcomes for a holistic training programme for our local graduates. For harmonisation across all training sites, PAs for indirect patient care areas were developed. As not all professional activities fit the descriptors of an EPA as described by Cate and Taylor (2020), we have chosen to describe them as professional activities instead of EPAs. PAs 1 to 6 were adapted from those used for new pharmacy graduates in USA (Haines et al., 2017) and the general level training of junior pharmacists in a local academic medical centre since 2019, whereas PAs 7 to 10 were developed by local domain experts from the pharmaceutical industry and regulatory authority.

The results of our study showed that PAs for direct patient care were valid and mostly pegged appropriately to entry to practice level pharmacists. There were concerns about the supervision level for PA3 which some preceptors felt that it was pegged beyond an entry level pharmacist. Preceptors felt that it would be difficult to achieve the suggested level within a short duration of 11 weeks especially when this is the first pre-licensing assessment in their undergraduate days. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no PAs developed for pharmacists working in pharmaceutical companies. It was challenging to develop PAs due to the diverse roles pharmacists can play in the indirect patient care areas. Hence, preceptors felt that PAs 7 and 8 were too restrictive. Furthermore, the value preposition of having an indirect patient care rotation was unclear. Henceforth, there were varied opinions on what would constitute indirect patient care PAs. As SPC has not implemented CPD yet, PA6 will need to be refined further for clarity.

As WBAs were not widely used in all participating training institutions, there were varying comfort levels and understanding amongst preceptors and pre-regs in using mini-CEX and CBD for assessments. Resourcing for manpower, contact time with pre-regs and documentation were cited as key concerns among the preceptors. Similar concerns were raised by Massie and Ali (2015), who suggested approaches to alleviate these issues, including clarifying the purpose of WBA, mandatory training to reduce inter-rater variability and increasing trainees’ engagement with the WBA tools, building training time into preceptors’ responsibilities, as well as improving accessibility to WBA forms with tablet/smartphone applications (Massie & Ali, 2015; So et al., 2024).

The pre-regs’ concerns about inter-rater variability were valid concerns as it may impact the reliability of the revised training and assessment framework. This was subsequently mitigated with additional training sessions for preceptors and several preceptor townhalls to address queries and concerns. Further Phase 2 research is required to understand the preceptors’ concerns with ‘failure-to-fail’ and ensuring defensibility of their decisions as these may potentially compromise the quality of pre-regs who exit the programme and contribute to unpleasant training experience for preceptors through an onerous documentation workload.

The initial implementation process was highlighted as “messy”. Submission of training documents to SPC was done manually as the online registration system was not updated for the revised framework. Moving forward, the registration system will be renewed to support the submission of the training documents in a seamless manner. To mitigate the initial confusion and understanding of PA requirements, SPC will collaborate with NUS to conduct detailed briefing sessions for pre-regs in the subsequent phases of implementation. This is to better enable the students to drive their own learning during rotations, as highlighted by preceptors.

Overall, preceptors and PRPs welcomed the change and are supportive of the revised framework. Many felt that the change was a clearer reflection of the daily work as a pharmacist. The Committee had reviewed the key study findings and proposed the following recommendations and action plans which were implemented prior to Phase 2:

- The Indirect Patient Care PAs were further refined for clarity and to broaden the scope beyond regulatory affairs.

- The number of CPD plan reviews for PR1 were reduced from six to four.

- The number of documents for SPC submission was streamlined to ease administrative burden.

- The toolkit was updated to reflect changes made and included frequently asked questions, providing both pre-regs and preceptors with comprehensive information.

- Emphasis on WBAs was increased at the national faculty development workshops that were conducted to upskill existing preceptors.

- SPC worked with NUS to conduct more in-depth briefing sessions prior to the start of their PR1 training, to better prepare pre-regs to navigate the training requirements.

- SPC established a Pre-Registration Training Advisory Committee to better support preceptors in the implementation of the framework.

- SPC will commence an annual faculty development event for preceptors to share best-practices.

A. Limitation

This study is limited to the context settings of the participating PR1 rotation sites and has a small sample size, thereby limiting the generalisability of findings.

V. CONCLUSION

A robust training and assessment framework, incorporating meaningful placement experiences, is essential for pre-regs to develop and demonstrate their competence for professional practise. This study shares our experience of implementing PAs in pre-registration training across both direct and indirect care settings, and how action research guided our phased framework implementation. The findings may benefit other international pharmacy institutions implementing EPA frameworks. As this framework is newly established, longitudinal monitoring of PRPs’ post-training performance will be necessary to validate its effectiveness in developing the required workforce and to inform further programme refinements.

Notes on Contributors

Sei Keng Koh was involved in the conceptualisation of this paper, writing and revision.

Li Wen Loo was involved in the conceptualisation of this paper, interviewing, data analysis, writing and revision.

Zhining Goh was involved in the conceptualisation of this paper, interviewing, data analysis and revision of manuscript.

Dujeepa D. Samarasekera was involved in the design of the research methodology and in the revision of the manuscript.

Carolyn Ching Ching Ho was involved in the revision of manuscript.

Paul John Gallanger was involved in the revision of the manuscript.

Wai Keung Chui was involved in the revision of the manuscript.

Camilla Ming Lee Wong was involved in the revision of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of the Singapore Health Services (CIRB ref: 2023/2393) and the National University of Singapore.

Data Availability

No data was given to share transcript data and analysis.

Acknowledgement

We thank the Singapore Pharmacy Council, the Pre-Registration Training Standards Committee, the preceptors and pre-registration pharmacists for their support in this research study.

We thank Mr Richmond Ng from the Singapore Pharmacy Council for his assistance with the data extraction.

Funding

There is no funding support for this study.

Declaration of Interest

All authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

Abeyaratne, C., & Galbraith, K. (2023). A review of entrustable professional activities in pharmacy education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 87(3), ajpe8871. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe8872

Abeyaratne, C., & Galbraith, K. (2024). Implementation and evaluation of entrustable professional activities for a pharmacy intern training program in Australia. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 88(12), 101308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpe.2024.101308

Castillo-Montoya, M. (2016). Preparing for interview research: The interview protocol refinement framework. The Qualitative Report, 21(5), 811–831. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2337

Cate, O. T. (2005). Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Medical Education, 39(12), 1176–1177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02341.x

Cate, O. T. (2018). A primer on entrustable professional activities. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 30(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2018.76

Cate, O. T., & Taylor, D. R. (2020). The recommended description of an entrustable professional activity: AMEE Guide No. 140. Medical Teacher, 43(10), 1106–1114. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2020.1838465

Dikko, M. (2016). Establishing construct validity and reliability: Pilot testing of a qualitative interview for research in Takaful (Islamic Insurance). The Qualitative Report, 21(3), 521–528. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2243

George, T. (2024). What is action research? Definitions and examples. Retrieved February 9, 2025, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/action-research/

Goh, D. L., Samarasekera, D. D., & Jacobs, J. L. (2015). Implementing entrustable professional activities at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine Singapore undergraduate medical education program. South‐East Asian Journal of Medical Education, 9(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.4038/seajme.v9i1.90

Haines, S. T., Pittenger, A. L., Stolte, S. K., Plaza, C. M., Gleason, B. L., Kantorovich, A., McCollum, M., Trujillo, J. M., Copeland, D. A., Lacroix, M. M., Masuda, Q. N., Mbi, P., Medina, M. S., & Miller, S. M. (2017). Core entrustable professional activities for new pharmacy graduates. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 81(1), S2. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe811s2

Hennus, M. P., Van Dam, M., Gauthier, S., Taylor, D. R., & Cate, O. T. (2022). The logic behind entrustable professional activity frameworks: A scoping review of the literature. Medical Education, 56(9), 881–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14806

Lau, S. T., Ang, E., Samarasekera, D. D., & Shorey, S. (2020). Development of undergraduate nursing entrustable professional activities to enhance clinical care and practice. Nurse Education Today, 87, 104347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104347

Massie, J., & Ali, J. M. (2015). Workplace-based assessment: A review of user perceptions and strategies to address the identified shortcomings. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 21(2), 455–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-015-9614-0

Ministry of Health, Chief Pharmacist’s Office. (2024). Development Framework for Pharmacists (DFP).

Richardson, C. L. (2024). Entrustable professional activities: A new approach to supervising trainee pharmacists on clinical placements. Retrieved February 9, 2025, from https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/entrustable-professional-activities-a-new-approach-to-supervising-trainee-pharmacists-on-clinical-placements

Singapore Pharmacy Council. (2010, March). Competency standards for Singapore pharmacists.

So, H., Choi, Y., Chan, P., Chan, A. K., Ng, G. W., & Wong, G. K. (2024). Workplace-based assessments: What, why, and how to implement? Hong Kong Medical Journal, 30(3), 250–254. https://doi.org/10.12809/hkmj2311361

Zainuldin, R., & Tan, H. Y. (2023a). Entrustable professional activities developed for allied health entry-level programs across a national level training standards framework in Singapore. PubMed, 52(2), 104–112. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37269028

Zainuldin, R., & Tan, H. S. K. (2023b). Entrustable professional activities implementation in undergraduate allied health therapy programs. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 9(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.29060/taps.2024-9-1/sc2997

Zhou, W., Poh, C. L., Chan, H. L., & Shorey, S. (2022). Development of entrustable professional activities for advanced practice nurses education. Nurse Education Today, 116, 105462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105462

*Sei Keng Koh

Division of Pharmacy, Singapore General Hospital

Level 9, SingHealth Tower

10 Hospital Blvd, Singapore 168582

+65-81251901

Email: koh.sei.keng@sgh.com.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.