Impact on wellness and adaptation by stakeholders in challenging time: A sequential explanatory mix-method study

Submitted: 16 August 2024

Accepted: 23 December 2024

Published online: 1 July, TAPS 2025, 10(3), 49-57

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-3/OA3495

Shuh Shing Lee1, Shefaly Shorey2, Tang Ching Lau3 & Dujeepa D. Samarasekera1

1Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Alice Lee Centre for Nursing Studies, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 3Dean’s Office, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Numerous studies have been conducted on COVID-19, with the majority focusing on interventions involving students and teachers. However, limited research has delved into the pandemic’s impact on the wellness of various stakeholders and how they have adapted to the challenges it presented. This study aims to fill this gap by exploring these neglected areas.

Methods: This study employs a sequential mixed-method approach to study these areas. The quantitative data collection was carried out using a combination of validated surveys (ranging between 63-88 items) for students, faculty and administrators. Subsequently, qualitative data collection was gathered via semi-structured interview using a convenient sampling method.

Results: Seventeen faculty, 18 administrators and 369 students responded to the survey. The quantitative data indicated faculty (teachers) exhibited the lowest stress levels and the highest resilience during the pandemic. In comparison, administrators and students experienced moderate levels of stress, with students scoring slightly higher on the stress level. The themes that emerged from the qualitative data were personal endurance, emotional reaction, cognitive-behavioural reaction and social support.

Conclusion: Our study highlighted that, apart from personal endurance, the tension arises from emotional and cognitive-behavioural responses of students, teachers, and administrators can be mitigated based on the presence or absence of support mechanisms.

Keywords: Wellbeing, Change, Stakeholders, Educational Environment, Culture

Practice Highlights

- Students experienced the highest stress levels compared to administrators and teachers.

- However, students and administrators demonstrated resilience, bouncing back quickly after challenging times.

- Students and administrators tolerated for uncertainty and displayed cognitive flexibility to enable them to adapt and seek opportunities.

- Teachers and administrators initially experienced negative emotions, but their emotional resilience facilitated quick recovery.

- Coming from a culture emphasising collectivism, the sense of belonging and social connection served as a protective factor against psychological distress.

I. INTRODUCTION

The foundation of any education system rests upon the harmonious collaboration of three essential elements: teachers, students, and administrators. Each of these components play a vital role in ensuring the smooth functioning of the educational ecosystem and this symbiotic relationship becomes even more evident during challenging times, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Together, they navigated the complexities of remote learning, ensuring that the pursuit of knowledge remained uninterrupted. In essence, it is the collaborative synergy of these three integral components that propels the educational journey forward. The strength of an education system lies in the seamless interplay of these elements, fostering a holistic and empowering learning experience for all.

Nevertheless, numerous studies have studied the impact of pandemic such as SARS, COVID-19, with a predominant focus on students and teachers. A significant portion of these studies, approximately 50%, has highlighted the insights and innovations from health professions educators in response to the pandemic, particularly at the undergraduate level (Daniel et al., 2021; Eva & Anderson, 2020; Gordon et al., 2020). The majority of these investigations have primarily collected data on student reactions, satisfaction levels, shifts in attitudes, and changes in knowledge and skills. The review conducted by Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) revealed that almost half of the studies centred on the transition from traditional in-person teaching to online education, only a meagre 6% of the research primarily focused on aspects related to well-being, mental health, or learner support (Daniel et al., 2021). Amid the widespread concern about the well-being of individuals during the pandemic, much attention has been given to medical students (Jia et al., 2022; Paz et al., 2022; Wilcha, 2020) and frontline healthcare workers (Danet, 2021; Muller et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2022) in the published articles. The reactions of teachers and administrators to the changes brought about by the pandemic, and how these changes have impacted their well-being, have been largely overlooked in the existing literature.

Hence, the principal objective of this research is to investigate the impact of the initiatives implemented during the pandemic on the well-being of students, teachers, and administrators. This study aims to explore how these key stakeholders reacted and adapted to the changes, shedding light on a vital aspect that has been underrepresented in the current body of literature.

II. METHODS

We employed a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design to assess the adaptation and impact of the pandemic on the well-being of administrators, teachers, and students within the specific context of the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) at the National University of Singapore. This design involved collecting and analysing both quantitative and qualitative data in two consecutive phases within a single study. In the quantitative phase, data were gathered through a comprehensive survey/questionnaire, allowing us to capture a broad spectrum of responses from the participants. Subsequently, in the qualitative phase, we employed the phenomenological approach, conducting in-depth interviews with participants representing various categories. Phenomenology, as an approach in qualitative research, enables us to delve deeply into the shared experiences within a specific group. The primary objective of this approach is to develop a detailed description of the nature of the phenomenon under investigation (Creswell, 2013). The details of this methodological approach are elaborated in the subsequent sections.

A. Phase I Quantitative Data Collection

The quantitative data collection was carried out using a survey. The survey was adapted from Landis’s and Bradley’s (2003) work on The Impact of the 2003 SARS Outbreak on Medical Students at the University of Toronto, The Brief Resilience Scale (Smith et al., 2008), Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983) and Teachers’/Students’ Self-Efficacy towards Technology Integration (Kiili et al., 2016). Table 1 shows the sections of the surveys for administrators, teachers and students.

|

Section |

Items in each section |

||

|

Student |

Teacher |

Administrator |

|

|

A: Demographic Information |

5 |

8 |

7 |

|

B: The psychological impact of COVID-19 |

7 |

||

|

C: Perception of medical students on the restriction of clinical activities and the impact of COVID-19 on their medical/nursing education |

15 (13 5-point likert scale items & 2 open-ended questions) |

2 (open-ended questions) |

2 (open-ended questions) |

|

D: Perceived quality of information received by respondents about COVID-19 from specific groups |

8 |

||

|

E: The source and level of psycho-social support that medical students rely on during the COVID-19 outbreak |

26 |

19 |

|

|

F: Brief Resilience Scale |

6 |

||

|

G: Perceived Stress Scale |

10 |

||

|

H: Teachers’/Students’ Self-Efficacy towards Technology Integration |

11 |

4 |

|

|

Total Items |

88 |

71 |

63 |

Table 1. Sections of the Surveys for Administrators, Teachers and Students

The survey was validated by 10 medical educators from various departments (Paediatrics, Surgery, Centre for Medical Education, Nursing). After the validation, the survey was administered to medical (Year 1 – 5) and nursing (Year 1 – 4) students, administrators and faculty members in Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine and Alice Lee Centre for Nursing Studies using convenient sampling. It took about 20-30 minutes to complete the survey and the data was collected between Jan – June 2021.

B. Phase II Qualitative Data Collection

The qualitative data collection was gathered via semi-structured interview. The interview was conducted for about 60-90 minutes among the medical/nursing students, administrators and faculty members (teachers). Followed up from the data collected from the quantitative data, the questions were revolved around teaching and learning, content, assessment, policies, guidelines, communication, environment (safety)/support and wellness.

From July 2021 – Nov 2022, we used convenient sampling method to recruit of students, administrators and faculty members. The interviews were carried out by 2 trained interviewers with no power relationship with the interviewees. Interviews were carried out after getting consent from the volunteer interviewees. All digital audio recordings made during the interviews were transcribed and member-checked with the interviewees to ensure transparency and trustworthiness of the data.

Data collection ceased when the data reached saturation stage.

C. Data Analysis

The quantitative data was analysed using descriptive statistics (such as mean, frequency and percentage) using Microsoft Excel for the data collected from students, administrators and teachers.

The interviews were thematically analysed by 2 researchers in the team. The two researchers coded the transcripts independently and came together to resolve any discrepancy or disagreement on the coding. Subsequently, they continued to code and form categories and eventually themes. There were multiple discussions that took place among the researchers and the team before the themes were crystalised.

III. RESULTS

A. Phase I Quantitative Data

The demographic information was illustrated in Table 2. Majority of the participants were not quarantined during the pandemic and more than 80% of them did not have a family member tested positive for COVID when this study was conducted. The teachers from the school of medicine were mainly from Family Medicine, Paediatrics, Physiology, Pathology, Public Health, Medicine, Anatomy and Anaesthesia departments. They are educators for postgraduate and undergraduate students. As for administrators, their roles in the departments are educational related such as instructional design, learning analytics, planning and execution of education, managing project and training.

|

|

|

|

Teachers |

Administrators |

Students |

|||

|

0 |

Finished |

Completed |

17 |

65.4% |

18 |

54.5% |

369 |

73.8% |

|

Did not complete |

9 |

34.6% |

15 |

45.5% |

131 |

26.2% |

||

|

Total Responses |

26 |

33 |

|

500 |

|

|||

|

1 |

Faculty |

Medicine |

12 |

70.6% |

16 |

88.9% |

305 |

83.0% |

|

Nursing |

5 |

29.4% |

2 |

11.1% |

64 |

17.0% |

||

|

2 |

Gender |

Male |

6 |

35.3% |

3 |

16.7% |

140 |

37.9% |

|

Female |

11 |

64.7% |

15 |

83.3% |

229 |

62.1% |

||

|

6 |

Living arrangement |

Alone |

1 |

5.9% |

1 |

5.6% |

17 |

4.6% |

|

With Parents |

2 |

11.8% |

7 |

38.9% |

338 |

91.6% |

||

|

With Partners (married, common-law, etc.) |

14 |

82.4% |

9 |

50.0% |

1 |

0.3% |

||

|

With Room-mates |

0 |

0.0% |

1 |

5.6% |

13 |

3.5% |

||

|

7 |

Status during COVID-19 Outbreak |

Non-Quarantined |

17 |

100.0% |

18 |

100.0% |

355 |

96.2% |

|

Quarantined |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

7 |

1.9% |

||

|

Stay-Home-Notice (SHN) |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

7 |

1.9% |

||

|

8 |

I have family member(s), relative or friend(s) who tested positive for COVID-19 |

Yes |

2 |

11.8% |

1 |

5.6% |

29 |

7.9% |

|

No |

15 |

88.2% |

17 |

94.4% |

340 |

92.1% |

||

Table 2. Demographic Information of the Respondents

For each section, the summary was illustrated in Table 3. The mean for different sections was quite close for the 3 groups. Likewise, the items that were scored low and high were quite similar for all the sections. For example, Section B The psychological impact of COVID-19, The sleep quality and concentration in all three groups were not affected by the pandemic, but they are more worries about their family members contracted with COVID-19.

|

Section |

Administrator |

Teacher |

Student |

|

B: The psychological impact of COVID-19 (7 items) |

Mean ranging between 2.39-3.67 |

Mean ranging between 1.71 – 3.29 |

Mean ranging between 2.14 – 3.85 |

|

C: Perception of medical students on the restriction of clinical activities and the impact of COVID-19 on their medical/nursing education (15 items) |

Mean ranging between 1.77 – 3.78 |

Not relevant |

|

|

D: Perceived quality of information received by respondents about COVID-19 from specific groups |

Mean ranging between 3.33 – 4.17 |

Mean ranging between 3.47 – 4.19 |

Mean ranging between 3.17 – 4.14

|

|

E: The source and level of psycho-social support that medical students rely on during the COVID-19 outbreak |

Mean ranging between 2.78 – 4.11 |

Mean ranging between 2.47 – 4.47 |

Mean ranging between 2.65 – 4.36

|

|

F: Brief Resilience Scale |

Mean 3.4 |

Mean 4.01 |

Mean 3.3 |

|

G: Perceived Stress Scale |

Mean: 16.6 (Moderately stress) |

Mean 11.7 (Low stress) |

Mean 18.7 (Moderately stress) |

|

H: Teachers’/Students’ Self-Efficacy towards Technology Integration |

Mean ranging between 3.83-4.06 |

Mean ranging between 3.47 – 4.12 |

Mean ranging between 3.68 – 4.22 |

Table 3. Summary of the Mean for Different Sections for the 3 Groups

During the pandemic, students expressed significant concerns about the adequacy of their training, particularly due to reduced patient contact, raising apprehensions about their preparedness for exams. This concern will be elaborated upon in the qualitative data section, shedding light on the depth of their worries. All three groups shared the view that information originating from the government and hospitals was the most reliable, with friends and family scoring the lowest mean among all sources. Despite this, the participants unanimously agreed that the support from friends and family, in terms of both source and level of assistance, was the most substantial. Conversely, organisational support from entities such as the University Wellness Centre, Dean’s office, community, and social media was perceived as unreliable and lacking during the pandemic.

Furthermore, our observations revealed that teachers exhibited the lowest stress levels and the highest resilience during the pandemic, showcasing their ability to cope effectively. In comparison, administrators and students experienced moderate levels of stress, with students scoring slightly higher on the Perceived Stress Scale. Although students acknowledged challenges, as indicated by their agreement with statements such as “I have a hard time making it through stressful events” (mean: 2.93), they also exhibited resilience, agreeing with the statement “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times” (mean: 3.76). Additionally, concerning self-efficacy towards technology integration, students reported the highest mean score, indicating confidence in their ability to navigate various Internet applications. While teachers felt competent in using technology for teaching and learning, their confidence wavered when it came to resolving technical issues, as reflected in their mean score of 3.47. This nuanced understanding underscores the complex interplay of stress, resilience, and technological proficiency among the different groups during the challenging circumstances of the pandemic.

B. Phase II Qualitative Data

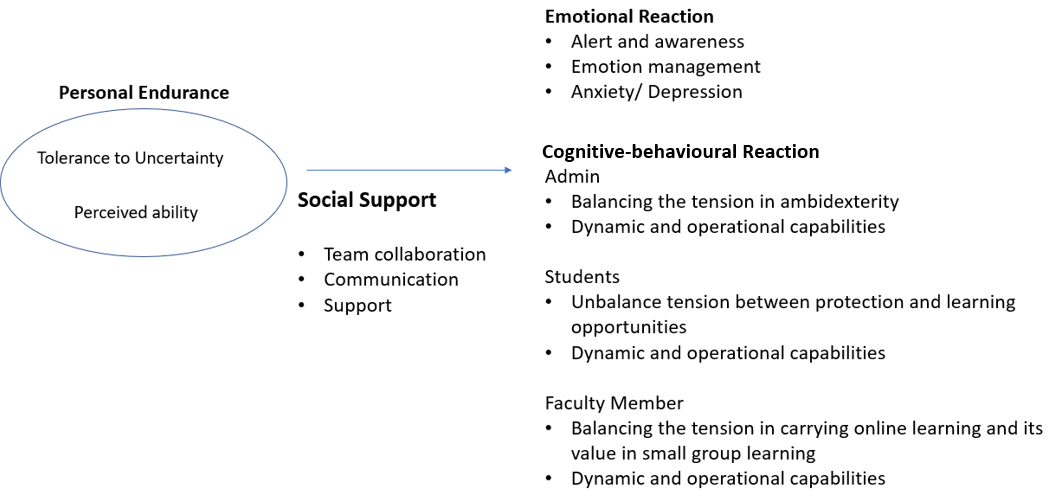

As for the qualitative data collection, we have recruited 7 administrators, 17 teachers (12 from Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine and 5 from Alice Lee Centre for Nursing Studies) and 9 undergraduate students (6 from Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine and 3 from Alice Lee Centre for Nursing Studies). The themes and subthemes that emerged were depicted in the Figure 1.

Figure 1. Themes and Subthemes of the Qualitative Data

1) Theme 1: Personal Endurance

Personal endurance depends on perceived ability and tolerance to uncertainty. For administrators, they felt that it was quite stressful and frustrated during the pandemic as the situation was unclear. However, they were able to manage and there was a sense of relief after they had gone through the critical phase.

“It was very intense, stressful but looking back now, it is not that bad. We have gone through the worse” (Admin 5)

While administrators’ contribution to the education system is crucial, some of the administrators perceived their contribution was minor as compared to medical front liner.

“We are not front liner, our contribution is limited.” (Admin 3)

Although the situation was stressful in the beginning, we noticed a positive endurance among the teachers and perceived the pandemic as an opportunity instead of a threat.

“Overall, I think the predominant mood was of a challenge that needs to be overcome and that brought a certain amount of excitement.” (Teacher 7)

On the other hand, the students felt that they were being too protected and perceived themselves as having the ability to manage the situation themselves.

“I understood that they wanted to protect us but I felt that eventually, they can’t protect us anymore” (Student 3)

The students also perceived that the teachers lacked ability in using technology in teaching and learning especially in remote learning.

“A lot of professors are not familiar with the technology.” (Student 5)

2) Theme 2: Emotional Reaction

There were a lot of negative emotions illustrated by the students, administrators and teachers due to various reasons. Students were worried, frustrated and anxious that they may not learn since the contact with the patients was less during the pandemic. Too much protection from the school and the system put in place has heightened these negative emotions.

“We feel quite unconfident because we feel we have not seen enough patients”/ “..fear that we are not as good as the previous batch” (Students 1 & 2)

Administrators were frustrated mainly because they need to manage the family and work at the same time when working from home system was implemented. However, some of them shared that they are able to regulate and get used to the situation after a while.

“Everybody was under pressure at that time…while I have to juggling with work, my kids were at home because school close.” (Admin 4)

“I usually regulate my own emotion.” (Admin 7)

While there were some positive emotions state in Theme 1 for teachers, they did feel stressful in the early stage of the pandemic due to the change of the approaches in teaching and learning and they are unsure of the outcomes when the teaching was entirely online.

“…stressful in the beginning… I even have nightmares…dreaming students get lost in the virtual room.” (Teacher 17)

“It was a bit stressful in the beginning because you did not know how is going to turn out…” (Teacher 5)

3) Theme 3: Cognitive-Behavioural Reaction

Amidst the challenges posed by the pandemic, administrators, students, and teachers made concerted efforts to adapt their cognition and behavior in response to various initiatives, including social distancing measures, reduced patient contact, and a shift to virtual teaching environments. Throughout this period, interviewees shared both positive and negative reactions to these changes.

Administrators and teachers found themselves navigating the delicate balance between the need to innovate and the need to maintain productivity (ambidexterity). Administrators, in particular, faced the challenge of fostering creativity in coordinating and delivering the curriculum, which involved tasks such as timetabling, resource management, and providing IT support for online learning. These adjustments were made within a short timeframe, reflecting their resilience and adaptability. However, amid these innovative efforts, administrators were also keen on upholding the quality of their work, highlighting the complexity of their role in managing these rapid changes.

“We have to deliver in a short time but also the content has to be rigorous” (Administrator 3)

Similarly, teachers tried to be creative in an online teaching environment and ensure the student learned at the same time especially in small group teaching. However, they find it challenging.

“…there is an urgency to find a way around this small group teaching…we kind of lose the whole power of collaboration.” (Teacher 5)

There is also a tension arose among the students for being too protected by the school and compromised with their learning as shared in the quotes below. This was repeatedly mentioned by the students, and they felt they have to face the situation eventually.

“I am not very interested in surgery, but this is like once in a lifetime and after I go out of medical school I won’t have the chance to see surgery” (Students 3)

“There’s a culture… in the society in general…protect my child from COVID. But once day we are going to deal with COVID” (Students 6)

Notwithstanding the aforementioned tensions, it’s worth noting that administrators, students, and teachers exhibited remarkable innovativeness and adaptability during the pandemic. All three groups demonstrated evidence of both Operational Capabilities, which encompass the efficient and effective use of resources, and Dynamic Capabilities, which involve the continuous development of competencies to align with the evolving environment.

With the predominant shift in communication from face-to-face to virtual platforms, administrators found themselves assuming the role of intermediaries responsible for conveying information to various stakeholders. In this new virtual setting, where body language cues were less apparent, administrators recognised the need to be more attuned and sensitive to subtle nuances in communication compared to traditional face-to-face interactions. This adaptation reflected their ability to pivot and operate effectively within the changing landscape of remote communication.

“We play the middleman role because we have to speak administrative language to certain people and be sensitive when communicate with faculty members” (Admin 3)

“We have to start thinking about (what kind of information needed) before the faculty member even ask those questions” (Admin 7)

Teachers utilised different resources to innovate in their teaching as well as learning from different others.

“I break it up my lectures into smaller bits and disperse it with PollEverywhere” (Teacher 5)

“We formed a group we called a brown bag meeting – basically we meet at lunchtime with technologically savvy administrators to introduce to the staff on how to make online learning more interactive.” (Teacher 10)

Likewise, since there was less patient contact time, students tried to make use of their time for other learning sessions.

“Since there’s little time in the hospital, I had read up a lot” (Students 1)

“It allows us to have some processing time and have time to consolidate our knowledge” (Students 5)

4) Theme 4: Social Support Mechanism

Social support mechanism has been mentioned by the 3 groups as one of the prominent mechanisms in adapting the changes during pandemic. It includes transparent communication, team collaboration and support from various stakeholders. For example, administrators shared that they all came together and supported each other during the hard times.

“All different teams come together, I think that was very precious” (Administrator 2)

Students sought seniors’ help to provide additional sessions to compensate their learning.

“What my group would do is we call our seniors to give us extra tutorials” (Student 2)

However, there was also lack of support mechanism brought up by the teachers which led to negative emotion (such as frustration).

“Educational technology team are overworked…if the school would really want to be the best or world class, I think we need a very good support from the IT.” (Teacher 9)

IV. DISCUSSION

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on both our educational systems and personal lives has been profound. This unprecedented disruption has been keenly observed by various stakeholders, including administrators, teachers, many of whom were also frontline workers, and students in medical schools. Swift adaptation to the ever-changing situation became imperative, particularly in response to the government’s new guidelines. The abrupt alterations in social interactions and extracurricular activities routines compelled a shift towards a heightened emphasis on family life, accompanied by the necessity to work and learn from home due to lockdown measures. These changes had profound physical and psychological effects on our lives.

Our study revealed that students experienced the highest stress levels compared to administrators and teachers, a finding consistent with previous research indicating that medical students often have higher baseline anxiety than their peers studying other disciplines (Dyrbye et al., 2006; Lasheras et al., 2020). Qualitative data highlighted that students’ stress levels were primarily attributed to the lack of patient contact and inadequate training, potentially impacting their future practice. Additionally, students expressed feelings overly protected due to initiatives like stay-at-home learning. The altered learning environment, combined with a lack of guidance on learning strategies and interpersonal relationships, left students vulnerable to intense emotional fluctuations and strained family relationships (Zhang et al., 2020). Similarly, for administrators, the shift to remote work and social isolation policies posed challenges in balancing work and family responsibilities, as evident from their qualitative comments.

However, students and administrators demonstrated resilience, bouncing back quickly after challenging times. According to Del Carmen Pérez Fuentes et al.’s (2020) Adaptability to Change framework, a sense of control, tolerance for uncertainty, and cognitive flexibility are crucial in coping with adverse situations. Despite feeling anxious and frustrated due to the inability to control the study-from-home or working-from-home policy, student and administrator tolerated for uncertainty and display cognitive flexibility to enable them to adapt and seek opportunities. Emotional resilience, the ability to generate positive emotions and recover swiftly from negative emotional experiences, played a pivotal role in psychological resilience (Zhang et al., 2020). This emotional resilience led to diverse emotional responses, influencing the cognitive processing of emotional information. Teachers and administrators initially experienced negative emotions, but their emotional resilience facilitated quick recovery, evident from their transcripts.

Emotional and cognitive-behavioural responses were further shaped by social support mechanisms within peer groups, colleagues, organisational leaders, and the government. While studies have shown that social media can heighten anxiety due to misinformation and distressing news (Gao et al., 2020), our research indicated that students, teachers, and administrators placed significant trust in information provided by the government and institutions. This trust in government intentions and capabilities fosters adherence to health regulations, essential in crisis management (Siegrist & Zingg, 2014).

Coming from a culture emphasising collectivism, our society values interdependence and family connections highly. This sense of belonging and social connection served as a protective factor against psychological distress, aligning with previous research findings (Xiao, 2021; Yu et al., 2020) . Conversely, a lack of social support within a collectivist culture, as reported by teachers and students, contributed to psychological distress. Our qualitative and quantitative data in this study support this observation, emphasising the significance of social support structures in mitigating the adverse effects of challenging circumstances. The importance of fostering a supportive environment, both within institutions and at a societal level, cannot be overstated in times of crisis.

V. LIMITATIONS

This study has some potential limitations. The study was carried out in a single medical school; hence, the results can only be transferable to the same context. The number of respondents was quite small (especially for nursing respondents) despite multiple reminders sent to the various groups. Therefore, they may not be representative of the entire student, teachers and administrator’s population. Third, the survey was a self-reported survey and may have inherent biases while answering the questions. While rigor is more challenging to achieve in qualitative data collection and analysis, the researchers adhere to the trustworthiness principles as much as possible in analysing and presenting the results in this paper.

VI. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, achieving wellness during a pandemic is indeed possible, but it hinges not only on the resources that organisations and governments can marshal but also on individual resilience in navigating uncertainty, cultural factors, trust, and support systems. Our study highlights the importance of familial and peer connections within our cultural context, underscoring how these bonds facilitate adaptation and innovation amid the challenges posed by the pandemic. The emotional and cognitive-behavioural responses of students, teachers, and administrators are depending on their personal endurance. However, the tension that arises in these individuals can be mitigated or exacerbated based on the presence or absence of adequate support mechanisms. Sufficient support can act as a buffer, helping individuals cope effectively with the challenges they face. Conversely, insufficient support can exacerbate stress and strain, hindering their ability to adapt and respond positively to the situation at hand.

Therefore, fostering a strong support network, both within organisations and communities, is crucial. This support not only alleviates the immediate challenges faced by individuals but also empowers them to build emotional resilience, enabling them to navigate uncertainties and adversities with greater ease. In this way, the collective endurance of individuals, coupled with robust support systems, becomes the cornerstone of achieving wellness and fostering positive responses in the face of a pandemic.

Notes on Contributors

DDS developed the research idea and design with SSL, SR & LTC. The data collection was performed by SSL. The data were analysed by SSL & DDS. DDS, SSL, SR & LTC performed the data interpretation. DDS, SSL & SR wrote the article with revision by LTC. All the authors read and agreed with the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was sought from the National University of Singapore (NUS) Institutional Review Board (NUS-IRB-2020-216). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available as the participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to Jillian Yeo and Lilusha Kaludewa for helping in data collection and analysis.

Funding

No funding is available for this research.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report that there are no conflict of interests to declare.

References

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

Creswell, J. W. (2013, January 1). Steps in conducting a scholarly mixed methods study [Slide show]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1047&context=dberspeakers

Danet, A. D. (2021). Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in Western frontline healthcare professionals. A systematic review. Medicina Clínica (English Edition), 156(9), 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcle.2020.11.003

Daniel, M., Gordon, M., Patricio, M., Hider, A., Pawlik, C., Bhagdev, R., Ahmad, S., Alston, S., Park, S., Pawlikowska, T., Rees, E., Doyle, A. J., Pammi, M., Thammasitboon, S., Haas, M., Peterson, W., Lew, M., Khamees, D., Spadafore, M., . . . Stojan, J. (2021). An update on developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A BEME scoping review: BEME guide no. 64. Medical Teacher, 43(3), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2020.1864310

Del Carmen Pérez-Fuentes, M., Del Mar Molero Jurado, M., Martínez, Á. M., Fernández-Martínez, E., Valenzuela, R. F., Herrera-Peco, I., Jiménez-Rodríguez, D., Mateo, I. M., García, A. S., Del Mar Simón Márquez, M., & Linares, J. J. G. (2020). Design and validation of the adaptation to change questionnaire: New realities in times of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155612

Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2006). Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Academic Medicine, 81(4), 354–373. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009

Eva, K. W., & Anderson, M. B. (2020). Medical education adaptations: Really good stuff for educational transition during a pandemic. Medical Education, 54(6), 494. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14172

Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y., Chen, S., Wang, Y., Fu, H., & Dai, J. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE, 15(4), Article e0231924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924

Gordon, M., Patricio, M., Horne, L., Muston, A., Alston, S. R., Pammi, M., Thammasitboon, S., Park, S., Pawlikowska, T., Rees, E. L., Doyle, A. J., & Daniel, M. (2020). Developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid BEME systematic review: BEME guide no. 63. Medical Teacher, 42(11), 1202–1215. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2020.1807484

Jia, Q., Qu, Y., Sun, H., Huo, H., Yin, H., & You, D. (2022). Mental health among medical students during COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 846789. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.846789

Kiili, C., Kauppinen, M., Coiro, J., & Utriainen, J. (2016). Measuring and supporting pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy towards computers, teaching, and technology integration. The Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 24(4), 443–469. https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/123456789/53087/1/kiilikauppinencoiroutriainen.pdf

Lasheras, I., Gracia-García, P., Lipnicki, D., Bueno-Notivol, J., López-Antón, R., De La Cámara, C., Lobo, A., & Santabárbara, J. (2020). Prevalence of anxiety in medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186603

Mark, L., & John, B. (2003). The impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak on medical students at the University of Toronto. University of Toronto Medical Journal, 82, 158–164. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:59193656

Muller, A. E., Hafstad, E. V., Himmels, J. P. W., Smedslund, G., Flottorp, S., Stensland, S. Ø., Stroobants, S., Van De Velde, S., & Vist, G. E. (2020). The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: A rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Research, 293, Article 113441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441

Paz, D. C., Bains, M. S., Zueger, M. L., Bandi, V. R., Kuo, V. Y., Cook, K., & Ryznar, R. (2022). COVID-19 and mental health: A systematic review of international medical student surveys. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 1028559. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1028559

Siegrist, M., & Zingg, A. (2014). The role of public trust during pandemics. European Psychologist, 19(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000169

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

Wilcha, R. (2020). Effectiveness of virtual medical teaching during the COVID-19 Crisis: Systematic review. JMIR Medical Education, 6(2), Article e20963. https://doi.org/10.2196/20963

Xiao, W. S. (2021). The role of Collectivism–Individualism in attitudes toward compliance and psychological responses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 600826. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.600826

Xiong, N., Fritzsche, K., Pan, Y., Löhlein, J., & Leonhart, R. (2022). The psychological impact of COVID-19 on Chinese healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(8), 1515–1529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02264-4

Yu, H., Li, M., Li, Z., Xiang, W., Yuan, Y., Liu, Y., Li, Z., & Xiong, Z. (2020). Coping style, social support and psychological distress in the general Chinese population in the early stages of the COVID-19 epidemic. BMC Psychiatry, 20, Article 426. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02826-3

Zhang, Q., Zhou, L., & Xia, J. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on emotional resilience and learning management of middle school students. Medical Science Monitor, 26, Article e924994. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.924994

*Lee Shuh Shing

Centre for Medical Education,

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine,

National University of Singapore, Singapore

10 Medical Dr, Singapore 117597

Email: medlss@nus.edu.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.