The state of Continuing Professional Development in East and Southeast Asia among the medical practitioners

Submitted: 5 July 2023

Accepted: 12 December 2023

Published online: 2 July, TAPS 2024, 9(3), 1-14

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-3/OA3045

Dujeepa D Samarasekera1, Shuh Shing Lee1, Su Ping Yeo1, Julie Chen2, Ardi Findyartini3,4, Nadia Greviana3,4, Budi Wiweko3,5, Vishna Devi Nadarajah6, Chandramani Thuraisingham7, Jen-Hung Yang8,9, Lawrence Sherman10

1Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care/ Bau Institute of Medical and Health Sciences Education, LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 3Medical Education Center, Indonesia Medical Education & Research Institute (IMERI), Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia; 4Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia; 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia/Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia; 6IMU Centre of Education and School of Medicine, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 7Department of Family Medicine, School of Medicine, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 8Medical Education and Humanities Research Center and Institute of Medicine, College of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan; 9Department of Dermatology, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan; 10Meducate Global, LLC, Florida, USA

Abstract

Introduction: Continuing medical education and continuing professional development activities (CME/CPD) improve the practice of medical practitioners and allowing them to deliver quality clinical care. However, the systems that oversee CME/CPD as well as the processes around design, delivery, and accreditation vary widely across countries. This study explores the state of CME/CPD in the East and South East Asian region from the perspective of medical practitioners, and makes recommendations for improvement.

Methods: A multi-centre study was conducted across five institutions in Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan. The study instrument was a 28-item (27 five-point Likert scale and 1 open-ended items) validated questionnaire that focused on perceptions of the current content, processes and gaps in CME/CPD and further contextualised by educational experts from each participating site. Descriptive analysis was undertaken for quantitative data while the data from open-ended item was categorised into similar categories.

Results: A total of 867 medical practitioners participated in the study. For perceptions on current CME/CPD programme, 75.34% to 88.00% of respondents agreed that CME/CPD increased their skills and competence in providing quality clinical care. For the domain on pharmaceutical industry-supported CME/CPD, the issue of commercial influence was apparent with only 30.24%-56.92% of respondents believing that the CME/CPD in their institution was free from commercial bias. Key areas for improvement for future CME/CPD included 1) content and mode of delivery, 2) independence and funding, 3) administration, 4) location and accessibility and 5) policy and collaboration.

Conclusion: Accessible, practice-relevant content using diverse learning modalities offered by unbiased content providers and subject to transparent and rigorous accreditation processes with minimal administrative hassle are the main considerations for CME/CPD participants.

Keywords: Medical Education, Health Profession Education, Continuing Professional Development, Continuing Medical Education, Accreditation

Practice Highlights

- Identifying professional practice gaps of clinicians should be the first step.

- The state of CME/CPD varies among countries and addressing relevant needs is crucial.

- Clinicians agreed that CME/CPD improves their skills and knowledge but lacked time to participate.

- Potential improvements include relevant content free from commercial bias and delivery mode.

- Systematic governance and aligned regulations by physician credentialing agencies is recommended.

I. INTRODUCTION

Lifelong learning is an essential skill for all healthcare professionals. This is particularly true when new models of healthcare delivery are being implemented and there is increased focus on outcomes and values such as shorter hospital stay, greater accountability and transparency and emphasis on patient engagement (Sachdeva, 2016; Vinas et al., 2020). Recent literature highlights that continuing medical education and continuing professional development programs (CME/CPD) are crucial in providing current contextually relevant educational and developmental activities in maintaining knowledge, skills, and performance for clinicians and have proven to be effective (Cervero & Gaines, 2015; Drude et al., 2019; Forsetlund et al., 2009). CME is defined as “educational activities which serve to maintain, develop, or increase the knowledge, skills, and professional performance and relationships that a physician uses to provide services for patients, the public, or the profession” (Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, n.d.), while CPD is usually a broader and more inclusive term referring to the combination of formal CME and other activities type that are designed to assist healthcare professionals to acquire skills and knowledge essential for their professional growth (Sherman & Chappell, 2018). Critical systematic reviews of the literature have shown that CME/CPD improves practice and support professional activities of medical practitioners to deliver best patient care (Cervero & Gaines, 2015; Sachdeva, 2016).

Although CME/CPD has undergone enormous changes and growth over the past 25 years, the advancement in CPD still considerably lag behind as compared to undergraduate and graduate medical education (Sachdeva et al., 2016). Goals and objectives in CME/CPD are often poorly defined and there is a paucity of the curricular structure for medical practitioners (Sachdeva, 2016). Despite consistent evidence sharing that formal CME/CPD activities, such as conferences and workshops, have little or no long-lasting effect on medical practitioners, many CME/CPD providers continue to include these approaches as their major educational offerings while clinicians continue to attend to improve their practice (Mann, 2002). Additionally, there are environments where CME/CPD is not mandatory, and in some instances, non-existent (Sherman & Nishigori, 2020).

Despite CME/CPD’s importance, the state of CME/CPD varies widely across regions and countries. Unlike Europe and the United States, there is no parallel accreditation system for CME/CPD in Asia. CME/CPD does not follow a standard process in all countries and the requirements are also different. A short summary of the CME/CPD system in the countries which are studied in this article is provided in Appendix 1. However, there is still a lack of empirical data in understanding the CME/CPD in Asia. Only one study was conducted in Japan to assess the state of CPD in the country and to identify the gaps in the understanding of the medical practitioners’ needs (Sherman & Nishigori, 2020). Hence, this study aims to explore the state of CME/CPD in the East and South East Asian region from the perspective of medical practitioners, and make recommendations for improvement.

A. Theoretical Framework

Researchers have been proposing few theoretical frameworks which are related to CME/CPD. For this study, we will be using the Process of Change and Learning framework by Fox et al. (1989) to provide an overarching view on the process of change and learning among medical practitioners. This will be further enhanced by using adult learning theory (Knowles, 1989).

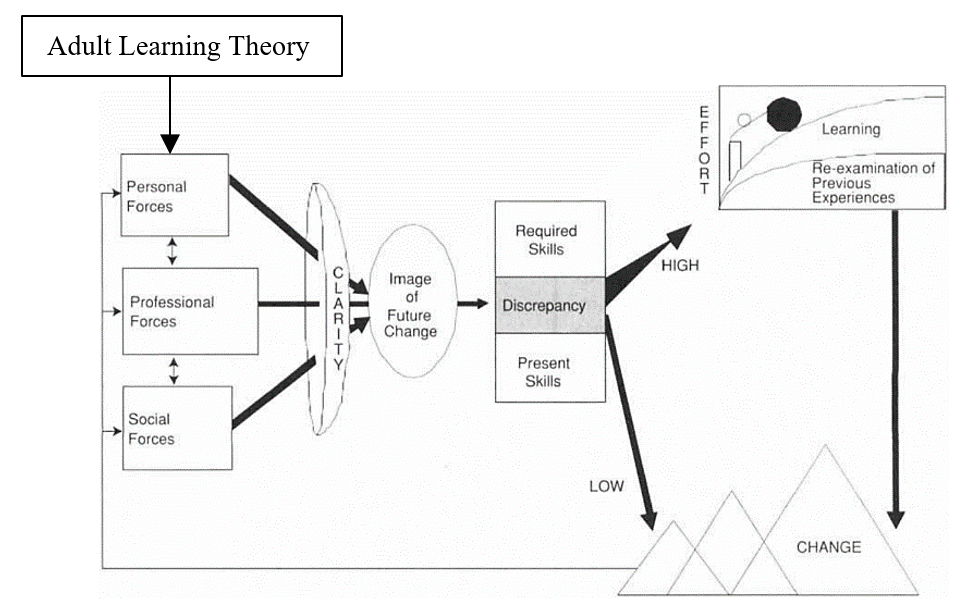

No discussion of practice informing theory in CME could exclude the work of Fox et al. (1989), who studied the process of change and learning in the lives of medical practitioners. They interviewed more than 350 medical practitioners to find out the types of learning activities that clinicians undertake and the important factors in the process of learning and change. The framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework related to CME/CPD using the process of change and learning (Fox et al., 1989) and adult learning theory (Knowles, 1989)

This framework clearly illustrated how change and learning occurs through several processes and how these changes were influenced by three forces. The actual process of change involves three iterative steps – preparing for the change, making the change, and sustaining or implementing the change in practice.

Through validated studies, we understand that there are three forces to prepare for the change, mainly personal, professional and social forces. Professional forces were found to be the most frequently motivated change. Personal forces, such as the desire for personal well-being, were infrequent and usually not the sole force for change. More often they were combined with professional forces, e.g. the desire to further one’s career. Social forces were also cited, usually combined with professional forces, e.g. relationships with colleagues.

Once the image of change has been developed, medical practitioners will evaluate the discrepancy between what new knowledge and skills are needed to achieve the change and estimate their current capacities. As shown in Figure 1, the perceived discrepancy is positively correlated with the effort that a medical practitioner will put in in learning. Therefore, the next step may involve attending a formal CME event if the discrepancy is high – to understand what is required and to assess or verify one’s own capabilities.

Although the Process of Change and Learning Framework provides us a big picture on how medical practitioners engaged in change and learning, it is insufficient to understand the humanist approach in understanding learning for human growth. It is widely recognised that autonomy and self-directed learning are the developmental nature for human desire to learn (Personal Forces). This behaviour is usually motivated by a mixture of external and internal motivation. This is important for the development of individuals toward autonomy, the self-directed learning, reflective practice and critical reflection, experiential learning, and transformative learning.

II. METHODS

This is a multi-centred study which employed a survey using a validated questionnaire and the section below will describe the data collection process, sampling of participants and data analysis coupled with a qualitative data gathering focus group with educational experts from each place participating. Five sites were involved in this study: Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan. Ethical approval was obtained from the respective Institutional Review Board [Reference Number: DSRB-2019-0449 (Singapore), UW 19-840 (HKU/HA HKW IRB) (Hong Kong), KET-1035/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPMetc.00.02/2019 (Indonesia), (CCH-IRB-200425) (Taiwan), IMU 467/2019 (Malaysia)].

The same questionnaire that was used and validated previously in Japan was modified for use in this region (Nishigori and Sherman, 2018). The questionnaire is a self-administered, 28-item test comprising 27 single or multiple-choice questions and an open-ended question for comments. Respondents were asked to rate on a 5-point Likert scale (Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree) for some of the questions. Demographic questions were included at the start of the survey (e.g. specialty, years of practice, prior participation in CME/CPD activities) followed by the following domains:

- Perceptions and satisfaction of clinicians with regard to current CME/CPD available for them

- Adequacy of the current CME/CPD available

- Impacts of CME/CPD in content coverage, evaluation, and development of learning

- Gaps in CME/CPD

- Future areas to focus on

The items were finalised following a group of experts’ meeting held in Singapore (March 2019) whereby the representatives (medical educationalists and medical practitioners) from participating sites discussed and went through the questions thoroughly. The meeting was moderated by an expert with over 28 years of experience in CME/CPD, and who designed the original study questionnaire. To add more local context and ensure that respondents were able to answer accurately, the questionnaire was translated into the native language and terms by the representatives in some locations.

Medical practitioners were invited to participate in the study. The study was conducted from July 2019 until May 2020. Voluntary, convenience, and snowball sampling was used and the representatives either disseminate the questionnaire link to their mailing list or through the various national organisation/institutions (Table 1) who then informed their members/faculty, in accordance with the ethics protocol guidelines. Reminders were sent until the response rate no longer increased. Implied consent was obtained from the participants when they proceeded to complete the survey after reading the information about the study on the first page.

|

Hong Kong |

Invitations sent by the local study investigators to members of the specialty colleges of the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, academic colleagues and doctors who teach medical students [Note: There was no institutional dissemination] |

|

Malaysia |

|

|

Indonesia |

|

|

Singapore |

|

|

Taiwan |

|

Table 1. Organisations/Institutions in each site which disseminated the questionnaire

A. Data Analysis

The investigators from Singapore collated the anonymised raw data file from the five locations and did the first round of analysis. For quantitative data, descriptive analysis was done using Microsoft Excel to compare the data across the 5 locations. For qualitative data (1 open-ended question related to future improvements), a content analysis was used to analyse the data by grouping comments with similar concepts and assigning an appropriate category. These processes were discussed and verified by 3 coders.

III. RESULTS

A. Demographics

The number of responses received is shown in Appendix 2, together with the data from key demographic questions. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Figshare repository – https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22345111 (Samarasekera et al., 2023).

In Malaysia and Singapore, Family Physicians made up the majority of their responses, with 43.86% and 44.29% respectively. Internal Medicine clinicians were the main participants in Hong Kong (60.00%) while 42.44% of the respondents in Indonesia were General Physicians.

As for primary practice setting, the majority of respondents from 4 of the sites were from university hospital/academic health centre – Singapore (34.29%), Hong Kong (40.0%), Indonesia (29.76%) and Taiwan (94.66%). For Malaysia, government/municipal hospital (26.96%) and government health clinic (based on the responses from “Others” field) were the most common work settings.

Moving to years in medical practice, many respondents from Indonesia and Malaysia (31.22% and 48.89% respectively) were relatively younger with only 6 – 10 years of practice. Conversely, Hong Kong had the most experienced pool of respondents with 44.00% having more than 25 years of practice.

The majority of the participants had prior medical education training – Singapore (75.71%), Indonesia (85.37%) and Malaysia (78.87%). However, the reverse was observed in Hong Kong (21.74%) and Taiwan (6.85%), which may be related to not catching meaning of the item.

B. Perceptions of the Current CME/CPD System

Regarding the CME/CPD status of the respondents and the system in their place, most were aware of the system, with over 90.00% for Singapore (95.38%), Hong Kong (92.00%) and Malaysia (99.52%). Indonesia (62.44%) and Taiwan (75.34%) had lower awareness.

Regarding the understanding the need for Inter-professional Continuing Education (IPCE) [involving more than one healthcare professions) CPD in their place, more than half of the respondents (Singapore – 75.38%, Hong Kong – 56.00%, Indonesia – 87.80%, Malaysia -72.01%, Taiwan- 69.86%) were aware.

Respondents from Singapore attended more CME/CPD events compared with the others in the year leading to the survey (35.38% attended 41-50 hours; 24.62% attended more than 50 hours). However, Indonesia had 24.10% of the clinicians who did not participate in any activity at all in the last 12 months while 54.97% participated between 11-30 hours. A similar pattern was noted in Taiwan with 13.70% of the participants having not attended and 52.06% participating between 11-30 hours.

Respondents strongly agreed and agreed that participating in some form of CME/CPD would increase their skills and competence (Singapore – 83.08%, Hong Kong – 88.00%, Indonesia -81.46%, Malaysia – 89.71%, Taiwan – 75.34%) and thereby ensuring that they have current knowledge that helps to provide the best care for their patients (Singapore – 84.62%, Hong Kong – 88.00%, Indonesia – 86.34%, Malaysia – 91.38%, Taiwan – 71.23%).

When considering whether participation in CME/CPD should be mandatory for all clinicians, there were 2 distinct groups– those whereby most respondents strongly agreed and agreed (Singapore – 80.00%, Hong Kong – 88.00%, Malaysia – 83.02%) compared to Indonesia (55.61%) and Taiwan (53.42%).

C. Perceptions of Industry-supported CME/CPD

Only 30.24% in Indonesia believed that the CME/CPD in their place is free from commercial bias. However, the number is slightly higher in Hong Kong (48.00%), Malaysia (42.11%) and Taiwan (45.21%) while those from Singapore (56.92%) were more confident that CME/CPD is free from bias.

The majority of the respondents knew that pharmaceutical companies commercially supported some of these programmes that were developed by an independent education provider (Singapore – 81.54%, Hong Kong – 80.00%, Indonesia – 82.44%, Malaysia – 79.67%, Taiwan – 72.60%). Despite these, a large number had participated in these programmes (Singapore – 87.69%, Hong Kong – 68.00%, Indonesia – 64.39%, Malaysia – 84.93%) except Taiwan (57.53%).

When asked about what they think about CME/CPD that is developed by an independent CME/CPD provider with financial support from the pharmaceutical industry, these were the top 3 responses, and the first two are actually misperceptions reported regarding independent CME/CPD:

- The pharmaceutical company can suggest speakers

- The pharmaceutical company works with the educational provider to develop content

- The content is developed independently by the education company to address the needs of the learners

The proportion of respondents who selected these 3 were quite comparable across all sites It is worth noting that none from Indonesia selected “the pharmaceutical company has no influence on the content and speaker selection”. Appendix 3 shows the full data for this question along with other key questions regarding perceptions of respondents to CME/CPD funded by industry.

While approximately 75% of the respondents in Singapore, Hong Kong, Indonesia and Malaysia strongly agreed and agreed that CME/CPD developed by independent CME/CPD providers and supported by the pharmaceutical industry would be beneficial to provide current and clinically important information, the number is smaller in Taiwan (61.64%). As to whether such programmes could be counted towards CME requirement, at least two-third of the respondents in Singapore (80.00%), Hong Kong (68.00%), Indonesia (75.61%), Malaysia (69.61%) agreed and strongly agreed, while only close to half from Taiwan (49.32%) felt that it should be counted. Taiwan’s practicing clinicians suggest CME/CPD is more appropriate to be developed by independent CME/CPD providers rather than supported by the pharmaceutical industry.

D. Future CME/CPD Programme

The survey also had a question comprising 7 options to find out more about clinicians’ preferences. In all 5 locations, the more common reason is that physician will choose an activity based on the relevance of the education to their practice (Singapore – 30.00%, Hong Kong – 26.44%, Indonesia – 31.16%, Malaysia – 31.22%, Taiwan – 23.76%) or their clinical specialty (Singapore – 23.50%, Hong Kong – 26.44%, Indonesia – 21.38%, Malaysia – 29.46%, Taiwan – 27.23%). The next common reason is curiosity for the topic (but not necessarily related to practice) – Singapore (18.50%), Hong Kong (17.24%), Indonesia (15.89%), Malaysia (16.59%), Taiwan (18.81%).

To have a better understanding on the needs of the clinicians regarding CME/CPD activities, respondents were asked on the items that is missing from the CME/CPD currently available to them. The lack of a variety of educational formats such as live, online/web-based, experiential program, preceptorships (Singapore – 17.58%, Hong Kong – 14.29%, Indonesia – 12.35%, Malaysia -13.33%, Taiwan – 20.37%) and shortage of innovative learning environments and new creative formats (Singapore – 18.18%, Hong Kong – 18.57%, Indonesia – 14.74%, Malaysia – 14.35%, Taiwan – 17.28%) were the top 2 choices selected by the respondents in each place. Appendix 4 shows the full data for this question. Among the comments given for “Others”, many respondents from Indonesia felt that current courses are pricy and free courses are scarce thus would like to see more of these. It should be noted that data collection was prior to COVID-19 and thus online learning was uncommon at that time.

Key barriers to participation included courses not offered at convenient times (Singapore – 36.00%, Hong Kong – 29.41%, Indonesia – 21.46%, Malaysia – 31.34%, Taiwan – 27.03%), followed by courses not covered in their budget and topics not relevant/clinically important. For those who selected “Others”, most of them re-emphasised one of the choices (not offered at convenient time) that they did not have time.

Finally, Singapore and Malaysia respondents preferred (1) authoring medical papers and books, (2) serving as a supervisory physician in undergraduate and post-graduate clinical training programs and (3) reading journal-based or other printed materials as their top 3 weighted average mode of CME/CPD. On the other hand, those from Indonesia, Malaysia and Taiwan preferred (1) hands-on learning, (2) live regional educational activities, including lectures, seminars, workshops, and conferences and (3) attending national and international conferences/symposia (in different order among the 3 locations).

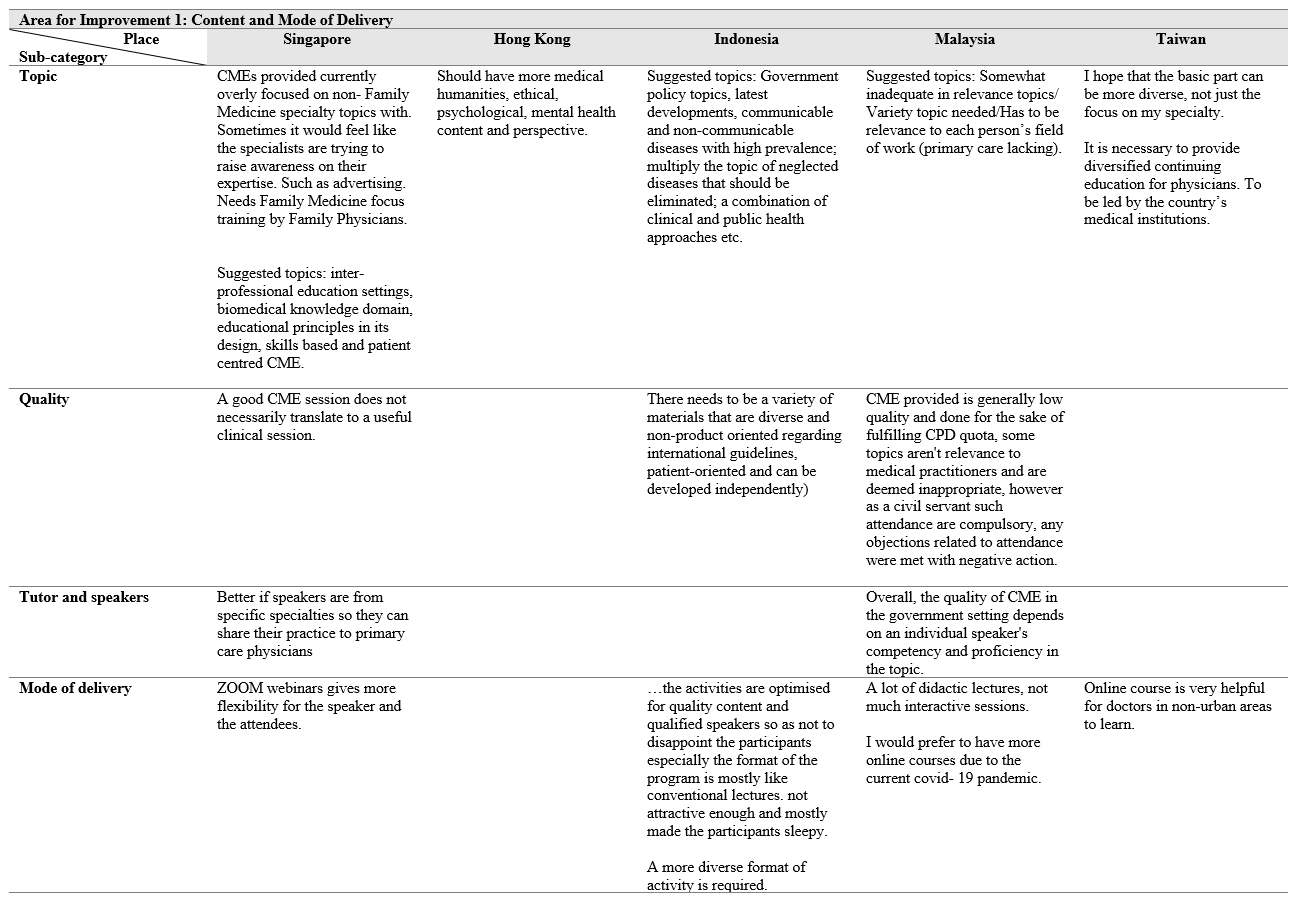

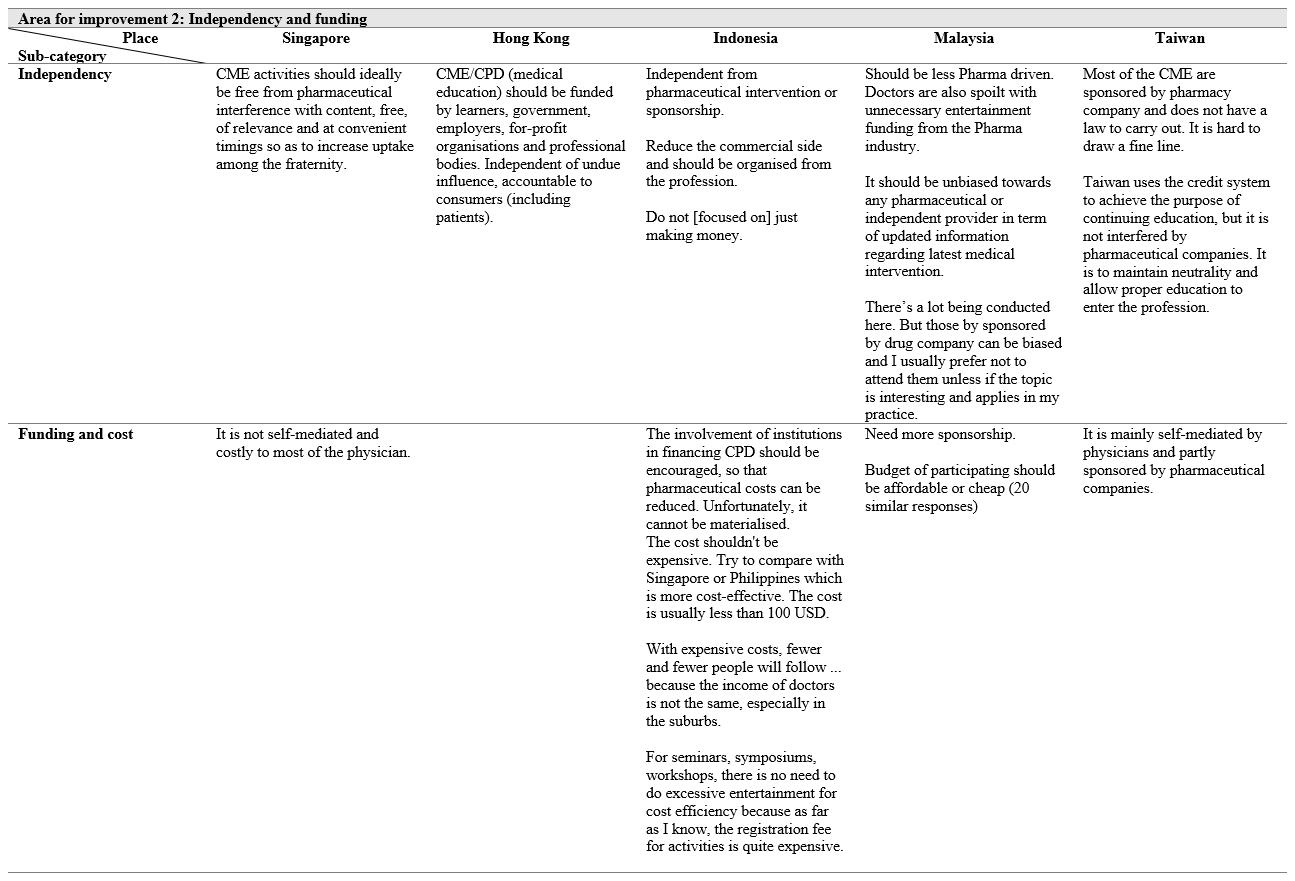

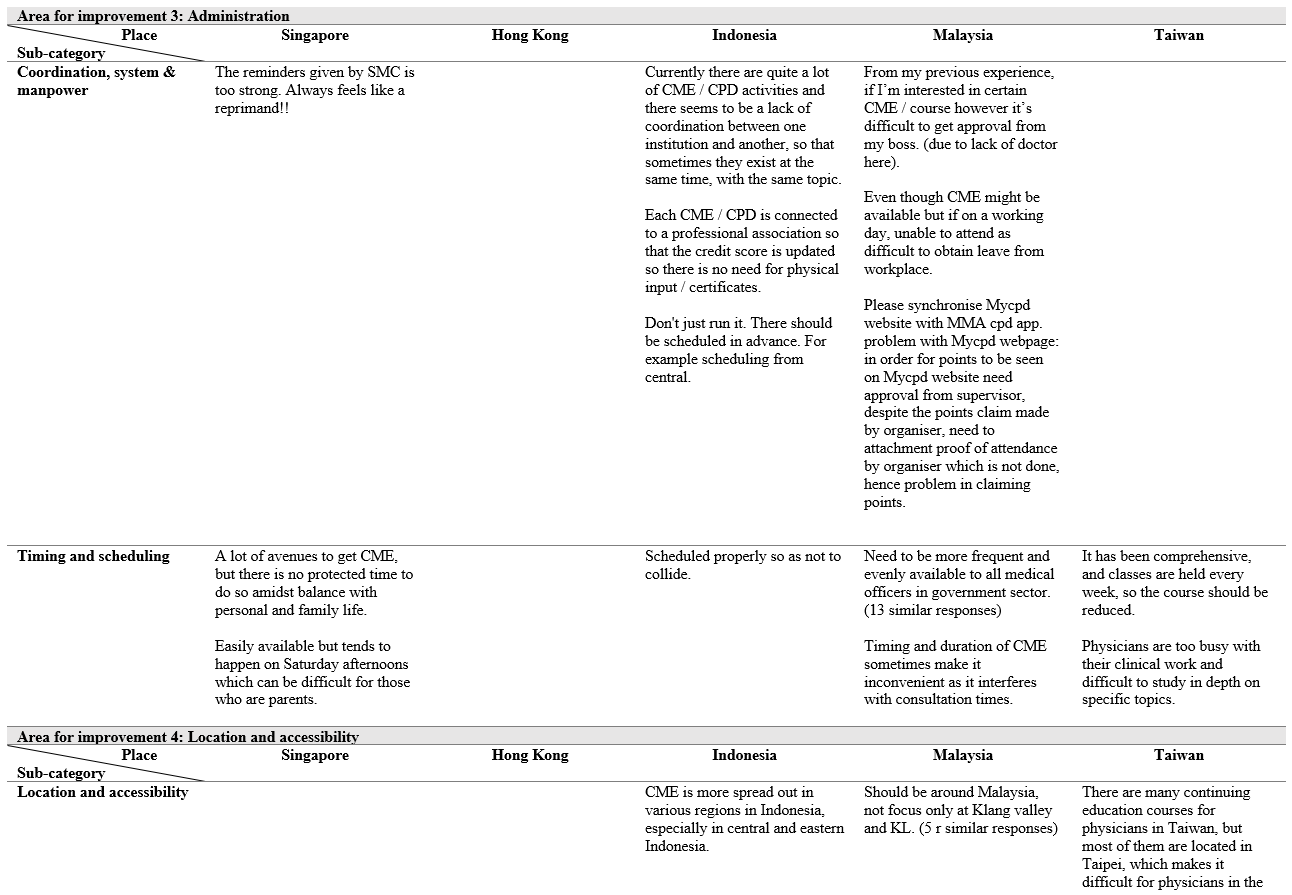

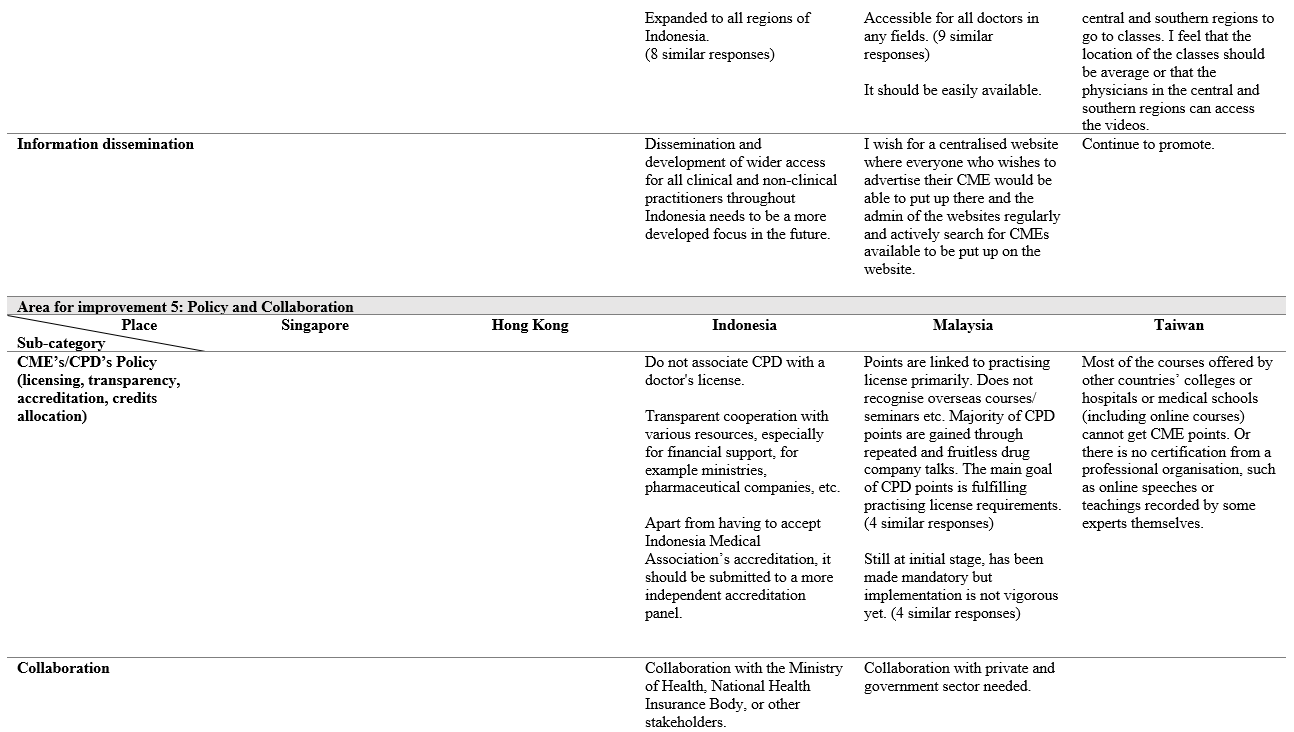

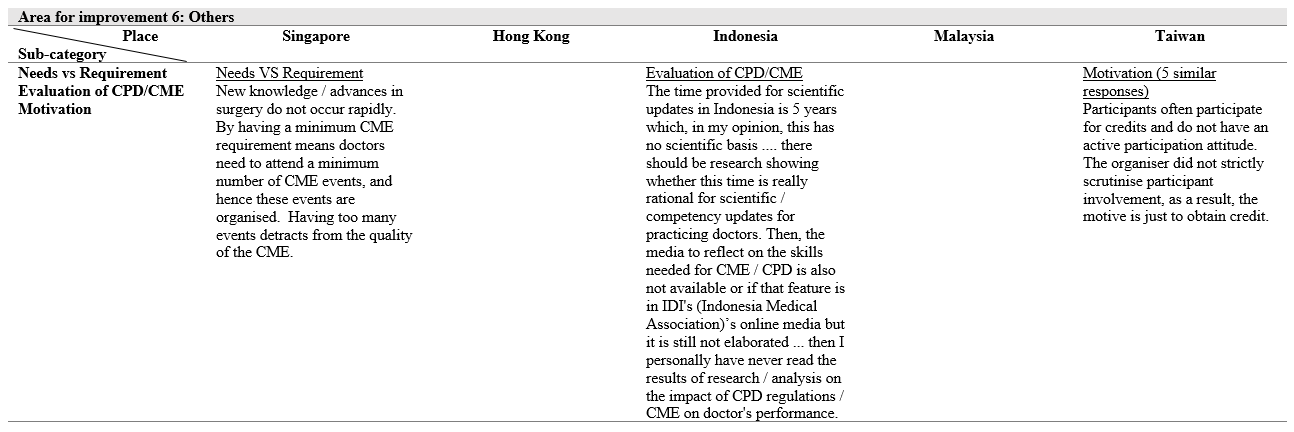

Although only one open-ended question was gathered from the participants, it had revealed rich data on the issues and challenges of CME/CPD in their own respective area. The positive comments received were quite generic. Mostly mentioned that the CME/CPD has been running well (Indonesia), acceptable and adequate, relevant and well-structured (Malaysia), still meeting the needs, adequate and organised (Taiwan) and comprehensive, structured CME for every month and good and adequate system in place with little bias in public institution (Singapore). The content analysis revealed 6 categories of areas of improvement as follows:

- Area for improvement 1: Content and mode of delivery

- Area for improvement 2: Independency and funding (includes cost)

- Area for improvement 3: Administration

- Area for improvement 4: Location and accessibility

- Area for improvement 5: Policy and collaboration

- Area for improvement 6: Others (motivation and evaluation)

IV. DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to survey the state of the CME/CPD systems in this region including clinicians’ perceptions on the involvement of the pharmaceutical industry and to see whether their perceptions are aligned with that of the accreditation organisations. These would allow the organisations to come up with relevant policies to improve the CME/CPD systems.

The survey seeks to explore several domains and first looked at their perceptions of the current CME/CPD programme. It is unsurprising that a large proportion of the respondents from all five areas were aware of the CME/CPD programme in their place and most strongly agreed and agreed that participating in some form of CME/CPD would increase their skills and competence (between 75.34% and 88.00%) and thereby ensuring that they have current knowledge that helps to provide the best care for their patients. This is higher than that of Japan whereby only 41% felt that their skills and competence has increased (Sherman and Nishigori, 2018).

However, while respondents from Singapore participated the most in these programmes, those from Indonesia and Taiwan did not participate as much and the two countries are also among the lowest when it comes to agreeing to make CME/CPD mandatory. This could be due to various reasons as highlighted by the question on barriers to the programmes, time constraint or accessibility (from qualitative question) or biasness against industry supported programme. Indeed, a study by Cook et al. on USA medical practitioners found that factors such as time and cost generally influence whether clinicians participate in CME/CPD activities, while topic was the key factor when choosing specific CME/CPD activities (reading an article, local activities, online courses, or attending a far-away course) (Cook et al., 2017).

Moving on to the perceptions of the industry supported CME/CPD programme, a low percentage of the respondents believed that the CME/CPD in their place is free from commercial bias. These observations are supported by qualitative comments such as “most of the CME are sponsored by pharmaceutical company and does not have a law to carry out. It is hard to draw a fine line.” (from Taiwan respondent) and “Do not [focused on] just making money (from new drug advertisement).” (from Indonesian respondent) which suggest that industry involvement is heavy in these locations. Miller and colleagues (2015) had previously looked at the credit systems in locations such as Indonesia. They found that the pharmaceutical industry provides substantial support through grants to the individual medical associations to cover the administrative and operational costs for conducting CME/CPD programmes, although membership fees also contributed to the funds (Miller et al., 2015). Good teaching requires sufficient financial resources. Internationally, most of the countries here have implemented ways to fund the training. In contrast, Indonesia is still facing funding issue and despite pharmaceutical support, medical practitioners still find that some courses are expensive. Therefore, transparency is required when working with pharmaceutical companies and there should be an independent accreditation panel for CME/CPD to ensure this transparency. Some European countries, such as Netherlands, Norway and France have even prohibited the sponsorship from pharmaceutical company for CME/CPD (Löffler et al., 2022).

Content and mode of delivery has been a common area for improvement which was raised by all 5 locations. They wanted to have more diversity and relevance to their fields for work. This is supported by the quantitative findings whereby the respondents in all five locations listed the top two factors they would use to decide whether to attend a programme – relevance of the education to their practice or their clinical specialty. Primary care/ family medicine related topic is lacking across the participating sites. Quality of the delivery is often dependent on the speakers and ZOOM is a more preferred method than didactic lectures. From the close-ended questions, respondents from all five locations would like to see a variety of educational formats (such as live, online/web-based, experiential program, preceptorships) and new creative formats. Online learning is also favourable to those who have limited access to CPD/CME. Comparing to other countries whereby peer exchange has been increasingly used as one of the teaching formats which will be awarded CME/CPD points, we are still lagging behind on how CME/CPD points should be awarded (Löffler et al., 2022). While it is required to register the CME/CPD activities before the event if medical practitioners of those events are to receive the points in countries such as Taiwan and Singapore via the CME Online Platform of Taiwan Medical Association (TMA) and Singapore Medical Council (SMC) respectively, the types of teaching formats which CME/CPD points can be awarded are restricted to activities which are conducted in the traditional formats. Due to the credit points system implemented, Taiwan’s participants expressed that motivation in attending CME/CPD has become chasing after the credit points rather than self-improvement. Malaysia, on the other hand, revealed that the CME/CPD system has just been made mandatory. The implementation of CME/CPD system in the countries examined still need to be more vigorous and flexible for the further development.

CME/CPD is also administratively challenging in Indonesia and Malaysia especially coordination in such huge countries. Hence, the CME/CPD often only takes place in the central part of the place which hinders some doctors from other regions from accessing the CME/CPD courses. Information dissemination is also affected as it is mostly populated in the central regions rather than the more rural regions. As a result, there is imbalanced training among the doctors in rural and urban regions. Having a system that automatically update the credit points instead of doing it manually and synchronisation of different systems to have an overview of the record are some challenges faced in Indonesia and Malaysia. This does not seem to be happening in other European countries as the organisation is carried out by numerous bodies or institutions in a structured manner and are accredited (Löffler et al., 2022). Therefore, operationalisation of CME/CPD will have to be streamlined so that more medical practitioners can benefit from it.

While personal forces and professional forces may motivate medical practitioners to improve their knowledge and skills by taking up courses in CME/CPD, a lack of support from the leaders and change in the system may deter the involvement. Participants have shared that difficulty in taking leave since it will interfere with consultation time, and a lack of doctors in the workplace have led to disapproval from the leader to join CME/CPD. Without proper protected time and resources, the lack of training for medical practitioners will continue to perpetuate.

A. Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, this study was conducted prior to the onset of COVID-19. Hence, some of the findings, especially those on the format of CME/CPD, may not be so relevant since most of these programmes are now online. Next, the response rate was not very high in some sites, and for some, many respondents were from the same work setting or speciality. Thus, the findings may not be fully generalisable in these aspects.

V. CONCLUSION

The medical associations in each place is tasked with coming up with educational programmes that meet the needs of a diverse physician workforce. A better understanding of the perspectives of its medical practitioners and implementation of relevant changes could improve clinical care. The recommendations shared in this paper may assist other medical associations with similar issues and for future development of CME/CPD for the countries.

Notes on Contributors

Dujeepa Samarasekera and Shuh Shing Lee designed and led the study in Singapore, contributed in the data collection and analysis, as well as in manuscript development.

Su Ping Yeo contributed to the data collection in Singapore, analysis and manuscript development.

Julie Chen designed and led the study in Hong Kong, contributed in the data collection and analysis, as well as in manuscript development.

Ardi Findyartini designed and led the study in Indonesia, contributed in the data collection and analysis, as well as in manuscript development.

Nadia Greviana led the data collection in Indonesia, contributed in the data analysis and manuscript development.

Budi Wiweko assisted in the study design in Indonesia, contributed in the data analysis and manuscript development.

Vishna Devi Nadarajah designed and lead the study in Malaysia, contributed to data collection, analysis and manuscript development.

Chandramani Thuraisingham contributed to data collection in Malaysia, analysis and manuscript development.

Jen-Hung Yang designed and lead the study in Taiwan, contributed to data collection, analysis and manuscript development.

Lawrence Sherman designed and led the study, contributed in the data collection and analysis, as well as in manuscript development.

Ethical Approval

This study was given an approval by the following:

Hong Kong: UW 19-840 (HKU/HA HKW IRB)

Indonesia: KET-1035/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPMetc.00.02/2019

Malaysia: IMU 467/2019

Singapore: NHG Domain Specific Review Board (2019/00449)

Taiwan: CCH-IRB-200425

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Figshare repository – https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22345111

Acknowledgement

The Hong Kong research team would like to thank Professor CS Lau (Dean) and Professor Gilberto Leung (Associate Dean (Teaching and Learning) of the LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong for their support and for facilitating survey administration and Ms Joyce Lai for research assistance.

The Indonesian research team would like to thank representatives from the Indonesian Medical Association, colleges and directors of specialty education programs who support this study by facilitating the survey administration.

The Malaysian research team would like to thank the Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia and the Academy of Medicine of Malaysia who supported this study by facilitating the survey administration.

Funding

This study was supported with funding from Pfizer.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding provided by Pfizer is purely to survey the state of CME/CPD in the region, with no commercial interest.

References

Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (n.d.). CME content: Definition and examples. ACCME. Retrieved June 23, 2021 from https://www.accme.org/accreditation-rules/policies/cme-content-definition-and-examples

Cervero, R. M., & Gaines, J. K. (2015). The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: An updated synthesis of systematic reviews. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 35(2), 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21290

Cook, D. A., Blachman, M. J., Price, D. W., West, C. P., Berger, R. A., & Wittich, C. M. (2017). Professional development perceptions and practices among U.S. physicians: A cross-specialty national survey. Academic Medicine, 92(9), 1335–1345. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001624

Drude, K. P., Maheu, M., & Hilty, D. M. (2019). Continuing professional development: Reflections on a lifelong learning process. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 42(3), 447–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2019.05.002

Forsetlund, L., Bjørndal, A., Rashidian, A., Jamtvedt, G., O’Brien, M. A., Wolf, F., Davis, D., Odgaard-Jensen, J., & Oxman, A. D. (2009). Continuing education meetings and workshops: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2009(2), Article CD003030. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2

Fox, R. D., Mazmanian, P., & Putnam, R. W. (1989). Changing and learning in the lives of physicians. Praeger.

Knowles, M. (1989). The making of an adult educator. Jossey-Bass.

Löffler, C., Altiner, A., Blumenthal, S., Bruno, P., De Sutter, A., De Vos, B. J., Dinant, G., Duerden, M., Dunais, B., Egidi, G., Gibis, B., Melbye, H., Rouquier, F., Rosemann, T., Touboul-Lundgren, P., & Feldmeier, G. (2022). Challenges and opportunities for general practice specific CME in Europe – A narrative review of seven countries. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), Article 761. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03832-7

Mann, K. V. (2002). Thinking about learning: Implications for principle-based professional education. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 22(2), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.1340220202

Miller, L. A., Chen, X., Srivastava, V., Sullivan, L., Yang, W., & Yii, C. (2015). CME credit systems in three developing countries: China, India and Indonesia. Journal of European CME, 4(1), Article 27411. https://doi.org/10.3402/jecme.v4.27411

Sachdeva, A. K. (2016). Continuing professional development in the twenty-first century. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 36(Suppl 1), S8–S13. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000107

Sachdeva, A. K., Blair, P. G., & Lupi, L. K. (2016). Education and training to address specific needs during the career progression of surgeons. The Surgical clinics of North America, 96(1), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2015.09.008

Samarasekera, D. D., Lee, S. S., Yeo, S. P., Chen, J., Findyartini, A., Greviana, N., Wiweko, B., Nadarajah, V. D., Thuraisingham, C., Yang, J. H., & Sherman, L. (2023). Data from Each Participating Country [Dataset]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22345111

Sherman, L. T., & Chappell, K. B. (2018). Global perspective on continuing professional development. TheAsia Pacific Scholar, 3(2), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-2/GP1074

Sherman, L., & Nishigori, H. (2020). Current state and future opportunities for continuing medical education in Japan. Journal of European CME, 9(1), Article 1729304. https://doi.org/10.1080/21614083.2020.1729304

Vinas, E. K., Schroedl, C. J., & Rayburn, W. F. (2020). Advancing academic continuing medical education/Continuing professional development: Adapting a classical framework to address contemporary challenges. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 40(2), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000286

*Dujeepa D. Samarasekera

10 Medical Drive,

Singapore 117597

Email address: dujeepa@nus.edu.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.