Exploring ethical challenges in Singapore physiotherapy practice: Implications for ethics education

Submitted: 12 May 2022

Accepted: 3 August 2022

Published online: 3 January, TAPS 2023, 8(1), 13-24

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-1/OA2810

Audrey Lim1, Vicki Xafis2 & Clare Delany3

1Health and Social Sciences Cluster, Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT), Singapore; 2Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia; 3Department of Medical Education, School of Medicine, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

Abstract

Introduction: Workplace contexts, including political and sociocultural systems influence health professions’ perception and experience of ethical issues. Although established health ethics principles are relevant guiding values, they may be experienced and interpreted differently within different health contexts. How should ethics education account for this? This paper presents ethical dilemmas and concerns encountered by physiotherapists practicing in Singapore and discusses the implications for ethics education.

Methods: Qualitative methods informed by interpretivism and phenomenology were employed. In-depth interviews with 42 physiotherapists from different workplace settings in Singapore were conducted. Participants described everyday ethical challenges they encountered. Inductive content analysis was used to analyse the interview transcript data.

Results: Ethical issues occurred within and across three spheres of ethics: micro, meso and macro. Ethical issues at the micro sphere centered around physiotherapist-patient relationships, interactions with colleagues, and therapists’ feelings of moral distress. In the meso sphere, ethical challenges related to influences arising from the organizational resources or systems. In the macro sphere, ethical challenges developed or were influenced by sociocultural, religious, economic, and political factors.

Conclusion: The findings reflect current literature indicating that context can influence ethical situations, as experienced and perceived by physiotherapists in their unique settings. Such empirical data might inform the development of ethics curricula to ensure that universal ethical principles are situated within the realities of clinical practice. Locally relevant and realistic ethical case studies will better enable students to recognise and address these situations.

Keywords: Ethics, Physiotherapy, Health Professions Education, Ethics Education, Asian Context, Singapore, Healthcare Principles, Health Ethics Principles

Practice Highlights

- Context can influence the ethical situations experienced and interpreted by healthcare professionals.

- Contextualised cases studies need to be developed to make ethics real and relevant to students.

- Ethics education should incorporate local context and not focus only on ethics epistemic knowledge.

- Ethics education should incorporate the dynamic influence of macro, meso and micro factors.

I. INTRODUCTION

The established health ethics principles articulated by Beauchamp and Childress (2001): autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice guide healthcare practice, including physiotherapy (Carpenter & Richardson, 2008; Edwards, Delany, et al., 2011). Although these principles were originally proposed as universally relevant and foundational to health ethics, health professionals interpret them differently, depending on their professional and personal background, their values, and the culture of the community and settings in which they work (Fuscaldo et al., 2013). In physiotherapy ethics scholarship, there is growing recognition that the universal nature of principlism as a supporting ethical decision-making framework, may not be a sufficient guide for physiotherapists in their ethical decision-making, because of the plurality of values and diverse contexts of healthcare practice (Carpenter, 2010; Carpenter & Richardson, 2008; Edwards, Wickford, et al., 2011; Fryer et al., 2021; Greenfield, 2006; Hudon et al., 2019; Oyeyemi, 2011; Souri et al., 2020; Sturm et al., 2022). Consequently, there is increasing pedagogical interest in using case studies drawn from everyday practice to bring authenticity and contextual relevance to ethics education (Aguilar-Rodríguez et al., 2019; Fuscaldo et al., 2013).

In physiotherapy, empirical studies have shown that different work contexts, political and sociocultural systems have a direct influence on physiotherapists’ perception and experience of ethical issues (Delany et al., 2018; Fryer et al., 2021; Sturm et al., 2022). A recent example is the study of ethical issues physiotherapists experienced by Sturm et al. (2022). The authors reported physiotherapists working in specific countries described having to compromise their professional integrity due to overt threats and intimidation by suppressive professional organisations or leaders. They were directed to follow the societal or organisational hierarchies or risk jeopardizing their careers. Studies of ethical experiences of physiotherapists practicing in the African nations (Aderibigbe & Chima, 2019; Chigbo et al., 2015; Nyante et al., 2020; Oppong, 2019; Oyeyemi, 2011) and the Greater Middle East region (Edwards, Wickford, et al., 2011; Qamar et al., 2014; Souri et al., 2020) similarly discussed how cultural influences, such as religion or spirituality can directly affect ethical practice and decision-making. Despite increasing empirical evidence globally, the influence of cultural and societal contexts on ethical decision-making and therapists’ interpretation of health values has not been examined in the East and Southeast Asian regions. There has also been little exploration of how societal and cultural context in which physiotherapy is practiced might be used to inform and shape curricula for ethics education.

In this paper, we present data about the ethical situations physiotherapists in Singapore encounter in their everyday clinical practice. Singapore is multi-racial, multi-religious and multi-cultural. The values of Singaporean people are very much rooted in their Asian heritage, with Confucianism as the prevailing social model (Ong, 2020; Tan, 1989; Yang et al., 2006). This research aims to contribute to knowledge about the influence of context on clinical ethical issues and decision-making, as interpreted by physiotherapists in Singapore. The empirical data will then be used to inform subsequent ethics curricula. Identifying and analysing the factors influencing ethical issues, as they are experienced and interpreted by physiotherapists in the Singaporean context, is an important pedagogical strategy to inform the development of health ethics curricula.

II. METHODS

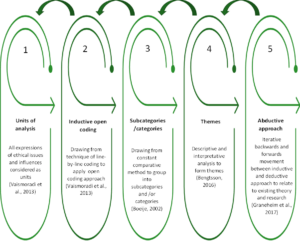

We used a qualitative methodology drawing on the research paradigm of phenomenology and conducted in-depth interviews. We recruited physiotherapy clinicians using purposive (Palys, 2008) and snowball sampling (Holloway & Galvin, 2016). Written and verbal consent was obtained. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by AL and ranged from 44 to 123 minutes. Audio recordings were professionally transcribed verbatim and were reviewed by AL. Content analysis was used to analyse the transcribed data, with interviewer’s written field notes as supporting reference. Data was systematically coded and categorised with the aim of identifying themes, their frequency, and relationships, through both description and interpretation (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Lindgren et al., 2020; Vaismoradi et al., 2013). Assisted by QSR NVivo 12 Software, the data analysis was organised into five steps (Figure 1). Although illustrated as a linear, chronological sequence, analysis occurred in a non-linear, iterative manner till there was clarity and meaning in the themes that were identified.

Figure 1. Sequence of data analysis

III. RESULTS

A total of 42 physiotherapists from four settings: acute, community, specialised institutions, and private practice participated (Table 1). All participants have been practicing physiotherapists in Singapore for the past three years, with 33.3 % in geriatrics and neuro rehabilitation, 45.3% in musculoskeletal and sports, and 21.4% in cardiopulmonary and other niche specialties. Thirty-six participants are Singaporeans and six are from Malaysia, Philippines, Hong Kong, New Zealand, and the UK. Ages ranged from 27 to 54 years old.

|

WORK SETTINGS |

ACUTE

Restructured public hospitals & subsidiaries |

COMMUNITY

Government supported intermediate & long- term care facilities |

SPECIALISED INSTITUTIONS

Government supported facilities for medical specialties/ niche populations

|

PRIVATE

Independent private physio clinics |

TOTAL (n) |

|

Number of Participants (n) |

16 |

13 |

6 |

7 |

42 |

|

Percentage (%) |

38.1 |

31.0 |

14.3 |

16.6 |

100 |

|

Gender (n) |

|

||||

|

Female |

9 |

12 |

5 |

2 |

28 |

|

Male |

7 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

14 |

|

Age Group in Years (n) |

|

||||

|

26-35 |

10 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

19 |

|

36-45 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

15 |

|

46-55 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

8 |

|

Professional Qualifications (n) |

|

||||

|

Diploma/Degree |

7 |

9 |

2 |

1 |

19 |

|

Postgraduate |

9 |

4 |

4 |

6 |

23 |

|

Number of Years in Healthcare (n) |

|

||||

|

< 10 |

9 |

6 |

1 |

2 |

18 |

|

10-20 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

17 |

|

> 20 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

n = number of participants

Table 1. Participants demographics

Six key themes were identified from the ethical situations described by the participants in their everyday physiotherapy practice: 1) managing healthcare resource constraints – encompassing ethical situations regarding the financial cost of healthcare, resource limitations and healthcare system inadequacies, 2) conforming to healthcare norms in Singapore – covering particular ethical challenges related to Singapore’s sociocultural context, including healthcare norms, 3) negotiating the complexity of the work environment – comprising challenges participants encountered in fulfilling their multiple obligations, especially in a negative work environment, 4) adapting to the intricacies of different healthcare settings – representing the unique ethical issues specific to the four different settings in Singapore, 5) balancing professional obligations and personal wellbeing – emerging from the participants’ struggle with their duty as moral agents, entrusted with the care of their patients while safeguarding their personal wellbeing and 6) advocating for patients: the predicament of relationships – exploring the relational aspects of a physiotherapist’s role, including defining professional boundaries, advocating for patients while managing their responsibilities to patients’ family and their colleagues. Complete quotes (QN1- QN18) illustrating the six themes are presented in Table 2.

|

Themes |

Quotations (QN) |

|

Managing healthcare resource constraints |

QN1: “I feel that these boundaries are set…because… at the end of the day it’s [healthcare] a business … we have to meet our finances. We have to balance our cheque books”. (P25) QN2: “If it’s something beyond our control, like the health system in Singapore itself, it can also be a potential barrier to our ethical practice. Because it’s not that we don’t want to do it. But … our hands are tied and it’s because of all these external factors that is affecting us.” (P38) |

|

Conforming to healthcare norms in Singapore |

QN3: “The subsidized cases actually are more complex than the private patients because private patients once they have a problem, they will get medical attention immediately… Whereas the subsidized patients…they usually drag…if they are being managed by a fresh grad that has no idea what is going on, then I think is unfair for them. And so, the cases that they [juniors] see, a lot of time is much more complex than the cases that the seniors see.” (P15) QN4: “I think insisting on certain types of equipment that we don’t feel or don’t agree with, that the patient really needs, but we do have to give because the doctor will keep on insisting on it, no matter how much we tell them that it may not be beneficial to the patient and all that. I think that’s one of the ethical things that I feel that I encounter.” (P33) QN5: “Breaking bad news seems to be also a bit of a two-way thing, where you have to go around to the family member first, before telling the patient even now. I mean, 20 years ago when I first started work it was like that, and I thought it would have moved on right? No. So I think is the education and is the perception of our Asian values, of the very paternalistic values that I think our families, or our patient’s families have.” (P09) |

|

Negotiating the complexity of the work environment |

QN6: “Because all you [i.e. the organisation] care about is earning money, all you [i.e. the organisation] care about is how many patients I can see a day and not caring whether I see it well, I’m seeing it correctly, whether I have provided value to the client.” (P13) QN7: “I see a patient, I read the history and I do the minimum, I do no harm. Patient may not get very well or recover as fast as they should…In terms of assessment, we need to be a bit more holistic, we need to assess thoroughly, but we don’t have the time…to me is clinically not ethical, but that’s how we’ve been working in a clinical setting because of time constraint, resources constraint.” (P22) QN8: “When I see something, I will just say it out to my superior, hoping that something can be done. And I can say it a few times, but once I see this is not going to work, because simply nobody responds to you, then just have to let it be, or if you really cannot take it, then you leave the organization.” (P15) |

|

Adapting to the intricacies of different healthcare settings |

QN9: “So, the proper procedure is that we refer them back to the doctor and get a new referral for the new problem. I find it quite silly to do that, the patient is right in front of me, and I know what’s the problem. I can instantly give a solution to the problem, why do I need to go and get a referral, and then delay for another three months before the patient can come back and see me for another problem?” (P26 – in acute setting) QN10: “If I make this person too mobile, family member cannot cope, he’s falling down, so this is my moral dilemma. I want him to be better, physically better. But he’s moving all over the place and he’s prone to fall and he’s much bigger size than the carer, (who) is only 40kg. I’m in a moral dilemma, how much should I give? How much should I train, or should I just give a little bit more just to maintain him? Must see from carer’s perspective. I don’t live with the person. I can come in once in a while, that one hour or just 45 minutes. But this person stays 24 hours, that’s where I’m stuck.” (P02 – in community setting) QN11: “However, then comes to work organisation that you need to understand the needs of the organisation and even the greater picture, therefore, you may not give the patient the best anymore.” (P03 – in specialised institution setting) QN12: “It’s very correlation or causation, or whatever. Often the treatment plan will miraculously be the same length as the [number] of sessions given by insurance, which you know is coincidence right? That it always happens to be the same length. You’ve got 10 sessions via insurance. That’s how long it’s going to take you to get better.” (P29 explained in a satirical manner – in private practice clinic) |

|

Balancing professional obligations and personal wellbeing

|

QN13: “Yes, so every day, we’ll carry him out on a chair for two hours… we’ll carry him back to bed and it’s two to three times max assist…this actually gave my senior some backache…because every day, is every day…because for such heavy patient, there’s no real technique already… So, this is a dilemma.” (P36) QN14: “Because I thought it was like part of my job. Probably he accidentally touched…when we do transfer, it tends to like, hands go flare anywhere. So, I thought never mind because I need to do my job. I need to transfer him. Of course, I don’t want him to fall down. So, I have to do all this contact.” (P34) QN15: “If it is a young female patient, then you try to have the female TA (therapy assistant) to be in as your chaperon. If it’s Ah Ma (older lady), then just keep the door open. It’s okay. I don’t know how is that right or wrong. But so far, it doesn’t give me any problem with that kind of practice. Usually, the Ah Ma doesn’t complain.” (P11) |

|

Advocating for patients: the predicament of relationships |

QN16: “Of course, the patient did give verbal consent. So, by right, by legal standpoint, it means that it’s fine. Then you start thinking a little bit deeper, sometimes when you’re in a clinic, patient will actually feel that they have to do that. If they don’t agree to your examination, then they are here for no purpose…Does it make the patient feel that we are coercing them? And they don’t really have a choice to really say, I don’t want it in that sense.” (P41) QN17: “I’m trying to fight for my client’s welfare. But a lot of times, if the family do not seek that welfare for the client, there is nothing I can do…. Do I train the caregiver who’s not willing to learn? Do I charge this family when the family has already expressed interest in no longer paying for equipment, or even therapy? Do I force it down their throat?” (P04)

QN18: “I guess maybe to me it really depends on the extent of that incident, how bad of that it is to the profession as a whole. If it is something that is minor and understandable, then probably I will not. But if it is something that is…pretty bad, maybe I would. I don’t know, it’s still a struggle, I can’t because it’s my fellow friends and colleagues. So, it’s a bit tough to be honest.” (P27) |

Table 2. Quotes to illustrate the six themes

A. Managing Healthcare Resource Constraints

Participants were aware of their ethical responsibility to act in the patient’s best interest in the provision of care but felt the pressure of finite resources and financial constraints (QN1). They described how they struggled to fulfill their professional obligations whilst at the same time managing patients’ expectations about availability of resources. Some therapists found loopholes to bypass government funding requirements. One participant (P26) summarised it as being a “discrepancy between the ideal care for the nation as a whole versus what is ideal for the patient’s health right before my eyes”. Some participants spoke about how key performance indicators (KPIs) intended to manage healthcare costs can drive change in organisational and clinician behaviour to practice defensively rather than using evidence-based practice to meet patients’ needs. Participant 09 described it as “funding drives behaviour” and gave the example of how a KPI that tracks fall rates may sway clinicians to be overly conservative to prevent falls, rather than challenging patients’ balance to maximise recovery. A lack of clear workflows and integration between different clinical settings was another ethical challenge preventing best available care for patient. Community and private practice physiotherapists indicated that they lack access to medical records and diagnostic results to seek clarity on a patient’s condition. This resulted in therapists feeling frustrated, as they had to delay treatment or proceed without a clear understanding of the patient’s medical status (QN2).

B. Conforming to Healthcare Norms in Singapore

For some participants, the allocation of only senior clinicians to private patients and junior clinicians to subsidised patients was viewed as unjust practice, where allocation of clinicians’ expertise is not based on the needs of patients. Participant 15 shared that the subsidised patients tended to be more complex cases as they may not have the resources to seek medical attention early (QN3). Most participants acknowledged this as an accepted practice in Singapore’s healthcare system and not just specific to physiotherapy, with participant 39 highlighting that “no one addresses it”. Adding to the social class differentiation, nearly all participants commented on the acceptance of hierarchical differentiation in healthcare with doctors at the top. Many participants spoke about paternalism being widely practiced and accepted by patients, and shared incidents where doctors dictated treatment plans, and even overrode patients’ wishes. Participants felt obliged to comply regardless of their own professional judgement (QN4).

Familialism may also compromise patients’ autonomy. Participants shared stories where family members dominated decision-making or demanded withholding information from patients. There were also geriatric patients who chose to relinquish their autonomy to their children. Many participants viewed this as an accepted part of Asian norms (QN5). A few participants stressed that many Singaporeans still hold conservative views and highlighted the importance of remaining sensitive to racial, religious, and cultural differences. For example, participant 22 disclosed that it is not accepted practice for male physiotherapists to place electrocardiogram (ECG) leads on a female patient even with the patient’s consent and a chaperon present.

C. Negotiating the Complexity of the Work Environment

Organisations have to manage the financial cost of patient care and ensure business sustainability. With resource limitations, clinicians face the challenge of conflicting obligations to their organisation and their patients. Participant 13 expressed her frustration and resentment that physiotherapy outcomes are determined by organisational financial values (QN6). Another participant (P31) shared how she had to discharge patients “prematurely” to meet organisational expectations. Other participants coped by settling for minimum treatment and doing no harm to patients (QN7).

Adding to this complexity was a negative work culture, expressed by participants as the pressure to conform to the organisation’s expectations, norms, and practices. Examples given included unreasonable workloads, biasness towards preferred staff, belittling remarks, fault-finding, and masked threats of poor appraisals. Staff were expected to conform and follow the rules, leading to a culture of fear, where safety incidents went unreported for fear of repercussions. This was further perpetuated by the lack of supervisors’ moral courage, who ignored such ethical infringements, thus normalizing ethical silence as accepted behaviour. Participant 13 disclosed her moral distress when her concerns regarding fraudulent behaviour by a colleague who falsely documented and charged for services, were disregarded by her seniors. Some participants dispiritedly added that often no action was taken and they either learnt to accept the status quo and found their own solutions or left the organisation (QN8).

D. Adapting to the Intricacies of Different Healthcare Settings

1) Acute settings: The different organisational structure and systems in each setting gave rise to specific ethical concerns. Many ethical issues in the acute settings related to the structured systems, established practices and workflows. One such practice was physiotherapists not being allowed as first contact practitioners in public institutions. Patients can only be seen with a referral from doctors and only be treated for the problem for which they were referred. This was ethically challenging for physiotherapists wanting to manage patients holistically (QN9). Several participants also raised concerns regarding minimal charging per session. In some acute settings, the on-call duty was rostered for all physiotherapists, regardless of their inpatient competency or speciality. Concerns were raised about whether this was ethically good clinical practice and in patients’ best interests.

2) Community settings: Some participants commented that community settings have varied and diverse services, making it difficult to implement guidelines that are applicable and fair to all services. This can encourage clinicians to circumvent the rules to benefit their patients. In integrating a patient back to their community, the patient’s psychological, social, and family issues can become the major consideration. Participant 02 shared her dilemma in having to factor in the caregiver’s coping ability when progressing a patient with mental health issues, who had little comprehension of fall risks, to independent mobility (QN10). A few participants commented that community physiotherapists generally have greater independence and flexibility in their work schedule, but this can engender accountability issues in terms of documentation and the standard of services provided. Some participants felt that the lack of awareness of community services available and an unsubstantiated perception that community physiotherapists are not as skilled, may deter some patients from continuing their care in the community and could have contributed to a shortage of community allied health professionals.

3) Specialised institutions: For some specialised institutions where healthcare is not the core business, physiotherapists reported being constrained by the organisational goals when caring for their patients. The needs of the organisation and the deliverables expected factored greatly in both the patient’s and clinician’s decision-making. Consequently, the best interest of the patient may not take precedence (QN11). Participants commented that the hierarchical order in such institutions tended to be more overt, with instructions directed by leaders in charge rather than team discussions.

4) Private practice clinics: Participant 27 described the business aspect of private practice as having to wear two hats: one as a clinician and one as a businessman. This can lead to maximising profits through overcharging, overservicing and maximising insurance claims. Participant 27 further disclosed that most people kept it hushed, “it’s one of those things that everyone knows is happening, but no one wants to rock the boat”. Participant 29 shared how he had to see post-op cases twice weekly, regardless of whether it was necessary, “because that’s just the way things are done” and how the cost of treatment or number of sessions needed for recovery consistently matched the insurance claim limits (QN12). Other participants raised issues which bordered on being illegal. One common example shared was fee-splitting, whereby commission was given for the referral of patients. Private clinicians commented that private practice is loosely regulated, with no standardisation or best practice guidelines and that there is little collaboration or accountability to the profession. They further elaborated that private practice is very competitive, with some clinicians making exaggerated claims about their skills or effectiveness of their treatment.

E. Balancing Professional Obligations and Personal Wellbeing

Participants described conflicts between their work responsibilities and their personal wellbeing. They shared their insecurities about whether they had positively fulfilled their professional obligations. Demanding expectations or long working hours imposed by organisations forced some participants to sacrifice their personal life, compromise their mental health and even sustain work-related injuries. Participants detailed episodes of transferring or ambulating patients without equipment or sufficient manpower (QN13). The nature of physiotherapy often requires close physical contact with patients. Participant 34 disclosed her distressing encounter with a patient with mental health issues, who repeatedly touched her inappropriately but denied it. On why she continued treatment, she replied that she needed to do her job and convinced herself that it was probably accidental (QN14). Participant 11 shared his dilemma with regard to treating female patients when there was a lack of chaperones. To protect staff from allegations of misconduct, it is accepted practice to leave the consultation room door open, leading to a possible violation of patients’ privacy (QN15). Participants also disclosed unethical and even illegal incidents which reflected the therapists’ conflict between protecting themselves and their professional responsibilities. These included false documentation of clinical notes, dishonesty about treatment errors, or not reporting safety violations.

Having self-doubt about one’s competency, whether it is due to inexperience, being out of practice or due to a lack of access to resources led some participants to question whether they had done patients a disservice or whether they were practicing beyond their capability. At times, clinicians also found it challenging to bill patients for physiotherapy services, especially if patients had financial difficulties.

F. Advocating for Patients: The Predicament of Relationships

Several participants highlighted the crossing of professional boundaries as an ethical concern. This included patients constantly calling or messaging, asking for free advice or personal favours. The nebulous zone where a professional relationship crossed over into friendship or even a dependency worried many participants. Numerous participants shared their turmoil when dealing with special populations such as patients with mental health conditions. The dilemma of overriding a patient’s autonomy became harder to resolve when the patient’s safety was at risk or where there was a possibility of detrimental consequences. Participant 41 pondered about the unspoken power differential between the patient and the healthcare professional, which can lead to patients feeling pressured to consent to treatment (QN16).

Another common dilemma expressed by participants was gaining caregivers’ and families’ support. Family members felt justified in their demands as the payer and viewed themselves as the spokesperson. Some participants expressed their helplessness with family members unwilling to pay for needed services or equipment (QN17).

Participants shared views about maintaining collegiality and not disrespecting colleagues’ viewpoints, specifically when there were conflicting patient management strategies. Some participants resented the loss of their professional autonomy but yielded to maintain harmony, and to avoid confusion for the patient. A number of participants reinforced this strong sense of fraternity, including unwillingness to expose wrongdoing even if colleagues had crossed ethical and legal boundaries (QN18). Some participants spoke about the move towards transdisciplinary practice in Singapore and the blurring of professional boundaries. One participant (P04) elaborated on resource limitations in home-based therapy, prompting her to take on other healthcare roles to prescribe home equipment and even change patients’ wound dressings. She expressed her dilemma in having to consider the patient’s perspective, her organisation’s views, and her own competency as well as the professional and legal implications of providing the wrong advice.

Further analysis revealed that the ethical challenges encountered mapped to the three overall spheres of ethics previously identified by Glaser (2005) and Sippel et al. (2015), namely the micro, meso and macro spheres. Ethical issues at the micro sphere centered around physiotherapist-patient relationships, physiotherapist’s interactions with colleagues and their own needs. The meso sphere consists of four quarters that represented the four settings, and issues included structural problems and challenges related to organizational resources or systems. The macro sphere comprises ethical issues rooted in the influence of cultural, sociological, religious, economic, and political contexts (Sippel et al., 2015). The modified illustration of spheres of ethics with the meso sphere encircling the micro sphere and the macro sphere encircling the meso sphere, show the connection and interdependence of all three spheres (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Spheres of ethics (six themes)

IV. DISCUSSION

This study is the first to report on the clinical ethics issues faced by physiotherapists practicing in Singapore. It also provides some insights into the influence of context in ethical decision-making. The six themes identified were further organised into micro, meso and macro spheres or contexts of ethics. The micro sphere themes included ethical issues that have previously been identified in other physiotherapy study findings (Delany et al., 2018; Fryer et al., 2021; Praestegaard & Gard, 2013; Sturm et al., 2022). The notable points of difference specific to Singapore were themes residing in the meso and macro spheres. These themes offered potential insights into the particular context of physiotherapy practice in Singapore. One example in the meso sphere is the influence of different healthcare settings (acute, community, specialised institutions, and private practice) on ethical dimensions of physiotherapy practice within Singapore’s healthcare system. There were differences in the predominance or perceived importance of certain ethical issues due to each setting’s unique organisational structure and systems. These findings appear to reflect current literature which reported on differences in physiotherapists’ ethical experiences due to the influence of healthcare settings (Cantu, 2018, 2019; Hudon et al., 2015).

At the macro sphere, participants reported that fulfilling government set KPIs or outcome measures which determined healthcare funding exerted indirect pressure on them. They grappled with patients’ expectations of advocacy on their behalf and societal expectations of cost containment (Dronberger, 2003). In meeting the requirements, participants had to balance their view about what was a good enough treatment constrained by the system, versus the best treatment available. The findings suggest that having to meet quantitative statistical numbers such as discharge rates was interpreted by some therapists as neglecting the quality of care and negatively affecting the therapist-patient relationship. This finding is consistent with that of Hudon et al. (2015), who highlighted institutional and economic influence on the quality of physiotherapy service and public trust. Another theme in the macro sphere concerned the negative effects of hierarchies and power differentials, which therapists believed led to paternalistic practice. Factors contributing to paternalism can include time limitations on treatment, patient’s literacy levels, societal values of respecting seniority and the accepted practice of patients handing over decision-making to authority or their family. Familialism is prevalent in Singaporean culture, where a family centric approach or interest will outweigh individual’s autonomy (Krishna, 2012). It is viewed as an accepted part of Asian values and needs to be acknowledged in order to provide the best possible care for the patient. Ethical issues related to familialism have also been reported by studies in the African context (Chigbo et al., 2015; Nyante et al., 2020; Sippel et al., 2015).

A. Relevance to Ethics Education

There is agreement that ethics cannot be taught independent of context, with a focus only on the epistemic knowledge, but that it needs to incorporate the dynamic influence of macro, meso and micro factors (Barradell, 2017; Cantu, 2018; Greenfield et al., 2015; Ladeira & Koifman, 2017). The themes in this study can directly inform the ethics curriculum, highlighting to students the influence of resource constraints, local healthcare norms, organisational culture, challenges of different settings, as well as balancing multiple obligations. Beyond awareness, students must be equipped with the abilities and skillsets to address and navigate these ethical situations. Elaboration on each theme’s implications for the local ethics curriculum is outlined in Table 3.

|

Spheres of ethics |

Themes |

How understanding of spheres of ethics can inform physiotherapy ethics curricula |

|

MACRO: Conflict of ethical principles versus societal expectations, culture, and practices |

Managing healthcare resource constraints |

· Incorporate understanding of financial aspects of healthcare and its influence on physiotherapy practice (Finch et al., 2005). · Learn to anticipate and navigate the potential conflicts between equitable use of resources (justice) and best care for each patient (beneficence). |

|

Conforming to healthcare norms in Singapore |

· Be consciously aware of local cultural and practices. Acknowledging and respecting both universal health ethics principles and culturally based differences in values by taking into account relevant contextual considerations in application of ethical principles (Fuscaldo et al., 2013). · Learn to reason and negotiate for common moral ground without compromising one’s moral integrity (Fuscaldo et al., 2013). |

|

|

MESO: Contention between ethical principles and organisational values and norms |

Negotiating the complexity of the work environment |

· Recognise the complexities of the work environment, including managing obligations to employers versus professional duty to their patients. · Develop strategies and skillsets to overcome negative work culture (e.g. by building an advisory support system and network within the organisation or the national professional body). |

|

Adapting to the intricacies of different healthcare settings |

· Understand the strengths and limitations of different workplace settings in Singapore and potential ethical challenges. |

|

|

MICRO: Conflict of ethical principles or the struggle between self-interest versus altruism |

Balancing professional obligations & personal wellbeing |

· Reinforce importance of personal integrity and learn coping strategies for self -care to prevent professional burn out or moral distress. |

|

Advocating for patients: the predicament of relationships |

· Appreciate that relational aspects of physiotherapy practice go beyond patient-therapist interactions to include colleagues and caregivers. · Emphasise physiotherapists’ role as a moral agent and advocate for patients. |

Table 3. Implications for ethics curricula

The study findings can be used to inform the development of realistic and contextualised case studies that have the potential to resonate with students’ clinical experience and improve the relevance of ethics education (Barnitt & Roberts, 2000; Fuscaldo et al., 2013; Triezenberg & Davis, 2000). The data in this study highlighted therapists’ emotions of frustration, anger, and concern. Disregarding contextual differences may create indifference, cynicism, or even moral distress when students begin practice and experience the realities of clinical practice (Greenfield & Jensen, 2010; Mohr & Mahon, 1996; Nalette, 2010). Students may dismiss ethics as irrelevant or feel disrespected that their culture and practices have not been considered in the materials taught (Fuscaldo et al., 2013).

Developing realistic case studies for ethics curricula has four possible effects: 1) it assists in dispelling the notion that ethics is based on abstract and idealist considerations (Seedhouse, 1995), 2) it can stimulate practical reflection and be action guiding to help students reason and navigate ethical challenges (Geddes et al., 2009; Swisher et al., 2012), 3) it can address the dissonance between what they learn in the classroom and what they experience in clinical practice (Dutton & Sellheim, 2017), 4) it can assist to increase ethics literacy and ethical courage. Case studies based on local experiences can provide the physiotherapy community with the ethical language to express their thoughts (Barnitt & Partridge, 1997). This shared language may enable students and clinicians to share experiences and learn how to speak up or seek help. Only when ethical issues that are pertinent to the local physiotherapy community are voiced, articulated, and discussed, can there be engagement of the community to confront identified ethical concerns, commit to creating change, and to strive towards ethical clinical practice.

B. Limitations

Participant recruitment and interviews were completed under the permeating influence of the global COVID crisis amidst shortage of healthcare staff. Due to the sensitivity of the topic, participants may have been guarded and not freely shared their views.

V. CONCLUSION

This study explored the ethical issues experienced and interpreted by physiotherapists across a range of practice settings in Singapore and examined how these experiences could inform ethics education. Our results have further substantiated current literature that context plays a critical influencing role on ethical situations, as they are experienced and perceived by physiotherapists in their unique geographical and clinical settings. The ability to act ethically has to be understood within the context and complexity of the sociocultural and political framework, along with the explicit and implicit influences, obligations, and commitments as part of a community, in order to directly address the everyday frustrations and concerns that clinicians face in trying to provide the best care for patients. With this knowledge, ethics educators and clinical supervisors will be better equipped to prepare students for clinical practice in Singapore.

Notes on Contributors

AL reviewed the literature, conceptualised and designed the study, conducted the interviews, analysed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript and wrote the final version submitted. This study is part of her PhD thesis.

CD is the first author’s primary PhD supervisor, who is involved in finalising the study and manuscript conceptualisation, and supervised the study from the beginning to the final version of the manuscript.

VX is the first author’s local PhD supervisor for data collection and supervised the study from the beginning to the final version of the manuscript.

Both CD and VX gave critical feedback on the direction and writing of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of Melbourne, Medicine and Dentistry Human Sub-Committee on 25 October 2019 (ID 1955123), and from the Singapore Institute of Technology, Institutional Review Board on 25 November 2019 (Project 2019146).

Data Availability

As the topic is of a sensitive nature and part of a larger PhD study, transcripts from the interviews are confidential and the authors do not have consent to upload onto a repository.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the 42 participants who have consented and graciously gave their time to participate in this study.

Funding

This study was completed with support from Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT) SEED grant (R-MOE-E103-C019).

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Aderibigbe, K. S., & Chima, S. C. (2019). Knowledge and practice of informed consent by physiotherapists and therapy assistants in Kwazulu-Natal Province, South Africa. South African Journal of Physiotherapy, 75(1), a1330. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajp.v75i1.1330

Aguilar-Rodríguez, M., Marques-Sule, E., Serra-Añó, P., Espí-López, G. V., Dueñas-Moscardó, L., & Pérez-Alenda, S. (2019). A blended-learning programme regarding professional ethics in physiotherapy students. Nursing Ethics, 26(5), 1410–1423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017748479

Barnitt, R., & Partridge, C. (1997). Ethical reasoning in physical therapy and occupational therapy. Physiotherapy Research International, 2(3), 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.v2:3

Barnitt, R. E., & Roberts, L. C. (2000). Facilitating ethical reasoning in student physical therapists. Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 14(3), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001416-200010000-00007

Barradell, S. (2017). Moving forth: Imagining physiotherapy education differently. Physiotherapy Theory & Practice, 33(6), 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2017.1323361

Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2001). Principles of biomedical ethics. Oxford University Press.

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

Boeije, H. (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity, 36, 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1020909529486

Cantu, R. (2018). Physical therapists’ perception of workplace ethics in an evolving health-care delivery environment: A cross-sectional survey. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 35(8), 724–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2018.1457744

Cantu, R. (2019). Physical therapists’ ethical dilemmas in treatment, coding, and billing for rehabilitation services in skilled nursing facilities: A mixed-method pilot study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(11), 1458–1461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.06.013

Carpenter, C. (2010). Moral distress in physical therapy practice. Physiotherapy Theory & Practice, 26(2), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.3109/09593980903387878

Carpenter, C., & Richardson, B. (2008). Ethics knowledge in physical therapy: A narrative review of the literature since 2000. Physical Therapy Reviews, 13(5), 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1179/174328808×356393

Chigbo, N. N., Ezeome, E. R., Onyeka, T. C., & Amah, C. C. (2015). Ethics of physiotherapy practice in terminally ill patients in a developing country, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 18(7), S40–S45. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.170826

Delany, C., Edwards, I., & Fryer, C. (2018). How physiotherapists perceive, interpret, and respond to the ethical dimensions of practice: A qualitative study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 35(7), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2018.1456583

Dronberger, J. (2003). Fraud and negligence in physical therapy practice: A case example. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 19(3), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593980307961

Dutton, L. L., & Sellheim, D. O. (2017). Academic and clinical dissonance in physical therapist education: How do students cope? Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 31(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001416-201731010-00009

Edwards, I., Delany, C. M., Townsend, A. F., & Swisher, L. L. (2011). New perspectives on the theory of justice: Implications for physical therapy ethics and clinical practice. Physical Therapy, 91(11), 1642–1652. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20100351.10

Edwards, I., Wickford, J., Adel, A. A., & Thoren, J. (2011). Living a moral professional life amidst uncertainty: Ethics for an Afghan physical therapy curriculum. Advances in Physiotherapy, 13(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.3109/14038196.2010.483015

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Finch, E., Geddes, E. L., & Larin, H. (2005). Ethically-based clinical decision-making in physical therapy: Process and issues. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 21(3), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593980590922271

Fryer, C., Sturm, A., Roth, R., & Edwards, I. (2021). Scarcity of resources and inequity in access are frequently reported ethical issues for physiotherapists internationally: An observational study. BMC Medical Ethics, 22, Article 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00663-x

Fuscaldo, G., Russell, S., Gillam, L., Delany, C., & Parker, M. (2013). Addressing cultural diversity in health ethics education: Final Report 2013. http://www.research-matters.com.au/publications/FinalReport.pdf

Geddes, E. L., Salvatori, P., & Eva, K. W. (2009). Does moral judgement improve in occupational therapy and physiotherapy students over the course of their pre-licensure training? Learning in Health and Social Care, 8(2), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-6861.2008.00205.x

Glaser, J. W. (2005). Three realms of ethics:An integrating map of ethics for the future. In R. B. Purtilo, G. M. Jensen, & C. B. Royeen (Eds.), Educating for moral action: A sourcebook in health and rehabilitation ethics (pp. 169-184). F.A. Davies.

Graneheim, U. H., Lindgren, B. M., & Lundman, B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today, 56, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

Greenfield, B., & Jensen, G. M. (2010). Beyond a code of ethics: Phenomenological ethics for everyday practice. Physiotherapy Research International, 15(2), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.481

Greenfield, B. H. (2006). The meaning of caring in five experienced physical therapists. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 22(4), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593980600822859

Greenfield, B. H., Jensen, G. M., Delany, C. M., Mostrom, E., Knab, M., & Jampel, A. (2015). Power and promise of narrative for advancing physical therapist education and practice. Physical Therapy, 95(6), 924-933. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140085

Holloway, I., & Galvin, K. (2016). Data analysis: Procedures, practices and use of computers. In Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare(4th ed., 287–302).Wiley-Blackwell.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Hudon, A., Drolet, M. J., & Jones, B. W. (2015). Ethical issues raised by private practice physiotherapy are more diverse than first meets the eye: Recommendations from a literature review. Physiotherapy Canada, 67(2), 124–132. https://doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2014-10

Hudon, A., Ehrmann Feldman, D., & Hunt, M. (2019). Tensions living out professional values for physical therapists treating injured workers. Qualitative Health Research, 29(6), 876–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318803589

Krishna, L. R. (2012). Best interests determination within the Singapore context. Nursing Ethics, 19(6), 787–799. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733011433316

Ladeira, T. L., & Koifman, L. (2017). Interface entre fisioterapia, bioética e educação: revisão integrativa [Interface between physical therapy, bioethics and education: Integrative review]. Revista Bioética, 25(3), 618–629. https:/doi.org/10.1590/1983-80422017253219

Lindgren, B. M., Lundman, B., & Graneheim, U. H. (2020). Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103632

Mohr, W. K., & Mahon, M. M. (1996). Dirty hands: The underside of marketplace health care. Advances in Nursing Science, 19(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-199609000-00005

Nalette, E. (2010). Constrained physical therapist practice: An ethical case analysis of recommending discharge placement from the acute care setting. Physical Therapy, 90(6), 939–952. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20050399

Nyante, G. G., Andoh, C. K., & Bello, A. I. (2020). Patterns of ethical issues and decision-making challenges in clinical practice among Ghanaian physiotherapists. Ghana Medical Journal, 54(3), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.4314/gmj.v54i3.9

Ong, E. K. (2020). The impact of sociocultural influences on the COVID-19 measures—reflections from Singapore. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(2), e90–e92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.022

Oppong, S. (2019). When the ethical is unethical and the unethical is ethical: Cultural relativism in ethical decision-making. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 50(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.24425/ppb.2019.126014

Oyeyemi, A. (2011). Ethics and contextual framework for professional behaviour and code of practice for physiotherapists in Nigeria. Journal of the Nigeria Society of Physiotherapy, 19(1–2), 49–53. https://academicjournals.org/journal/JNSP/article-full-text -pdf/0AA592B65221

Palys, T. (2008). Purposive sampling. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The sage encyclopedia of qualittaive research methods (Vol. 2, pp. 697–698). Los Angeles: Sage.

Praestegaard, J., & Gard, G. (2013). Ethical issues in physiotherapy – Reflected from the perspective of physiotherapists in private practice. Physiotherapy Theory & Practice, 29(2), 96–112. https://doi.org/10.3109/09593985.2012.700388

Qamar, M. M., Basharat, A., Rasul, A., Basharat, S., & Ijaz, M. J. (2014). Perception of physical therapy students and professionals about the importance of professional ethics. International Journal of Medicine and Applied Health., 2(2), 57–61. https://www.academia.edu/11604067/perception_of_physical_therapy_students_and_professionals_about_the_importance_of_professional_ethics

Seedhouse, D. (1995). There’s Logic, and then there’s what we do around here. Health Care Analysis, 3(2), 87–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02198208

Sippel, D., Marckmann, G., Atangana, E. N., & Strech, D. (2015). Clinical ethics in Gabon: The spectrum of clinical ethical issues based on findings from in-depth interviews at three public hospitals. PLoS ONE, 10(7), e0132374. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132374

Souri, N., Moghadam, A. N., & Shahbolaghi, M. (2020). Iranian physiotherapists’ perceptions of the ethical issues in everyday practice. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal, 18(2), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.32598/irj.18.2.221.5

Sturm, A., Edwards, I., Elizabeth Fryer, C., & Roth, R. (2022). (Almost) 50 shades of an ethical situation-international physiotherapists’ experiences of everyday ethics: A qualitative analysis. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2021.2015812

Swisher, L. L., Kessel, G. V., Jones, M., Beckstead, J., & Edwards, I. (2012). Evaluating moral reasoning outcomes in physical therapy ethics education: stage, schema, phase, and type. Physical Therapy Reviews, 17(3), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743288X12Y.0000000011

Tan, C. H. (1989). Confucianism and nation building in Singapore. International Journal of Social Economics, 16(8), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068298910133106

Triezenberg, H. L., & Davis, C. M. (2000). Beyond the code of ethics: Educating physical therapists for their role as moral agents. Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 14(3), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001416-200010000-00009

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

Yang, S., Shek, M. P., Tsunaka, M., & Lim, H. B. (2006). Cultural influences on occupational therapy practice in Singapore: a pilot study. Occupational Therapy International, 13(3), 176–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.217

*Audrey Lim

Health and Social Sciences Cluster

Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT)

10 Dover Road

Singapore 138683

+65 6592 3390

Email: Audrey.Lim@SingaporeTech.edu.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.