The conceptualisation of educational supervision in a National Psychiatry Residency Training Program

Submitted: 19 May 2021

Accepted: 26 August 2021

Published online: 4 January, TAPS 2022, 7(1), 66-75

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-1/OA2521

Lay Ling Tan1, Pim W. Teunissen2, Wee Shiong Lim3, Vanessa Wai Ling Mok1 & Hwa Ling Yap1

1Department of Psychological Medicine, Changi General Hospital, Singapore; 2School of Health Professions Education (SHE), Maastricht University, Netherlands; 3Cognition and Memory Disorders Service, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Development of expertise and counselling skills in psychiatry can be mastered only with effective supervision and mentoring. The conceptualisations of educational supervision amongst supervisors and residents were explored in this study to understand how supervisory roles may have been affected by the adoption of competency-based psychiatry residency training.

Methods: A qualitative research approach with thematic analysis was adopted. Individual in-depth interviews using a semi-structured interview guide with a purposive sample of six supervisors and six newly graduated residents were conducted. Transcripts of the interview were analysed and coded using the Atlas Ti software.

Results: Four major themes emerged from analysis of the transcripts: (1) Meaning and definition of supervision; (2) Expectations and responsibilities of the educational supervisor; (3) Elusiveness of mentoring elements in educational supervision and (4) Personal and professional development of residents in supervision. Supervisors and residents perceived educational supervision narrowly to be transactional with acquisition of knowledge and skills, but residents yearned for more relational interactions.

Conclusion: This study showed that the roles and functions of supervisors in educational supervision were unclear. It also highlighted the lack of a mentoring orientation in supervision in the psychiatry residency training program. An emphasis on assessment of competencies might have contributed to tension in the supervisory relationship and lack of a mentoring role, with concerns on residents’ personal and professional identity development in their psychiatry training.

Keywords: Psychiatry, Mentoring, Educational Supervision, Competency-Based Medical Education, Professional Identity Development

Practice Highlights

- Supervision in psychiatry has been described to encompass more than just a teaching and learning relationship but also a supportive and mentoring one.

- Educational supervision has been purported to offer the unique opportunity for effective mentoring within supervision.

- This qualitative study highlighted significant differences in definitions, roles and expectations of educational supervision.

- The conflict between mentoring and appraisal of competency needs to be addressed.

- Roles and expectations of the educational supervisor must be articulated clearly to both supervisors and residents.

I. INTRODUCTION

Postgraduate medical education (PGME) in Singapore underwent tremendous changes in the last decade. Before 2009, Singapore’s PGME was structured around time frames and curricular processes, in contrast to competency-based medical education (CBME) (Frank et al., 2017). In 2008, Singapore’s Ministry of Health (MOH) raised concerns of the lack of clear learning objectives and absence of measurable standards of training and outcomes with the medical schools and teaching hospitals. MOH recognised a need to ensure that every PGME graduate is prepared for clinical practice with the necessary competencies. With that vision in mind, MOH collaborated with the United States (US) Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) to revamp the PGME structure and accreditation system in 2009 (Chay, 2019). This move has resulted in major changes in the psychiatry postgraduate program. The 5-year National Psychiatry Residency Training Program was launched with a main teaching site and six sponsoring institutions. It also instituted the educational supervision framework where an assigned educational supervisor meets the supervisee regularly during the whole duration of training.

A. Concepts of Supervision

Supervision originated in professions outside of medicine (Launer, 2013) and is a distinct professional practice with specific articulated competence and training (Falender & Shafranske, 2007). It has been considered as a combination of various elements and is not a uniform concept (Carroll, 2006). Supervision is critical for ensuring effective professional practice of the healthcare sector (Tebes et al., 2011), particularly in psychiatry, where counselling skills can be developed only with effective supervision and mentoring.

1) Clinical supervision: Clinical supervision is subcategory to the wider concept of supervision. One definition is “provision of guidance and feedback on matters of personal, professional and educational development in the context of a trainee’s experience of providing safe and appropriate care” (Kilminster et al., 2007). There is consensual acceptance of the basic functions of clinical supervision: formative, supportive and managerial (Kilminster et al., 2007). These functions overlap depending on the context, problems emphasised and supervision goals (Kadushin, 1985).

2) Educational supervision: Educational supervision, on the other hand, has been described as regular supervision occurring in the context of a training program to determine learning needs and review progress of the supervisee (Passi, 2016). There has been extensive research done in clinical supervision (Kilminster et al., 2007; Patel, 2016) but educational supervision is under-researched with very few such studies conducted in psychiatry. It can be considered to be the most complex and challenging form of supervision as there are a number of overlapping and at times conflicting roles which need to be fulfilled (Launer, 2013). Aside from having to facilitate learning, there is also the need to evaluate the supervisee’s performance, which may result in confusion in the supervisory roles. Educational supervision has been purported to offer the unique opportunity for effective mentoring within supervision (Passi, 2016), which ideally should be recognised as an important component of the whole supervisory framework (Driessen et al., 2011).

B. Conceptual Framework for Educational Supervision in Postgraduate Psychiatry Training

Clinical and educational supervision are essential for development of health professionals and widely recognised as crucial for effective learning (Pront et al., 2016) and reflective practice (Schon, 1987). Learning in educational supervision can be conceptualised from experiential and social learning theory. Experiential learning is a key concept of the developmental-educational model of educational supervision (Kolb, 1984/2014). Learning is also a social process, where the supervisee is influenced by the cultural system of social knowledge and learns the trade with the guide of a more experienced colleague (Vec et al., 2014), a particularly important component in the field of psychiatry, a discipline closely related to the social sciences. Thus, there has been frequent reference to this apprenticeship model in supervision, although there is no clear definition of the term in the context of psychiatry training (MacDonald, 2002).

Supervision in psychiatry has its roots in psychoanalysis (Torby et al., 2015). Supervision in the context of general psychiatry training was mentioned infrequently and the concepts of supervision of the psychotherapeutic work of trainees were often transferred directly into the setting of general clinical supervision as if the two situations were identical (MacDonald, 2002). The supervisor can be seen as fulfilling the role of the analyst of the supervisee’s analytic ego (Akhtar, 2009). This necessitates a trusting relationship between the supervisor and supervisee, very much akin to that of informal mentoring, which has been described as psychosocial in nature and serves to enhance the supervisee’s self-esteem through interpersonal dynamics of the relationships, the emotional bonds they form and the work they accomplish together (Hansman, 2001). Supervision has also been frequently conceptualised as a development process or a process of identification (MacDonald, 2002). This is the transformation of a trainee through the acquisition of requisite knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, and attributes; from doing the work of a psychiatrist to being a psychiatrist (Wald, 2015). This active, constructive and transformative process has been referred to as professional identity formation (Wald, 2015). This continuous process requires the fostering of personal and professional growth through mentorship and self-reflection (Holden et al., 2015). The provision of guidance and mentoring with respect to personal and professional identity development would arguably be more critical in supervision in psychiatry. The personal aspects and the development of better self-awareness in the supervisee and the ‘internalised supervisor’ has been considered by some to be the fundamental goal of supervision (Kadushin, 1985). However, this will require the training program to allow sufficient time and opportunity to build and develop the supervisor-supervisee relationship.

With ACGME setting up collaborative initiatives with other countries and a trend towards a competency-based training approach, a better understanding of the impact of CBME on the supervision process and structure will be relevant to our international educators. The mentoring element in educational supervision has the potential to ensure that learning is not guided entirely by assessment and evaluation but is supplemented by the periodic guidance of a trusted mentor and addressing the personal and professional components in clinical supervision (Kilminster et al., 2007). With the implementation of the ACGME training framework, understanding the complexity and barriers of developing a mentoring relationship in educational supervision will be crucial. The research questions which this study aimed to answer were:

1. What are supervisors’ and residents’ perceptions on the educational supervisory role in the psychiatry residency program?

2. How do supervisors and residents perceive the supervisor’s mentoring roles in their educational supervision experience?

II. METHODS

A. Design

This was a qualitative research strategy where individual in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of six supervisors and six residents were conducted, the intent of which was to understand the participants’ meanings of the phenomenon of educational supervision (Creswell, 2014). Ethics approval was sought from the Institutional Review Board (CIRB Ref: 2017/2319) and informed consent was received from all participants.

B. Setting

The residency training program instituted the educational supervision framework by ACGME where an assigned educational supervisor meets the supervisee weekly of at least an hour duration. The educational supervisor is responsible for completion of the resident’s evaluation reports based on feedback gathered from the resident’s clinical supervisors and offer recommendations for the supervisee’s training progress. Clinical supervisors in the residency program are consultants managing patients together with the residents in the ward and clinic settings. Work-placed based assessments in the form of mini-clinical evaluations (mini-cex) and 360-degree feedback evaluations are done by both the educational and clinical supervisors.

There are six teaching sites in the psychiatry residency program and the researcher’s teaching site is one of the largest, with 18 supervisors overseeing nine to 12 residents posted in their various years of training. The setting of the research was the teaching site where the PI (Principal Investigator) served as Associate Program Director (APD).

C. Subjects

Six supervisors with two each from the Associate Consultant, Consultant and Senior Consultant group, and one male and one female from each group were invited to participate. For the residents, those who had just graduated from the residency program were invited. A total of six recently graduated residents (three males and three females) were sampled. This was to minimise biases related to fear of negative evaluation or power differentials while still undergoing residency training. It was hoped that with this purposive sampling, a relevant mix of supervisory experiences from the participants would be achieved.

D. Data collection

One-to-one semi-structured interviews were conducted by the PI using an interview guide (Appendix 1). The interview guide was developed by the PI with inputs from the research team. The interviews were audio-recorded with informed consent of the participants. Due attention was paid to the content of the participants’ sharing and the emerging themes during the interview and analysis process such that consideration of including more participants in the study would be taken if there was a need for further varied views to be elicited (Creswell, 2014).

E. Analysis

A qualitative research approach with thematic analysis was adopted. The Atlas Ti (version 8) software was used to code and analyse the data. Coding of all the data was made by the PI before a coding structure was created. There was a reiterative development and re-development of the coding structure such that all the data were appropriately accounted for. Codes were added and revised as more interviews were conducted. All the data were coded according to the study objectives and were classified into categories that reflected the emerging themes. Based on further readings in medical education literatures, the themes were grouped and sub-grouped in a logical fashion to form a thematic template. The raw data were revisited regularly throughout the analytic process to ascertain that the codes and resulting themes were grounded in the data. To ensure adequate coding and to improve the research reliability, we performed investigators’ triangulation. The co-investigator (LWS) was invited to analyse the first three interviews independently. The PI and co-investigators (TLL, VM, YHL) discussed regarding the main themes developed and differences were addressed and reconciled. To further improve credibility and transferability of the research data and its analysed results, member checking was used and participants’ comments regarding the developed themes were solicited. There was general agreement with the results generated from their interviews.

III. RESULTS

Six supervisors and six supervisees completed the study. As the research progressed, there was the progressive realisation of an overarching pattern emerging around the supervisory process, namely, the heterogeneity of the concept of supervision and the tension and conflicts amongst its various roles and functions.

Four major themes emerged:

- Meaning and definition of supervision

- Expectations and responsibilities

- Elusiveness of mentoring elements in educational supervision

- Personal and professional development in supervision

A. Meaning and Definition of Supervision

1) Supervisor’s perspectives: Supervisors defined supervision as “observing”, “helping”, “guiding”, “teaching”, “grading” and “assessing” the residents such that they could be certified to fulfil the program requirements. These descriptors suggested a supervisor-centric definition.

“Someone in a position of experience or age supervises, in other words…observe…teaches, impact knowledge and skills to the supervisee…is like watching somebody”

(S1)

2) Residents’ perspectives: Residents referred to supervision as an “apprenticeship”, “guiding and checking on progress” and promoting the “maturation as a clinician”. There was the repeated emphasis on the supervisor attending to the resident’s “growth”, “personal well-being” and to “encourage” and “commend”.

“…essentially is in line with the whole practice of medicine where there is apprenticeship, someone has to guide…to encourage, commend, growth…”

(R1)

B. Expectations and Responsibilities

1) Supervisor’s perspectives: Supervisors expected residents to be able to exhibit the attitude of being “able to talk about things and not being afraid of being judged”; “to pay attention to personal development so that the resident is more real as a person”; “to be ready to give feedback about supervision” and “being comfortable, open and trusting of the supervisor’s intentions”.

In practice, however, faculty observed that residents were “not expecting beyond helping them with clinical work”; “does not talk about struggles and frustrations” and were “not used to opening up”. Although engaging the resident with regards to their struggles was identified to be important, it was highlighted as “not the culture or consistently practiced” and that “residents may not appreciate why we want them to talk about their feelings”.

Faculty viewed discussing about resident’s personal issues as intrusive and a violation of the boundaries in supervision.

“We also have to keep some boundaries… we are careful not to go beyond certain boundary especially if it is something which the supervisee is not very comfortable with”

(S1)

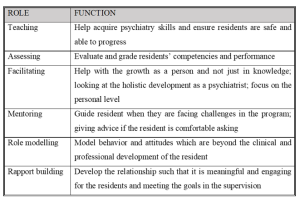

Table 1 illustrates our faculty’s understanding of the roles and functions of the educational supervisor.

Table 1: Faculty’s understanding of the roles and functions of the educational supervisor

2) Residents’ perspectives: Residents’ expected the educational supervisor to be “approachable and open”, “easy to talk to”, “relaxed”, “able to attend to personal growth”, “helping to reflect” and “build rapport”. Residents thus expected a more relational as opposed to transactional interaction with the supervisor.

“…apart from the bread and butter clinical aspects of work…talk to you a bit more about your personal stage in life, how things are coming along… It is this stuff that I find it hard to find in textbooks or anywhere along the clear training roadmap”

(R1)

Residents tended to see the educational supervisor’s role as conflictual in view of the attendant assessor function, and how boundaries between the two roles are often not clearly delineated.

“Ultimately is quite hierarchical in the system…. so if a supervisee has a lot of problems and come to the supervisor for advice…the supervisor might negatively evaluate the supervisee”

(R2)

C. Elusiveness of Mentoring Elements in Educational Supervision

1) Supervisor’s perspectives: Faculty viewed mentoring as “broader”, “longer term” and “beyond clinical and professional development”. “Trust” and “special” characterised a mentoring relationship but the focus was more on “professional development” rather than “personal development”. Faculty did not see themselves as fulfilling a mentoring role but generally agreed that there could be opportunities in offering elements of mentoring in educational supervision and to “contribute to the growth of residents beyond the short-term focus on clearing examinations”.

“…take about certain other aspects you know…mentorship if possible…beyond the pure clinical and professional development”

(S1)

Supervisors alluded to their roles in educational supervision as “facilitating the growth as a person”; “giving advice” and “role modelling” but they did not consider these as mentoring roles even though these were generally accepted as mentoring in nature.

“…never seen myself in a mentoring position…mentoring goes beyond just the supervisor-supervisee relationship…but I don’t think it has really extended beyond that”

(S3)

2) Residents’ perspectives: There was a similar reference to mentoring as “adopting a broader view of the development of the resident” over “a longer period of time”. Residents described mentoring as having a “deeper emotional connect” and “beyond the clinical development”. The evaluator role was viewed as potentially inhibiting the development of a mentoring relationship.

“So, it muddles the role…when they are so tied up to assess…they may not be able to mentor as much…”

(R1)

D. Personal and Professional Development of Residents

1) Supervisor’s perspectives: Professional development was referred to as the “professional attitudes and motivation”, “duty of care”, “ethical boundaries” and the attributes which are more “formal” as contrasted to personal development. The latter being referred to as “one’s character”, “temperament”, “personality”; “the way we see things”; “development of self-awareness and self-actualisation” and the “need to know yourself and what problems you have in order to be able to help your patients struggling with personal problems”. Faculty also referred to personal development as “developing as a person and handling of stress”, “how to handle complaints”, and “how to juggle various roles to have a work-life balance”. Other views of personal development included “extracurricular activities outside of psychiatry” and “some hobbies” which some faculty opined as “more important in psychiatry because of the importance for self-care”.

However, some faculty held the opposing view that personal development should not be the focus of educational supervision. Lapses in personal development would only be brought up during supervision if there were “negative effects on professional roles and clinical practice and impeding progress” for risk of being accused of “prying into the residents’ personal lives and being nosy”.

“…but I don’t focus so much unless they hinder the work side of things. But maybe we should…”

(S3)

The reluctance of some residents to discuss issues of personal development were interpreted as an “Asian thing”, for instance being “uncomfortable” talking about personal struggles and “residents not expecting it”’.

2) Residents’ perspectives: Residents’ referred to personal developmental aspects as “be as a person”, “religious growth”, “personal well-being”, “how you are getting on with life as a whole”, “finding out about the person’s preferences”, “strengths and weaknesses” and “outside of the career”.

There was the fear of the lack of confidentiality and of being evaluated negatively if residents were to portray themselves as having personal struggles.

“though resident want to grow and develop but exposing these shortcomings could be very sensitive…”

(R1)

Residents considered personal aspects of their development to be “more private”; “should not be covered unless interferes with professional development”; “not so important”; “not fair for the supervisee and supervisor” and “something you should sort out on your own”. They perceived supervision to be formal and mainly moments of assessment for their professional development and so it would be inappropriate to discuss about personal struggles. Some residents also held the view that “personal and professional lives are separate” and the “supervisor may not be interested”.

“…to say that the supervisor should cover personal growth I don’t think that is very fair as well”

(S4)

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Conceptualisation of Educational Supervision

The concept of educational supervision was alien to both residents and supervisors. Supervision was seen mainly as teaching the residents to acquire knowledge and clinical skills with a focus on the transactional aspects. Our residents preferred a more relational supervisory interaction. The finding of psychiatry trainees valuing a supervisor’s emotional supportiveness more highly than clinical competence was also reported in another study (Chur-Hansen & McLean, 2007).

Our results showed that roles of teaching and assessing were more consistently endorsed by the supervisors. Relational roles like facilitating, role modelling, rapport building, and mentoring were considered important but cited less frequently by both groups. Participants tended to attribute this to the training’s emphasis on evaluation and assessment such that the focus of the supervision was more on the transactional rather than the relational components. This might have resulted in tension within the supervisory relationship as expectations for assessment of competencies take precedence (Julyan, 2009). This phenomenon was both ironic and worrying as the original intention for setting up the supervisory framework in the psychiatry residency program was to ensure that the training and learning would be supplemented by the presence of an educational supervisor with a mentoring role, entrusted with the fostering of the personal and professional components in clinical supervision (Kilminster et al., 2007).

B. Assessor Role of Supervisors

Although residency assessments were mainly formative, residents in our study still harbored concerns about the supervisor fulfilling the assessor role and determining their readiness to progress. If assessments were to be perceived as high stake in our examination-oriented training environment, the role of the teacher as helper might be compromised (van der Vleuten et al., 2012). As highlighted by the data in our study, combining the roles of helper and judge could confront the supervisor with a conflict of interest (Cavalcanti & Detsky, 2011). There might be situations either of inflation of judgement (Govaerts et al., 2007) or trivialisation of the assessment process (Dudek et al., 2005), which would potentially impair the professional development of the residents.

C. Personal and Professional Development

There was a common reference by both faculty and residents to the growth of the resident. Based on our data, there appeared to be some overlap of the concept of personal and professional development of residents in psychiatry training. Supervisors viewed the ability to handle stress and developing resilience not only as aspects of personal development but a reflection of the professional competence as well. But supervisors also opined that within the current supervisory framework, they would not be able to support the personal development of the residents. Although residents indicated their desires for supervisors to facilitate their holistic development and growth towards becoming a psychiatrist, they did not expect supervisors to be interested in their personal development but to focus more on the professional development of their clinical competencies.

There was avoidance by supervisors and residents to discuss personal struggles and frustrations in our study. This would be of concern if in the context of educational supervision in psychiatry, the personal aspects and development of better self-awareness could not be achieved, bearing in mind that this had been considered by some to be the fundamental goal of supervision in counselling (Kadushin, 1985). Concerns of boundary violations within the supervision relationship were raised by both groups of participants. In our study, the supervisors’ strict adherence to the boundaries as accustomed to in psychotherapeutic practice might deter self-disclosure. In contrast, our data suggested that sharing of clinical experiences by their supervisors were very much welcomed by the residents. Research has shown that there might be improvement in alliance when supervisors disclosed relevant past clinical experiences (Matazzoni, 2008). Self-disclosure by the supervisor usually normalised clinical struggles experienced by the residents and could enhance the supervision relationship (Knox et al., 2011). In our study, supervisors held fairly rigid boundaries within supervision, which had been shown to hinder the development of authentic emotional relationships or deeper mentoring relationships (Kozlowski et al., 2013).

Supervisors in our study reflected that it might have been cultural or an ‘Asian thing’ for residents to avoid discussion of personal struggles. Eastern cultures were noted to appreciate a larger power distance than Western cultures (Hofstede, 2011). Cultural value theory also opined that Eastern cultures tended to be more conservative and hierarchical and valued mastery to a lesser extent than the West (Schwartz, 1999). In our predominantly Asian context, the perception of a hierarchical training system might result in supervisors maintaining a stricter teacher-student boundary, or residents being more reluctant to share personal frustrations, particularly with the more senior supervisors. The evaluator role of the supervisor might also result in the resident erecting certain boundaries in the supervisory relationship. This would have implications for nurturing the personal and professional growth of the residents, which require guidance through mentorship and self-reflection within a trusting relationship (Holden et al., 2015).

D. Psychological Safety Within a Trusting Supervisory Relationship

Previous research has shown that any feedback which invoked the self potentially carried with it social judgements which might threaten the educational alliance (Pugh & Regehr, 2016; Telio et al., 2015) and there was a tendency for both supervisors and supervisees to interpret performance assessments as part of a judgement of personal worth (Hawe, 2003). The psychological safety within the supervisory relationship would be particularly important as awareness of the residents’ own inadequacies might be unpleasant and threatening as they faced their imperfect understanding and subjective theories (Vec et al., 2014). As such, the goals of supervision would be best attained with a trusting supervisor-supervisee relationship. However, our study showed that residents are unwilling to reveal too much of their inadequacies as this was too threatening for them, considering that their supervisors also evaluated their overall work performance and ability to deal with stress. This had resulted in tension in the supervisory relationship. The failure to pay heed to this, whether it was inherent to the training program or secondary to the supervisors’ lack of awareness, might further hinder and jeopardise the supervisory process.

The tension between assessment for support and assessment for high stakes decision-making will continue to challenge supervisors. The conflict between mentoring and appraisal of competency would need to be addressed. It would be important for residency training programs to create opportunities to allow the fostering of trusting supervisory relationships. Roles and expectations of the educational supervisor would need to be articulated clearly to both supervisors and residents. Supervisor training would need to focus not only on supervisor ability and competencies but more importantly, supervisor motivation. There should be the emphasis on instilling awareness of internal values and beliefs encompassing competency assessment, accountability, potential role conflicts, feedback delivery and “skills for establishing trusting, open and non-defensive yet problem–confronting relationships” (Govaerts et al., 2007).

E. Limitations of the Study

In our study, newly graduated residents who were agreeable to participate were recruited. The views of the ‘unwilling’ participants regarding supervision which might be more diverse and contentious might be inadvertently excluded. The content of the interview guide used was also not validated. Another limitation concerned the dual roles of researcher and APD. The view of the resident group might be subjected to biases and undue influence due to power differentials (Kotter, 2010). The researcher had minimised such potential biases by being reflexive and addressed concerns of imposing on the participants’ views openly during the interview (Creswell & Miller, 2000).

V. CONCLUSION

The mentoring role in supervision was found to be lacking in our current residency training. The residency program structure, with its focus on assessments of competencies and examinations, might have the unintended consequences of encouraging a transactional supervisory structure at the expense of a relational and mentoring relationship. This qualitative study highlighted significant differences in definitions, roles and expectations of educational supervision. It was our intention that this research endeavor contribute towards better appreciation of the dynamics within educational supervision in a competency-based residency training framework and further inform developments in the mentoring component of supervisory practices in the other training programs as well.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Lay Ling Tan formulated the research question and designed the research methodology. She conducted the semi-structured interviews and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

Prof Pim W. Teunissen provided guidance for the research methodology and data analysis. He was also involved with the revision of the manuscript drafts.

Dr Wee Shiong Lim provided guidance for the research methodology, assisted with the initial analysis of the first three interviews independently as well as the revision of the manuscript drafts.

Both Dr Vanessa Wai Ling Mok and Dr Hwa Ling Yap were involved with recruitment of participants and data analysis.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was sought from the Institutional Review Board (CIRB Ref: 2017/2319) and informed consent was received from all participants.

Data Availability

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the National Psychiatry Residency Program Supervisors and Residents for their willingness to participate.

Funding

We did not receive any funding for this research study.

Declaration of Interest

Dr Lay Ling Tan is the Associate Program Director and the PI of this research. Dr Hwa Ling Yap and Dr Vanessa Mok are both teaching faculty of the teaching site. They have a vested interest in ensuring the quality of supervision of residents. The other authors have no other conflicts of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

Akhtar, S. (2009). Comprehensive dictionary of psychoanalysis. Routledge.

Carroll, M. (2006). Counselling supervision: Theory, skills and practice. SAGE.

Cavalcanti, R. B., & Detsky, A. S. (2011). The education and training of future physicians: Why coaches can’t be judges. JAMA, 306(9), 993-994. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1232

Chay, O. M. (2019). Transformation of medical education over the years – A personal view. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 4(1), 59–61. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2019-4-1/PV1076

Chur-Hansen, A., & McLean, S. (2007). Trainee psychiatrists’ views about their supervisors and supervision. Australasian Psychiatry, 15(4), 269-272.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.

Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into practice, 39(3), 124-130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Driessen, E. W., Overeem, K., & van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2011). Get yourself a mentor. Medical Education, 45(5), 438-439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03948.x

Dudek, N. L., Marks, M. B., & Regehr, G. (2005). Failure to fail: The perspectives of clinical supervisors. Academic Medicine, 80(10), S84-S87.

Falender, C. A., & Shafranske, E. P. (2007). Competence in competency-based supervision practice: Construct and application. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38(3), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.3.232

Frank, J. R., Snell, L., Englander, R., & Holmboe, E. S. (2017). Implementing competency-based medical education: Moving forward. Medical Teacher, 39(6), 568–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2017.1315069.

Govaerts, M. J., van der Vleuten, C. P., Schuwirth, L. W., & Muijtjens, A. M. (2007). Broadening perspectives on clinical performance assessment: rethinking the nature of in-training assessment. Advances in Health Sciences Education Theory Practical, 12(2), 239-260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-006-9043-1

Hansman, C. A. (2001). Mentoring as continuing professional education. Adult learning, 12(1), 7–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/104515950101200104

Hawe, E. (2003). “It’s Pretty Difficult to Fail”: The reluctance of lecturers to award a failing grade. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(4), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293032000066209

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Holden, M. D., Buck, E., Luk, J., Ambriz, F., Boisaubin, E. V., Clark, M. A., Mihalic, A. P., Sadler, J. Z., Sapire, K. J., Spike, J. P., Vince, A., & Dalrymple, J. L. (2015). Professional identity formation: Creating a longitudinal framework through TIME (Transformation in Medical Education). Academic Medicine, 90(6), 761–767. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000719

Julyan, T. E. (2009). Educational supervision and the impact of workplace-based assessments: a survey of psychiatry trainees and their supervisors. BMC Medical Education, 9(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-9-51

Kadushin, A. (1985). Supervision in social work. Columbia University Press.

Kilminster, S., Cottrell, D., Grant, J., & Jolly, B. (2007). AMEE Guide No. 27: Effective educational and clinical supervision. Medical Teacher, 29(1), 2–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701210907

Knox, S., Edwards, L. M., Hess, S. A., & Hill, C. E. (2011). Supervisor self-disclosure: Supervisees’ experiences and perspectives. Psychotherapy, 48(4), 336–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022067

Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (2nd ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. (Original work published 1984).

Kotter, J. P. (2010). Power and influence. Simon and Schuster.

Kozlowski, J. M., Pruitt, N. T., DeWalt, T. A., & Knox, S. (2013). Can boundary crossings in clinical supervision be beneficial? Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 27(2), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2013.870123

Launer, J. (2013). Supervision, mentoring and coaching. In Swanwick. T (Ed.), Understanding medical education. Evidence, theory and practice (2nd ed., pp 111-122). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118472361.ch8

MacDonald, J. (2002). Clinical supervision: A review of underlying concepts and developments. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(1), 92-98. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.00974.x

Matazzoni, T. A. (2008). The influence of supervisor self-disclosure on the supervisory working alliance in beginning and advanced therapists-in-training [Doctoral dissertation]. ProQuest.

Passi, V. (2016). The importance of mentoring during educational supervision. Perspectives on Medical Education, 5, 195-196.

Patel, P. (2016). An evaluation of the current patterns and practices of educational supervision in postgraduate medical education in the UK. Perspectives on Medical Education, 5(4), 205-214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-016-0280-6

Pront, L., Gillham, D., & Schuwirth, L. W. (2016). Competencies to enable learning-focused clinical supervision: a thematic analysis of the literature. Medical Education, 50(4), 485–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12854

Pugh, D., & Regehr, G. (2016). Taking the sting out of assessment: is there a role for progress testing? Medical Education, 50(7), 721-729.

Schon, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching learning in the professions. John Wiley.

Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied psychology, 48(1), 23-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1999.tb00047.x

Tebes, J. K., Matlin, S. L., Migdole, S. J., Farkas, M. S., Money, R. W., Shulman, L., & Hoge, M. A. (2011). Providing competency training to clinical supervisors through an international supervision approach. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(2), 190-199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731510385827

Telio, S., Ajjawi, R., & Regehr, G. (2015). The “educational alliance” as a framework for reconceptualizing feedback in medical education. Academic Medicine, 90(5), 609-614. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000560

Torby, A., Turner, M. B., Kinzie, J. M., & Usher, C. (2015). What we talk about when we talk about supervision: The clear and the confusing in graduate psychiatric education. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 63(5), NP7-NP12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065115609724

van der Vleuten, C. P. M., Schuwirth, L. W. T., Driessen, E. W., Dijkstra, J., Tigelaar, D., Baartman, L. K. J., & van Tartwijk, J. (2012). A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Medical Teacher, 34(3), 205-214. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.652239

Vec, T., Rupnik Vec, T., & Žorga, S. (2014). Understanding how supervision works and what it can achieve. In Watkins C. E. &. Milne D. I (Eds.) The Wiley International Handbook of Clinical Supervision (pp 103-127). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118846360.ch5

Wald, H. S. (2015). Professional identity (trans) formation in medical education: Reflection, relationship, resilience. Academic Medicine, 90(6), 701-706.

*Lay Ling Tan

2 Simei Street 3 S529889

Email: tan.lay.ling@singhealth.com.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.