Humanism in Asian medical education – A scoping review

Submitted: 1 March 2021

Accepted: 13 September 2021

Published online: 4 January, TAPS 2022, 7(1), 9-20

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-1/RA2460

Cindy Shiqi Zhu1, Ryan Kye Feng Yap2,3, Samuel Yong Siang Lim2,3, Ying Pin Toh2,4 & Victor Weng Keong Loh1,2

1Department of Family Medicine, National University Health System, Singapore; 2Division of Family Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 3Ministry of Health Holdings, Singapore; 4HCA Hospice, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Humanistic values lie at the heart of medicine. In the wake of professional breaches among health care professionals, the place of humanistic values in medical training has been the subject of much debate and development in the literature. This scoping review aims to map the current understanding of how humanism in the Asian socio-cultural context may be understood and applied, and how the strengthening of humanistic values may be further integrated into medical schools in Asia.

Methods: Arksey and O’Malley’s approach to scoping reviews was used to guide the study protocol. Databases PubMed, ERIC, EMBASE, Scopus, CINAHL, and Web of Science were searched for articles on humanism and medical education in Asia. Data charting and thematic analysis were performed on the final articles selected.

Results: Three hundred and six abstracts were retrieved, 93 full-text articles were analysed, and 48 articles were selected. Thematic analysis revealed four themes on the need to strengthen humanistic values, the challenge of finding a common framework and definition, opportunities in medical school for curriculum design and training, and the need for validated tools in program evaluation in Asia.

Conclusion: Themes highlighted in this review show an increasing recognition amongst Asian medical educators of the importance of inculcating humanistic values into medical training. Further research and ongoing discussion are needed to develop culturally relevant, effective, and integrative curricula in order to promote humanistic attitudes and behaviours among medical students and physicians in Asia.

Keywords: Humanism, Asia, Medical Education, Medical Students, Admission, Curriculum, Mentorship, Assessment, Medical Humanities, Humanistic Values

Practice Highlights

- This review maps how medical schools in Asia impart humanistic values.

- There is a pressing need to strengthen humanistic values among medical students in Asia.

- The outcomes of current strategies are varied; mentorship and reflection on experience are crucial.

- There is much scope for further research in culturally relevant pedagogy that may impart humanism.

- Validated tools need to be developed for evaluating interventions to impart humanism in healthcare.

I. INTRODUCTION

Humanistic values lie at the heart of medicine. Humanism in health care has been defined as “an intrinsic set of deep-seated convictions about one’s obligations toward others”, and “devotion to human welfare”, characterised by a respectful and compassionate relationship between physicians, their patients, and other members of the healthcare team (Cohen, 2007; Gold, 2018).

Recent increased interest in the development of humanism in medical education (Maheux et al., 2000; Moyer et al., 2010; Wald et al., 2015) may be in response to concerns regarding the erosion of humanistic qualities among medical professionals (Haque & Waytz, 2012; Thibault, 2019). The push for medical humanism gained momentum through various advocacy movements, such as the Arnold P. Gold foundation in the United States, where the ‘IECARES’ framework was created to facilitate systematic discourse and study of humanism (Gold, 2018).

Medical educators in Asia have long recognised that humanistic traits are key to the art of medicine. They recognise that humanistic values have a positive effect on the patient-physician relationship, correlate positively with patient satisfaction, positively influence treatment outcome and adherence, and help maintain harmony in the working environment (Asai et al., 2007; Chiu et al., 2009; Saw, 2018; Song et al., 2017; Tokuda et al., 2008). Training in humanistic attitudes may therefore provide ballast to the thorny relationships sometimes seen in medical practice. In China, for example, more than 70% of doctors have experienced medical violence in hospitals, and strengthening humanistic values during medical training has been proposed as an urgent and important strategy to counteract this phenomenon (Hu, 2016).

Published studies from Asian medical training contexts that examine the perception, pedagogy, and assessment of humanistic values, and how humanism education frameworks derived from Western sociocultural contexts resonate with the cultural values, social history, and healthcare infrastructure in Asia are however relatively scarce.

As a social construct (Cohen, 2007; Kelly & Dornan, 2016; Rios, 2016), the discourse on humanism in Asian medical education and medical practice must consider cultural and contextual distinction from the main body of current literature that stems mainly from the West (Claramita et al., 2013; Schouten & Meeuwesen, 2006; Tsai, 2001). This study aims to explore how humanism has been understood and applied in medical education in the Asian sociocultural context by scoping current knowledge and evidence.

II. METHODS

A preliminary literature review revealed that existing literature on humanism in medical education in Asia was heterogeneous and limited. As such, a scoping review methodology was selected (Thomas et al., 2017). Arksey and O’Malley’s approach to scoping reviews was used to guide the study protocol (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Ethics approval was not required for this study, as it does not involve human subjects or data.

A. Identifying the Research Question and Relevant Studies

This study aims to provide an overview of the current knowledge on humanism in Asian medical education, identify successes and deficiencies in current practice, and guide further research.

The PICOS format was used to structure the research question for the literature search (Table 1). While alternate frameworks of humanism such as the Interactive Heart and Head model (Montgomery et al., 2017) and the outcome-oriented approach (Ferry-Danini, 2018) were considered, the authors decided that the Gold Foundation’s IECARES framework which knit together different strands of the humanism construct into a meaningful cohesive unit was most suited as a scaffold for our search terms. We thus included studies of any design on humanism and its core characteristics (Integrity, Excellence, Compassion & Collaboration, Altruism, Respect & Resilience, Empathy, and Service) as defined by the Gold Foundation’s IECARES framework), among medical students and educators in Asia. We excluded articles in foreign languages, on non-Asian populations, and allied health professionals (e.g. dentistry, pharmacy, nursing students). The search strategy was formulated through discussions between the authors and a medical librarian (A.C). Comprehensive search terms were constructed to expansively identify studies containing any synonyms or variation of three key concepts: humanism, medical education, and Asian countries and regions as defined by the United Nations Statistical Division (United Nations Statistics Division, n.d.). Six databases – PubMed, ERIC, EMBASE, Scopus, CINAHL, and Web of Science were searched.

|

PICOS Table |

Inclusion Criteria |

Exclusion Criteria |

|

Population |

Medical students and practising physicians including residents in Asia |

Allied health specialities such as nursing, pharmacy and physiotherapy. Non-medical specialities such as dentistry. Studies from non-Asian countries and regions |

|

Intervention |

Studies on humanism and its core characteristics (integrity, excellence, compassion, altruism, respect, empathy, and service) as defined by the GOLD foundation |

|

|

Comparison |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Outcome |

Definition of humanism Similarities and differences between Asian and Western concepts of humanism Perceptions on the integration of humanism as a subject/concept in medical education Methods of teaching humanism Assessment of humanistic characteristics and behaviour Suggested time point in training for teaching humanism |

|

|

Study Design |

All study designs and article types were included (observation studies, cross-sectional studies, nominal group studies, Delphi study, literature review, and scoping review) |

Studies published in a non-English language |

Table 1: PICOS Table of Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

B. Study Selection

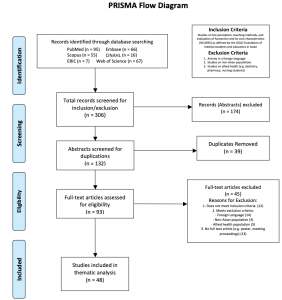

The selection process for articles is summarised in the PRISMA format (Moher et al., 2015) in Figure 1. Three hundred and six abstracts were identified through the initial search and reviewed after the removal of duplicates. Ninety-three full-text articles were examined to determine suitability for inclusion according to the selection criteria. Forty-eight full-text articles were included in the final review for thematic analysis.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flowchart

C. Data Charting

Braun and Clarke’s inductive approach to reflective thematic analysis was utilised (Braun & Clarke, 2013, pp. 248-273). Two researchers (CZ and RY) independently reviewed the studies. Articles were read and analysed in detail, and key ideas were recorded into a data abstraction coding sheet (Zhu et al., 2021a). Frequently discussed ideas were identified and generated into a list of initial themes, which were added to a data extraction form (Zhu et al., 2021b). The researchers iteratively reviewed the independently extracted themes for agreement. This entailed a familiarisation with the depth and breadth of current knowledge through literature review and immersion in the derived data. The researchers subsequently ensured consistency in data extraction by applying the same coding sheet and data extraction forms on the entire data set, forming a template that included all the key ideas that were coded. Sessions for peer debriefing were set up to discuss more complex ideas by discussing each researchers’ interpretation all the while ensuring relevance to the research question.

D. Collating, Summarising, and Reporting Results

Codes and initial themes from the data abstraction sheet were reviewed and summarised into four final themes based on semantic and conceptual similarity. The themes were refined during the abstraction phase, and multiple discussions were conducted amongst all authors to achieve consensus on their definition and content. The results are reported in figures and narrative form below.

III. RESULTS

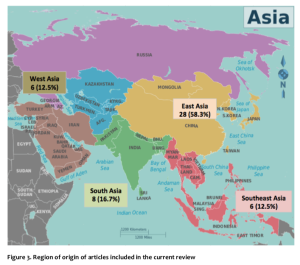

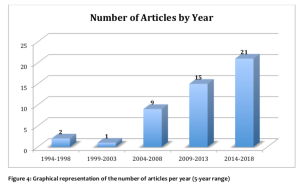

The final articles included in this review consisted mainly of cross-sectional studies of survey-based quantitative or mixed-method design and commentaries/essays by medical educators. There were a smaller number of nominal group studies, literature reviews, one Delphi study, and one scoping review on medical professionalism (Figure 2). East Asian studies (China, Taiwan, Japan, and Korea) comprised 58.33% of the articles included, South Asian (India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh) studies accounted for 16.7%, while studies from West Asia (Israel, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia) and Southeast Asia (Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand) each accounted for 12.5% (Figure 3). The articles ranged in publication date from 1995 to 2018. Notably, there was a steady increase in the number of articles over this period (Figure 4). Thematic analysis revealed the following themes on humanism in Asian medical education (Zhu et al., 2021a, 2021b).

Figure 2. Graphical representation of article types included in the current review

Figure 3. Region of origin of articles included in the current review

A. Training in Humanistic Values: A Pressing Need in Asian Medical Schools

The common refrain of concern for the current state of medical students’ and physicians’ humanistic qualities was highlighted in many articles from several Asian countries and regions. Issues related to breaches of professional and ethical behaviour among medical students and young physicians were widespread and of serious concern to medical educators and the general public in Japan (Tokuda et al., 2008). Taiwanese educators lamented a lack of dedication and personal commitment among young Taiwanese physicians compared to their predecessors (Chiu et al., 2010). In Pakistan, concerns regarding the deterioration of humanism and professional values in medicine were raised, with students overestimating the self-rated quality of their bedside manner compared to objective assessments (Farooq et al., 2013). Bhatia et al from India indicated that humanistic traits such as empathy, caring, altruism, and compassion were often underdeveloped in medical students and doctors (Bhatia et al., 2013). In China, medical students were described to be lacking in humanistic concerns, humanistic knowledge (cultural, geographical, historical), and awareness of the importance of humanism education (Liu & Li, 2012). A cross-sectional study of emergency physicians in Singapore found that they were perceived to be weak in humanistic traits including patient communication, holistic management, and professional relationship with colleagues (Fones et al., 1998). There was a clear and pressing need to foster humanistic values in medical training in Asian medical schools (Asai et al., 2007; Chiu et al., 2009; Hu, 2016; Saw, 2018; Song et al., 2017; Tokuda et al., 2008).

B. “Seeking the Welfare of the Other”: Unity Amidst Diversity of Meanings of Humanistic Values

Studies on Asian medical humanism adopted definitions and frameworks from the West, such as the Gold Foundation’s IECARES framework, and ABIM’s charter of physician professionalism (Chiu et al., 2009; Tsai et al., 2007). However, the direct application of these definitions and frameworks in Asia has been questioned (Chiu et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2016){Chiu, 2009 #53}. It has been recognised that the interpretations of medical humanism may vary due to the influence of local cultural, religious and philosophical systems, as well as difficulties in translating abstract concepts such as “ethics” that have been derived from a Western context (Ho et al., 2014; Pan et al., 2013; Qian et al., 2018; Zhang & Cheng, 2000).

While Western notions of humanism dichotomised physicians’ professional and personal lives, studies found that the collectivism imbued in East Asian physicians underpinned by Confucian cultural traditions blurred the lines between one’s personal and societal roles (Ho et al., 2014). Pan et al. (2013) commented that healthcare professionals in China considered the Western-derived term of “ethics” as being external to the individual, and thus ranked it low on the list of desired professional values in deference to “moral character” which was perceived to be more innate. The Confucian collectivistic slant could further be gleaned in concepts such as guanxi – the fostering of social relationships through the mutual exchange of favours, renai – “humane love” and gongxin or “public-spiritedness”. Traditional Chinese medical ethics, while influenced by two other major traditions – Taoism which leaned toward the pursuit of longevity, and Buddhism whose goal was the transcendence of the endless cycles of rebirth through non-attachment and garnering of merit, nonetheless had Confucianism as its core position (Zhang & Cheng, 2000).

While Jiang and Liu from mainland China proposed a narrative definition of humanistic medicine as “an interdisciplinary science that synthesizes knowledge concerning medical philosophy, medical ethics, medical law, medical history, medical sociology, medical logic, and doctor-patient communication” (Jiang & Liu, 2014), Wong from Taiwan has proposed the same to be “[a service environment where] patient welfare, patient autonomy, and social justice take primacy, and [practitioners] offer charitable and dignified treatment” (Wong et al., 2012). Among Asians of the Muslim tradition, Al-Eraky et al. (2014) described a four-gates model that pointed to four relationships the Muslim-Arab medical professional did well to align him/herself with; these include right relationships with the self – self-awareness, with the task-at-hand – excellence and reflective practice, with others – respect of patients and team members, and with God – self-awareness and right relationship with the Divine (Al-Eraky et al., 2014). Meanwhile, the perspective of patients in Singapore and Israel while highlighting the importance of moral-humanistic traits such as empathy highly, nonetheless ranked professional expertise above all other traits (Fones et al., 1998; Schattner et al., 2004).

Amid the broad differences in individual differences in how humanistic values were articulated regionally – for instance, the reference to collectivism in the East Asian context, and the reference to the divine in the Arab-Muslim context – these expressed how each sociocultural context sought that common humanistic goal of “seeking the welfare of the other.” We propose that the universal attributes of the IECARES framework (Gold, 2018) arguably encompasses these values.

C. Humanistic Values in Medical Training

1) Select for humanistic values:

For medical admissions to successfully select candidates that would become humanistic and competent medical professionals at the end of training, any process for entry into medical school based narrowly on academic criteria was inadequate. Authors argued that in addition to academic performance, medical admissions processes should include involvement in community work, extra-curricular activities, and the consideration of recommendation letters to better reflect the humanistic attributes of candidates that academic performance alone would not capture (Chiu et al., 2009; Lee & Ahn, 2004; Tokuda et al., 2008)

2) An afterthought in planning:

As a non-traditional curricular item, the introduction of humanism learning activities into already heavily packed curricula would often be met with resistance and/or inertia, be ranked lower in priority (Rao & Rao, 2007; Tokuda et al., 2008) and thereby poorly integrated into Asian medical school curricula (Liu & Li, 2012; Rao & Rao, 2007). When these existed in the curriculum, humanism courses were usually of short duration, offered as an elective (Liu & Li, 2012; Qian et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2016), and scheduled at unfavourable time slots (Kosik et al., 2014; Notzer et al., 2005). Students were often hard-to-manage and poorly motivated (Tsai et al., 2007; Woratanarat, 2014), and faculty would often have variable credentials (Liu & Li, 2012). Compounding this was the common experience of observing humanistic values being sidelined by busy healthcare providers on entering the workforce (Tsai et al., 2007).

Caught where holistic care is valued. Humanistic values would be best caught in specialities that prioritised the holistic care of individuals and families such as Family Medicine. Authors lamented how paternalistic medical cultures (Farooq et al., 2013) prioritised the draw of cutting-edge technologies and hospital specialities in the curriculum (Akhund et al., 2014) over disciplines where humanistic biopsychosocial (Engel, 1977) care was explicitly valued (Biderman, 2003; Iqbal, 2010; Rao & Rao, 2007).

3) Begin early, continue longitudinally:

Asian medical educators generally agreed that learning humanistic values should start early, and continue into post-graduate education, with contextualisation of how these could be applied at different workplace settings (Biderman, 2003; Karunakaran et al., 2017; Kosik et al., 2014; Qian et al., 2018; Singh & Talwar, 2013; Wang et al., 2016). The Medical Council of India recommended that humanistic values be introduced in the early pre-clinical years to students who often harboured ideals and a sense of duty to their home communities before these sentiments waned with further training (Karunakaran et al., 2017). These learning opportunities should then extend longitudinally into post-graduate years when values may be challenged in the face of real-world challenges in clinical practice (Biderman, 2003; Singh & Talwar, 2013; Wang et al., 2016).

4) Learning methods: Experiences and reflection:

A range of teaching methods has been tried in the attempt to impart humanistic values in Asia. In addition to lecture-based learning, it was recommended that interactive experiential learning activities where humanistic attributes were practised should be designed into the curriculum (Wang et al., 2016). The Silent Mentor Program where students met and interacted with the families of human cadaver donors, listened to their narratives, and respectfully participated in culturally and religiously appropriate ceremonies, was an example of a successful program where students learnt to integrate humanistic values as they learnt about human anatomy (Karunakaran et al., 2017; Rao & Rao, 2007; Saw, 2018). Other teaching activities include the use of art in Hong Kong to prompt self-awareness and empathy (Potash & Chen, 2014), the use of film and photography (Kosik et al., 2014; Lee & Ahn, 2004; Nakayama, 2009; Woratanarat, 2014), and training in communications skills that integrated interpersonal- and clinical- skills training (Biderman, 2003; Kaga & Asakage, 2007; Yazigi et al., 2006), narrative medicine (Chiu et al., 2009) and community humanitarian work (Chen & Chou, 2015; Wang et al., 2016). Courses in the humanities and social sciences, such as history, literature, ethics, law, and medical social studies have also become part of some medical curricula; they provide insight into the human condition and have been successfully used to foster humanistic qualities in medical students (Fones et al., 1998; Lee & Ahn, 2004; Liu & Li, 2012; Song & Tang, 2017). The co-design and co-facilitation of medical humanities course of home-faculty based basic scientists or clinicians with social scientist colleagues as opposed to having social scientists running a programme solo was a promising curriculum strategy that legitimised and contextualised the importance of learning the medical humanities (Rider et al., 2014; Singh & Talwar, 2013).

5) Mentorship and role-modelling crucial:

Fostering strong and dedicated mentor-mentee relationships is crucial for the development of humanistic traits through positive role-modeling (Bhatia et al., 2013; Islam et al., 2014). Positive attributes in mentors motivated learners to model their humanistic behaviour (Bhatia et al., 2013; Chiu et al., 2009; Farooq et al., 2013; Islam et al., 2014; Singh & Talwar, 2013), whereas negative behaviours in the informal and hidden curriculum constituted a formidable counter-influence (Akhund et al., 2014; Salam et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2012). Authors highlighted the importance of faculty development where faculty learnt to internalise their responsibility as role models; strengthened awareness of their learner’s needs, expectations, and feelings; and recognised how as mentors they unwittingly enabled or hindered the positive development of humanistic attitudes among learners (Biderman, 2003; Liu & Cheng, 2017; Notzer et al., 2005; Rao & Rao, 2007).

D. Program Evaluation: Need for Validated Tools

A small number of articles in this review examined how humanism was evaluated in Asian medical schools. Most used self-assessment tools developed in Western contexts. For example, the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE) has been validated in several Asian cultures and languages and has a version for medical students (Mostafa et al., 2014). Taiwanese educators have translated and applied a 32-item self-administered questionnaire reflecting students’ perception of seven characteristics of professionalism defined by the American Board of Internal Medicine, many of which overlap with humanistic traits (Tsai et al., 2007). A novel instrument to measure students’ perception of personal attributes including honesty, respectfulness, and compassion was developed and validated by Malaysian educators, which included both a Likert scale and open-ended questions (Salam et al., 2012).

Few observer-rated and arguably more objective methods of humanistic behaviours were identified in this review. In a limited number of studies, the 360-degree peer evaluation was well received for evaluation of humanistic skills among physician trainees and residents (Tham, 2007; Wang et al., 2016), whereas the Defining Issues Test (DIT) may be a better tool for medical students with little working experience (Wang et al., 2016).

The need to develop validated methods to assess humanistic attributes was recognised, both to evaluate the effectiveness of teaching at the programmatic level (Tsai et al., 2007), as well as to identify students who required remediation and guidance in their professional development (Liu & Cheng, 2017).

IV. DISCUSSION

The current article presents a scoping review of peer-reviewed publications on humanism in Asian medical education. The four themes identified include the need to strengthen humanistic values among Asian medical students and physicians; the challenge of finding a common conceptual framework for operationalising humanistic values in Asia; opportunities in medical school to foster humanistic values at admissions, in curriculum planning, implementation within disciplines which teach holistic care, the use of different pedagogies, the role of mentorship, and fourthly the need for validated tools in program evaluation.

This review encompassed a diversity of types of articles and broad geographical representation.

Several findings of this review resonate with international literature. Both Western and Asian literature highlighted the importance of imparting humanistic values in medical training (Bombeke et al., 2010; Rios, 2016; Wald et al., 2015).

There was a lack of a common definition of humanistic medicine in this review, and that it was often conflated with other education concepts such as professionalism (Cohen, 2007; Hauck et al., 1990; Thibault, 2019; Tsai et al., 2007). We found nonetheless that the Gold foundation’s IECARES framework provided a broad enough scaffold to encompass the key notions of humanistic values in the Asian context. One of the key discrepancies between Asian and Western notions of humanism that surfaced in this review was that while humanistic medicine in the Western context often referred to a set of physician attributes, most commonly compassion, respect, and empathy toward patients, the therapeutic relationship in Asia may have distinct priorities. This would include the role of the patient in relation to his/her family, community, and society given the more collectivistic stance of the Asian patient. In addition, the notion of physician expertise may need to be more explicitly articulated (Fones et al., 1998; Ho et al., 2014; Schattner et al., 2004). In addition, the notion of relationship with self and the divine was highlighted in the West Asian four doors framework that is not explicitly mentioned in IECARES.

Much like educators in the West, Asian educators in this review describe the challenges associated with teaching humanism alongside the existing rigorous medical curricula for acquiring scientific and clinical skills, which often overshadows the humanistic aspect of medical education (Doran, 1983; Mostafa et al., 2014; Singh & Talwar, 2013). Nevertheless, some of the current methods used to impart humanism in Asian medical schools show promise in improving students’ humanistic attitudes. For example, medical-themed films were rated highly by students in their ability to enable understanding of humanistic and social aspects of medicine (Lee & Ahn, 2004), art-mediate learning increased students’ empathy on the State Empathy Scale (Potash & Chen, 2014), and the Silent Mentor Program nurtured the sense of responsibility and compassion within students as shown in their personal reflections (Lin et al., 2009). It remains a challenge for both Asian and Western medical educators to develop tools to objectively evaluate humanistic attitudes and behaviours (Buck et al., 2015; Shrank et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2016), which would be valuable in both assessing the effectiveness of teaching methods as well as motivate trainees to foster an active learning attitude (Pacifico et al., 2020).

Furthermore, methods to impart humanism must evolve along with students’ level of medical training. A qualitative study conducted in Singaporean found that medical trainees at different stages of their training valued different types of teachers, preferring a didactic approach in their earlier years, in contrast to more role-modelling and feedback once they step into clinical practice (Ooi et al., 2021).

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the term “humanism” and its conjugations were used in our search strategy to identify articles on humanistic attitudes and behaviours as a collective concept rather than its parts. However, there may be articles focused on one or more aspects of humanism education, such as empathy or compassion alone, which may not have been identified in the search. Furthermore, the inclusion criteria were constructed using Gold Foundation’s ‘IECARES’ framework, while it was later revealed through inductive thematic analysis that culturally relevant definitions should be developed to explore humanism in Asian medical education. Secondly, only English language databases were searched, and foreign language articles were excluded for practical purposes. Thirdly, there were notable intra-continental differences between various Asian countries represented, and there were a larger proportion of articles from East Asia in this review with Confucianism-based cultural origins. As such, conclusions drawn from these regions may be internally similar but require further adaptation for regions with differing religious or cultural origins.

V. CONCLUSION

Though Asia has been the cradle of many humanistic traditions since the dawn of civilisation, the explicit introduction of humanism education into the discourse of Asian medical schools is a recent phenomenon. This scoping review unveiled themes on key contentions around why, when, and how humanism should be integrated into the curriculum, and how this may impact the professional development of students, physicians and their relationship with their patients. Many of these topics are exciting areas of research that deserves greater attention.

Culturally validated frameworks and definitions of Asian medical humanism are lacking, and the agreed-upon frameworks may need to consider the sociocultural contexts of the different regions. What is clearly agreed upon is that the humanistic qualities of Asian medical students and physicians are in pressing need of improvement. Progress has been stifled by a slow start, the inertia from existing traditions that constrain changes, and differing opinions regarding the need for change. Various approaches to teaching humanism have been devised, such as elective humanities courses, participatory learning, mentorship, and the hidden curriculum. Authors called for improved quantity and quality of humanities courses, learning experiences outside of the classroom, and positive role-modeling in a longitudinal manner with constant integration back to the learner’s evolving clinical setting.

The current review presents an exciting growing body of literature advocating for the development of medical humanism in Asia. Further research, especially longitudinal studies, is needed to evaluate medical school admission processes, teaching and evaluation strategies in the instillation of humanistic medicine in Asia.

Notes on Contributors

TYP and VL designed and conceived the study. CZ and SL constructed search terms. CZ and RY conducted the literature review. CZ wrote the draft of the manuscript. CZ and VL co-edited the final draft. All authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval is not application for this review, as it does not involve human subjects or data.

Data Availability

The manuscript’s data is available at Figshare and may be accessed via the following public digital object identifier:

- Coding Sheet https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14245850.v1

- Data Abstraction Sheet https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14245991.v1

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Ms. Annelissa Chin Mien Chew for her assistance with search terms and database search.

Funding

This research received no specific grant or funding from any agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with any organisation or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

References

Akhund, S., Shaikh, Z. A., & Ali, S. A. (2014). Attitudes of Pakistani and Pakistani heritage medical students regarding professionalism at a medical college in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Research Notes, 7, 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-150

Al-Eraky, M. M., Donkers, J., Wajid, G., & van Merrienboer, J. J. G. (2014). A Delphi study of medical professionalism in Arabian countries: The Four-Gates model. Medical Teacher, 36 (Suppl 1), S8-S16. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.886013

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Asai, A., Ohnishi, M., Bito, S., Furutani, N., Ino, T., Kimura, K., Imura, H., Hayashi, A., & Fukui, T. (2007). Humanistic qualities of physicians: A view of Japanese residents. Medical Teacher, 29(4), 414. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701288523

Bhatia, A., Singh, N., & Dhaliwal, U. (2013). Mentoring for first year medical students: Humanising medical education. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 10(2), 100-103. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2013.030

Biderman, A. (2003). Family medicine as a frame for humanized medicine in education and clinical practice. Public Health Reviews, 31(1), 23-26.

Bombeke, K., Symons, L., Debaene, L., De Winter, B., Schol, S., & Van Royen, P. (2010). Help, I’m losing patient-centredness! Experiences of medical students and their teachers. Medical Education, 44(7), 662-673. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03627.x

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

Buck, E., Holden, M., & Szauter, K. (2015). A methodological review of the assessment of humanism in medical students. Academic Medicine, 90(11 Suppl), S14-S23. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000910

Chen, S.-S., & Chou, P. (2015). The implication of integrated training program for medical history education. Biomedical Journal, 38(1), 90-94. https://doi.org/10.4103/2319-4170.132885

Chiu, C.-H., Arrigo, L. G., & Tsai, D. (2009). Historical context for the growth of medical professionalism and curriculum reform in Taiwan. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 25(9), 510-514. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70558-3

Chiu, C.-H., Lu, H.-Y., Arrigo, L. G., Wei, C.-J., & Tsai, D. (2010). A professionalism survey of medical students in Taiwan. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Medicine, 2(1), 35-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1878-3317(10)60006-X

Claramita, M., Nugraheni, M. D. F., van Dalen, J., & van der Vleuten, C. (2013). Doctor-patient communication in Southeast Asia: A different culture? Advances in Health Sciences Education, 18(1), 15-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-012-9352-5

Cohen, J. J. (2007). Viewpoint: Linking professionalism to humanism: What it means, why it matters. Academic Medicine, 82(11), 1029-1032. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000285307.17430.74

Doran, G. A. (1983). Scientism vs humanism in medical education. Social Science & Medicine, 17(23), 1831-1835. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(83)90159-4

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129-136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Farooq, Z., Mustaf, T., Akram, A., Khan, M., Amjad, R., Naveed, M., Azhar, A., Chaudhry, A. M., Khan, M. A. Z., & Rafiq, F. (2013). Bedside manners: Do we care? Journal Ayub Medical College Abbottabad, 25(1-2), 179-182.

Ferry-Danini, J. (2018). A new path for humanistic medicine. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 39(1), 57-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-018-9433-4

Fones, C., Heok, K. E., & Gan, G. L. (1998). What makes a good doctor: Defining the ideal end-product of medical education. Academic Medicine, 73(5), 571-572. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199805000-00029

Gold, A. P. (2018). Definition of humanism. Gold Foundation. Retrieved September 21, 2021, from https://www.gold-foundation.org/definition-of-humanism/

Haque, O. S., & Waytz, A. (2012). Dehumanization in Medicine: Causes, solutions, and functions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(2), 176-186. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611429706

Hauck, F. R., Zyzanski, S. J., Alemagno, S. A., & Medalie, J. H. (1990). Patient perceptions of humanism in physicians: Effects on positive health behaviors. Family Medicine, 22(6), 447-452.

Ho, M.-J., Yu, K.-H., Pan, H., Norris, J. L., Liang, Y.-S., Li, J.-N., & Hirsh, D. (2014). A tale of two cities: Understanding the differences in medical professionalism between two Chinese cultural contexts. Academic Medicine, 89(6), 944-950. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000240

Hu, X. (2016). Education as a starting point for preventing medical violence: Implications for medical violence in China. A commentary on Tan MF et al.” Nursing management of aggression in a Singapore emergency department: A qualitative study” Nursing & Health Sciences, 18(4), 539.

Iqbal, S. P. (2010). Family medicine in undergraduate medical curriculum: A cost-effective approach to health care in Pakistan. Journal Ayub Medical College Abbottabad, 22(4), 207-209.

Islam, M. Z., Salam, A., Helali, A. M., Rahman, Z., Wan, W. P. E., Ismail, S., Rahman, N. I. A., & Haque, M. (2014). Comparative study of professionalism of future medical doctors between Malaysia and Bangladesh. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science, 4(4), 66-71.

Jiang, B., & Liu, H. (2014). Constructing the discipline of humanistic medicine on Mainland China. Chinese Education & Society, 47(3), 70-73.

Kaga, K., & Asakage, T. (2007). Medical education by bedside learning – Helping medical students to interact with patients who have head and neck cancer. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 127(4), 408-410. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480601011485

Karunakaran, I., Thirumalaikolundusubramanian, P., & Nalinakumari, S. D. (2017). A preliminary survey of professionalism teaching practices in anatomy education among Indian Medical Colleges. Anattomical Sciences Education, 10(5), 433-443. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1679

Kelly, M., & Dornan, T. (2016). Mapping the landscape or exploring the terrain? Progressing humanism in medical education. Medical Education, 50(3), 273-275. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12967

Kosik, R. O., Huang, L., Cai, Q., Xu, G.-T., Zhao, X., Guo, L., Tang, W., Chen, Q., & Fan, A. P.-C. (2014). The current state of medical education in Chinese Medical Schools: Humanities and medical ethics. Chinese Education & Society, 47(3), 74-87. https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932470308

Lee, Y.-M., & Ahn, D.-S. (2004). Medical-themed film and literature course for premedical students. Medical Teacher, 26(6), 534-539. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590412331282318

Lin, S. C., Hsu, J., & Fan, V. Y. (2009). “Silent virtuous teachers”: Anatomical dissection in Taiwan. BMJ, 339(b5001). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b5001

Liu, S., & Li, Y. (2012). Analysis of the status quo of humanistic quality-oriented education in medical colleges and universities. International Education Studies, 5(1), 216-220. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v5n1p216

Liu, Y., & Cheng, X. (2017). An upcoming program for medical humanities education in Fudan University’s School of Basic Medical Sciences. BioScience Trends, 11(2), 152-153. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2017.01094

Maheux, B., Beaudoin, C., Berkson, L., Côté, L., Des Marchais, J., & Jean, P. (2000). Medical faculty as humanistic physicians and teachers: The perceptions of students at innovative and traditional medical schools. Medical Education, 34(8), 630-634. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00543.x

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L. A., & PRISMA-P Group (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Montgomery, L., Loue, S., & Stange, K. C. (2017). Linking the heart and the head: Humanism and professionalism in medical education and practice. Family Medicine, 49(5), 378-383.

Mostafa, A., Hoque, R., Mostafa, M., Rana, M. M., & Mostafa, F. (2014). Empathy in undergraduate medical students of bangladesh: Psychometric analysis and differences by gender, academic year, and specialty preferences. ISRN Psychiatry, 2014, 375439. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/375439

Moyer, C. A., Arnold, L., Quaintance, J., Braddock, C., Spickard, A., Wilson, D., Rominski, S., & Stern, D. T. (2010). What factors create a humanistic doctor? A nationwide survey of fourth-year medical students. Academic Medicine, 85(11), 1800-1807. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f526af

Nakayama, D. K. (2009). Professionalism in Kurosawa’s medical dramas. Journal of Surgical Education, 66(6), 395-398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.06.001

Notzer, N., Abramovitch, H., Dado-harari, R., Abramovitz, R., & Rudnick, A. (2005). Medical students’ ethical, legal and cross-cultural experiences during their clinical studies. Israel Medical Association Journal, 7(1), 58-61.

Ooi, S. B. S., Tan, C. W. T., & Frambach, J. M. (2021). Who is an effective clinical teacher from the perspectives of medical students and residents? The Asia Pacific Scholar, 6(1), 40-48. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-1/OA2227

Pacifico, J. L., Villanueva, J. A. S., Heeneman, S., & van der Vleuten, C. (2020). How perceptions of residents toward assessment influence learning: A qualitative study. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 5(1), 46-53. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-1/OA2080

Pan, H., Norris, J. L., Liang, Y.-S., Li, J.-N., & Ho, M.-J. (2013). Building a professionalism framework for healthcare providers in China: A nominal group technique study. Medical Teacher, 35(10), e1531-e1536. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.802299

Potash, J., & Chen, J. (2014). Art-mediated peer-to-peer learning of empathy. The Clinical Teacher, 11(5), 327-331. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12157

Qian, Y., Han, Q., Yuan, W., & Fan, C. (2018). Insights into medical humanities education in China and the West. Journal of International Medical Research, 46(9), 3507-3517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060518790415

Rao, K. H., & Rao, R. H. (2007). Perspectives in medical education 5. Implementing a more integrated, interactive and interesting curriculum to improve Japanese medical education. Keio Journal of Medicine, 56(3), 75-84. https://doi.org/10.2302/kjm.56.75

Rider, E. A., Kurtz, S., Slade, D., Longmaid, E., Ho, M.-J., Pun, J. K., Eggins, S., & Branch, W. T. (2014). The international charter for human values in healthcare: An interprofessional global collaboration to enhance values and communication in healthcare. Patient Education and Counseling, 96(3), 273-280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.06.017

Rios, I. C. (2016). The contemporary culture in medical school and its influence on training doctors in ethics and humanistic attitude to the clinical practice. International Journal of Ethics Education, 1(1), 173-182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-016-0012-0

Salam, A., Chew, O. S., Mazlan, N. F., Hassin, H., Lim, S. L., & Abdullah, M. H. (2012). Professionalism of future medical professionals in universiti kebangsaan Malaysia (ukm) medical centre. International Medical Journal, 19(3), 224-228.

Saw, A. (2018). A new approach to body donation for medical education: The silent mentor programme. Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal, 12(2), 68-72. https://doi.org/10.5704/MOJ.1807.015

Schattner, A., Rudin, D., & Jellin, N. (2004). Good physicians from the perspective of their patients. BMC Health Services Research, 4(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-4-26

Schouten, B. C., & Meeuwesen, L. (2006). Cultural differences in medical communication: A review of the literature. Patient Education and Counselling, 64(1-3), 21-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.014

Shrank, W. H., Reed, V. A., & Jernstedt, C. (2004). Fostering professionalism in medical education: A call for improved assessment and meaningful incentives. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(8), 887-892. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30635.x

Singh, M., & Talwar, K. K. (2013). Putting the humanities back into medicine: Some suggestions. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 10(1), 54-55. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2013.013

Song, P., Jin, C., & Tang, W. (2017). New medical education reform in China: Towards healthy China 2030. BioScience Trends, 11(4), 366-369. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2017.01198

Song, P., & Tang, W. (2017). Emphasizing humanities in medical education: Promoting the integration of medical scientific spirit and medical humanistic spirit. Bioscience Trends, 11(2), 128-133. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2017.01092

Tham, K.-Y. (2007). 360 Degrees feedback for emergency physicians in Singapore. Emergency Medicine Journal, 24(8), 574-575. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2007.047530

Thibault, G. E. (2019). Humanism in Medicine: What does it mean and why is it more important than ever? Academic Medicine, 94(8), 1074-1077. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002796

Thomas, A., Lubarsky, S., Durning, S. J., & Young, M. E. (2017). Knowledge syntheses in medical education: Demystifying scoping reviews. Academic Medicine, 92(2), 161-166. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001452

Tokuda, Y., Hinohara, S., & Fukui, T. (2008). Introducing a new medical school system into Japan. Annals of the Academy of Medicine Singapore, 37(9), 800-802.

Tsai, D. F.-C. (2001). How should doctors approach patients? A Confucian reflection on personhood. Journal of Medical Ethics, 27(1), 44-50. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.27.1.44

Tsai, T.-C., Lin, C.-H., Harasym, P. H., & Violato, C. (2007). Students’ perception on medical professionalism: The psychometric perspective. Medical Teacher, 29(2-3), 128-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701310889

United Nations Statistics Division. (n.d.). UNSD — Methodology. United Nations. Retrieved September 23, 2021, from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/

Wald, H. S., Anthony, D., Hutchinson, T. A., Liben, S., Smilovitch, M., & Donato, A. A. (2015). Professional identity formation in medical education for humanistic, resilient physicians: Pedagogic strategies for bridging theory to practice. Academic Medicine, 90(6), 753-760. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000725

Wang, X., Shih, J., Kuo, F.-J., & Ho, M.-J. (2016). A scoping review of medical professionalism research published in the Chinese language. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 300. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0818-7

Wong, Y. F., Lin, S. J., Cheng, H. C., Hsieh, T. H., Hsiue, T. R., Chung, H. S., Tsai, M. Y., & Wang, M. R. (2012). The formation and performance of medical humanities by interns in a clinical setting. Tzu Chi Medical Journal, 24(1), 5-11.

Woratanarat, T. (2014). Higher satisfaction with ethnographic edutainment using YouTube among medical students in Thailand. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 11. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2014.11.13

Yazigi, A., Nasr, M., Sleilaty, G., & Nemr, E. (2006). Clinical teachers as role models: Perceptions of interns and residents in a Lebanese medical school. Medical Education, 40(7), 654-661. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02502.x

Zhang, D., & Cheng, Z. (2000). Medicine is a humane art. The basic principles of professional ethics in Chinese medicine. The Hastings Center Report, 30(4), S8-S12.

Zhu, C., Yap, R., Lim, S., Toh, Y., & Loh, V. (2021a). Coding sheet (Humanism in Medical Education – A Scoping Review) [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14245850.v1

Zhu, C., Yap, R., Lim, S., Toh, Y., & Loh, V. (2021b). Data Abstraction Sheet for Thematic Analysis (Humanism in Medical Education – A Scoping Review) [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14245991.v1

*Cindy Shiqi Zhu

National University Health System,

1E Kent Ridge Road,

Singapore 119228

Email: Shi_Qi_ZHU@nuhs.edu.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.