The crisis “Archetypogram” – of prisoners, soldiers, sages and jesters

Submitted: 30 August 2020

Accepted: 12 November 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 83-86

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/SC2390

Rahman Habeebul

Department of Psychiatry, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Archetypes in psychology are complete models of behaviours, thoughts and feelings, representative of universal experiences. From Plato’s description of Forms to Jung’s analytical introduction to archetypes in psychology, to common use of Moore’s masculine archetypes in popular culture, we use such “complete representations” to enable change.

Methods: In examining psychologically driven responses to the recent and ongoing pandemic crisis, the use of a graphic representation of interacting archetypes is proposed—the ‘archetypogram’.

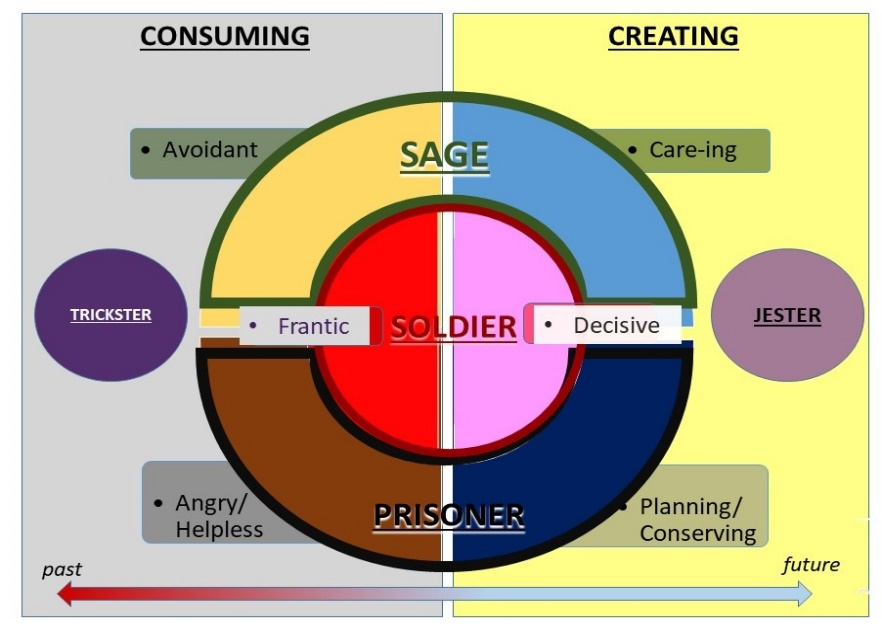

Results: Drawing on concepts from psychodynamic therapy practise, including Transactional Analysis and Jungian theory, four main archetypes are proposed for their interdependence—the prisoner, the soldier, the sage and the jester/trickster, and a model describing their interactions is presented with the intention of enabling helpful behaviours in response to crisis. The model further proposes positive and negative positions within each archetype, labelled as ‘creating’ and ‘consuming’ behaviours respectively. The ‘archetypogram’ thus is a visual representation of three main components – the four archetypes, creating vs consuming behaviours, and movement between the various positions. Use of the ‘archetypogram’ is aimed at enabling individuals in crisis to move from consuming to creating behaviours.

Conclusion: The ‘archetypogram’ is a model of change which may be applied to persons distressed in crisis, and is able to move behaviours towards positive and creating self-states.

Keywords: Archetypes, Psychology, Crisis, Distress

I. INTRODUCTION

This was a crisis borne on the wings of travellers, leaving in its wake the term ‘a new norm’. In reflecting on observed and experienced emotional responses to the crisis, a structure emerged that identified three main themes—1) feelings of helplessness 2) seemingly never-ending activity and 3) a wish to be able to rise above billowing waves of information and misinformation. Hence the archetypes of a prisoner, a soldier and a sage seemed appropriate.

It was expected that psychological reactions of anxiety, worry, grief and helplessness would run their course in this new crisis, but behavioural responses were unpredictable, from hoarding of toilet roll to disregard of rules and breaking of lockdown laws, to apathy. Why was there a difference between a leader of a nation (Luce, 2020) and a 9-year-old girl (Harris, 2020); one denying the problem at its outset, and the other, deciding to sew personal protective equipment (PPE) gowns to help her local doctors? What enables one person to do what needs to be done in crisis, and yet paralyses another into inaction? Many concepts have been put forth, with names such as grit, resilience, and growth mindset, but are there quick descriptors we can apply, that can help us move out of unhelpful states into more effective, useful ways of being?

II. OBSERVATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

We gravitate towards archetypes—“whole” descriptions of images that we identify with externally, and which we identify within ourselves internally. Jung’s description of archetypes has enabled a scaffold on which we can build our understanding of basic human reactions and behaviours in a Gestalt manner. In archetypes we unite both unconscious and conscious domains of being, and place intention second to observation.

The first evident experiences observed in the thick of the outbreak were feelings of being stuck, or being held hostage by the situation with feelings of helplessness that imprison the person. The prisoner was both angry and sad, and endured a mind filled with comparisons e.g. “Were there other prisoners being better treated? Was the suffering equal? Would someone else gain whilst we were denied of something possibly essential to our well-being, such as PPE?” Locus of control was felt externally (Rotter, 1954).

Amongst those who would put action to thought, a different set of behaviours was noted. There was a sense of constant effort, of having to negotiate endless tasks for a small ‘win’. Life was a blur of activity with anticipation of further problems, and resentment (signalling a slip back into prisoner state), but most times the effort of doing kept away negative emotions. This seemed to be the role of a tireless soldier, who would get wounded through unpreparedness.

There was yet a third group, who seemed untouched by the outbreak. They would go about their usual activities, or turn to alternatives effortlessly. This group I called the sage, and hypothesised that few of us would achieve the transcendental nature they exuded, in keeping with Maslow’s topmost hierarchy of being values (Maslow, 1998).

However, referencing Transactional Analysis (Berne, 1961) where the ego-states of Parent, Adult and Child were further divided into negative and positive functional states depending on how stable they were, a further split within the three archetypes could be seen, with negative positions and positive positions. Hence, for the prisoner archetype, whilst inactivity was observed as a behaviour, the prisoner in a positive position was able to plan, or conserve parts of themselves for further action, to either rise as a soldier or guide as a sage.

The positive position of soldier archetype was decisive, enabling energy to effect change without burning themselves out, and able to make difficult decisions. Behaviour was internally motivated and pragmatically guided by agency.

For the sage archetype, the positive position enabled them to nurture those around, lending stability to the system while being transcendental- as encompassed in the description by Maslow who placed this at the apex of the hierarchy of needs. Such a person is ‘care-ing’, not just caring of those around him or her, but also actively engaged in ‘care’ which is a constant state of being present.

III. INTERVENTIONAL PERSPECTIVE

Pathological emotions, thoughts and behaviours were proposed to arise from a primary prisoner state. Subsequently, as responses to helplessness and anger, three main behaviours were noted. 1) Continued inactivity (staying in the helpless prisoner state). 2) Busyness in ‘doing’, but where excessive activity was used to deflect uncomfortable feelings of helplessness (escape into soldiering) or 3) Non-responsiveness, where the uncomfortable feelings are avoided altogether (escape into sageing). These corresponded to efforts to defeat the source of conflict, but being ineffective, resulted in inaction (self-defeat), ineffective activity (other-defeat) or avoidance (reality-defeat).

Figure 1. The Crisis Archetypogram

If we were to look to the negative positions, we see the behaviours as ‘consuming’, where either time, effort or emotional energy are consumed with poor outcomes, or no change in adapting to crisis.

If we were to look to the positive positions, we see the behaviours as ‘creating’ – ideas are born, work is done to engage parts of the system, there is nurturing of others and effort is concise, allowing adaptation and solving of problems.

In looking at ‘creating’ from the positive position, a further archetype emerges—that of the jester. This was the archetype who was flexible and not imprisoned, not always embattled nor always aloof and calm. This archetype would defuse tense situations with humour as a mature defence mechanism. The utility of the jester lies in the ability to bind people (and oneself) to a common cause; in the absence of hugs, laughter does a fair job of oxytocin production, and of fostering attachment. Pulled into negativity however, the jester’s negative position manifests as a trickster who would undermine with cunning the work done by the planning prisoner, the decisive soldier and the nurturing sage. The trickster at work was observed in the form of self-sabotage, or by disrupting efforts of the group with jokes belittling the efforts of others.

A. Completing the Circle – The ‘Archetypogram’

The ‘Archetypogram’ in Figure 1 seeks to visually represent the interconnectedness of the various archetypes, in positive (creating) and negative (consuming) positions. How may we use such a crisis archetypogram to help ourselves and those around us?

The first step would be to identify where we are in the archetypogram—remembering that the position we are holding is temporary and a state (a current and temporary manner of being or interacting in domains of thoughts, feelings and behaviour), not a trait (longer term more durable repeated patterns of interactions).

The second regular step is to move to creating rather than consuming, and meeting the needs of the future instead of being mired in the past. In times of crisis, resources are limited. By moving to a creating state (which is often creative), we make better use of resources available, or contribute more if we agree to change. In a consuming state, time is a price to pay for opportunity lost when not moving forward, even if no other resources are used (anxiety paralysis).

B. Limitations in Change

Having applied the archetypogram in change management, limitations in effectiveness have been observed in situations where either there was a clinical disorder giving rise to anxiety and depression, or if there was resistance to the idea of change being possible within the archetypogram (similar to being in the pre-contemplative state of change). It is hoped that with development of the archetypogram, limited therapy sessions may be used to address clinical disorders.

IV. CONCLUSION

Whilst it is ideal that we move in the general direction of actualization we need to be mindful of limitations in resources; flexibility in approach is paramount, as is being kind to ourselves no matter the approach we adopt.

In a crisis, the ‘work to do’ therefore is to:

1. Identify the state we are in – Prisoner/ Soldier/ Sage/ Jester-Trickster.

2. Identify the outcome of our behaviours – creating or consuming.

3. Identify how we can move ourselves from a consuming to a creating position, first by moving within our archetype (e.g. from angry/ helpless prisoner, to a conserving/ planning prisoner), then up archetypes (eg on to a decisive soldier, and eventually to a nurturing and care-ing sage). The movement can be internal via self-awareness (a practiced skill incorporating conservation of energy by mindfulness/ relaxation exercises and problem solving) or external via a coach, counsellor or therapist.

4. Be aware of the tendency to move upwards within the consuming rank states where avoidance and burnout from the sage and soldier states respectively can reinforce a primary angry / helpless prisoner’s distressed negative position.

5. Be mindful that the distressed position is often at the base of what one feels and thinks as ‘problems’. Emotional responses of grief, anxiety and anger arise from helplessness or loss, and these responses can be true of individuals as well as groups, but still amenable to working through with the aid of the archetypogram.

In conclusion, while the use of archetypes in verbal tradition is established, the visual archetypogram proposes an exciting model to move behaviours in crisis towards positive and creating self-states, in fields ranging from coaching, to counselling, to psychotherapy.

Note on Contributor

Dr Habeebul Rahman is solely responsible for all observations and ideas contained within this manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics review (including informed consent) was not sought for this manuscript owing to the hypothetico-deductive nature of the paper.

Acknowledgement

The writer wishes to acknowledge TTSH Department of Psychiatry, Organisational Development and Operations for their contribution to the development of this work.

Funding

No funding was sought or obtained for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

No conflicts of interest.

References

Berne, E. (1961). Transactional analysis in psychotherapy: A systematic individual and social psychiatry. Grove Press.

Harris, E. (2020, May 11). For Malaysian schoolgirl, homework is sewing PPE gowns to help beat coronavirus. Reuters https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-malaysia-protectiv-idUSKBN22N037

Luce, E. (2020, May 17). Inside Trump’s coronavirus meltdown. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/world/united-states/inside-trumps-coronavirus-meltdown

Maslow, A. H. (1998). Toward a psychology of being. Wiley.

Rotter, J. B. (1954). Social learning and clinical psychology. Prentice-Hall.

*Rahman Habeebul

Tan Tock Seng Hospital,

11 Jalan Tan Tock Seng,

Singapore 308433

Email: habeebul_rahman@ttsh.com.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.