Attitudes of teaching faculty towards clinical teaching of medical students in an emergency department of a teaching institution in Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic

Submitted: 19 July 2020

Accepted: 7 October 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 67-74

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/OA2347

Tess Lin Teo, Jia Hao Lim, Choon Peng Jeremy Wee & Evelyn Wong

Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Singapore experienced the COVID-19 outbreak from January 2020 and Emergency Departments (ED) were at the forefront of healthcare activity during this time. Medical students who were attached to the EDs had their clinical training affected.

Methods: We surveyed teaching faculty in a tertiary teaching hospital in Singapore to assess if they would consider delivering clinical teaching to medical students during the outbreak and conducted a thematic analysis of their responses.

Results: 53.6% felt that medical students should not undergo clinical teaching in the ED and 60.7% did not wish to teach medical students during the outbreak. Three themes arose during the analysis of the data – Cognitive Overload of Clinical Teachers, Prioritisation of Clinical Staff Welfare versus Medical Students, and Risk of Viral Exposure versus Clinical Education.

Conclusion: During a pandemic, a balance needs to be sought between clinical service and education, and faculty attitudes towards teaching in high-risk environments can shift their priorities in favour of providing the former over the latter.

Keywords: Disease Outbreak, Pandemic, Faculty, Medical Students, Attitudes, Clinical Teaching, Emergency Medicine

Practice Highlights

- In a pandemic, a balance needs to be sought between clinical education and risking learner exposure to the virus.

- A crisis situation can affect educators’ priorities and attitudes towards the provision of clinical education, in favour of providing crucial clinical services.

I. INTRODUCTION

Since the first reported cases of COVID-19 infections in Wuhan, in December 2019, the month of January 2020 saw Singapore’s Ministry of Health (MOH) issue guidelines and implement a series of calibrated defensive measures to reduce the risk of imported cases and community transmission (Lin et al., 2020; WHO, 2020). Singapore has a Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) framework, which guides the nation’s response to various emerging infectious diseases outbreaks. The four-level colour-coded system of Green, Yellow, Orange and Red, describes the increasing severity of the outbreak in the community (Quah et al., 2020).

The Department of Emergency Medicine (DEM) of Singapore General Hospital saw 130 000 visits in 2019 (SGH, 2019). It hosted 158 medical students (MS) through the year. Aside from some elective students, the majority were in their second year of clinical postings. Formal clerkships consisted of four weeks of clinical exposure in which they were expected to clerk and present cases to teaching faculty and perform minor procedures such as intravenous cannulation and insertion of bladder catheters etc., with about nine hours of classroom tutorials.

In early January 2020, DORSCON yellow was declared, indicating either a severe outbreak outside Singapore or that the disease was contained locally with no significant community spread (Quah et al., 2020). All DEM staff were required to wear personal protective equipment (PPE). Hospital elective surgeries were postponed. Other outbreak measures included setting up new isolation areas for patients. DEM staff had their leave embargoed to ensure that there was adequate manpower to staff these areas in anticipation of a gradually worsening outbreak (Chua et al., 2020).

On 7 February 2020, the outbreak alert rose to DORSCON Orange (DO) as there were cases of community transmissions (Quah et al., 2020). Based on previous experience managing the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak 17 years prior, the DEM transitioned to an Outbreak Response Roster, where physicians and nurses of the DEM were split into teams that worked 12 hour shifts, with no overlapping shifts, hence limiting staff contact to only those within their teams (Chua et al., 2020). With DO in effect, the department needed to come to a rapid decision about whether or not to accept MS in the ED. A group of 12 MS that the DEM was supposed to host this April already had their clerkship cancelled due to concerns of breaching infection control and safe distancing measures. There have been no studies to date on faculty attitudes towards clinical teaching of MS during a pandemic, although papers have been published about students’ attitudes towards clinical training during disease outbreaks. The Clerkship Director conducted a short and focused survey amongst the faculty between the 27th-29th of March, amidst rising public concerns that the country might soon be locked down, to explore their attitudes on having MS clerkships during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of this survey allowed the Director to quickly understand the sentiments of the faculty and thus decided that an entirely remote, online teaching program would be created instead. 9 days after the survey, on the 7th of April, the Singapore government officially announced the implementation of a lockdown, known locally as a ‘circuit breaker’ (Quah et al., 2020).

II. METHODS

Clinical teachers of the DEM were issued an anonymous survey over a period of three days via an online survey tool, SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com). Participants were informed prior to completing the survey that it was anonymous, and by proceeding with the survey they consented to the results being used for research purposes. The data collected included their professional appointments in the department and two yes/no questions: “Do you think medical students should be performing their EM clerkship during DO?” and “Are you keen on teaching MS clinically during DO?”. Participants answering “No” to the latter were asked to elaborate. All participants were asked to write about any concerns they had about having MS in the emergency department (ED) during DO. No other personal identifying information was sought. The survey was deliberately kept short and easy to answer to promote staff participation within the short timeframe the DEM had to make the decision about accepting students. Informed consent was waived as per the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

A simple descriptive quantitative analysis of responses to the 1st two yes-no questions identified the overarching sentiment of the department towards hosting MS during DO and was followed by a thematic analysis of the free-text answers to the last two open-ended questions (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

As many participants used the last question (‘any other comments?’) to emphasise or elaborate on the preceding question (‘why aren’t you keen to teach?’), the majority of the qualitative data gathered pertains to the issues of having MS in the department during DO. There was a paucity of data detailing why participants were in favour of teaching MS, as the survey did not specifically ask this. Hence, the authors chose to focus on analysing the responses of participants who were not keen to teach during this time. This analysis yielded three different themes. However, a small number of respondents supportive of MS felt strongly about teaching and volunteered their reasons in response to the last question. While this data is insufficient to support a robust thematic analysis, a small section is included at the end in order to present as complete a discussion as possible.

III. RESULTS

A. Participant Background

Participants consisted of Emergency Medicine (EM) specialists, permanent registrars or middle grade staff and EM senior residents. These groups were chosen because they each hold significant roles, such as being named supervisors or clinical instructors of MS, and have considerably more contact time with MS in the DEM as opposed to nursing staff or junior doctors.

B. Quantitative Results

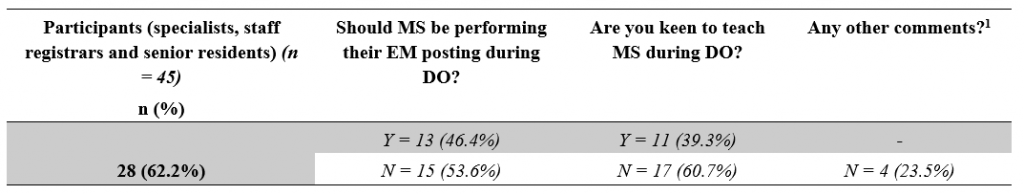

A total of 28 out of 45 (62.3%) responses were recorded. Except for two individuals, all other respondents in favour of hosting MS in the ED during DO (46.4%) were also keen to teach them. About two-thirds of the participants (60.7%) were not keen to teach MS during DO. However, of this latter group, 23.5% of respondents offered (without prompting) a compromise – where they proposed teaching only during the relatively less busy night shifts, in their response to ‘Any other comments?’ Table 1 shows the breakdown of responses.

Table 1: Responses broken down by question.

[1]Number of participants who offered the compromise of teaching during the relatively less busy night shifts despite indicating they were not keen to teach MS.

C. Qualitative Results – Reasons Against

Each of the three themes presented here begins with a short paragraph that describes the situational context in which this survey took place, followed by a series of selected statements, and ends with a general summary and discussion of the responses within the respective theme. In order to maintain the authenticity of the data, each response is reproduced verbatim, sometimes in Singlish, the local colloquial variety of Standard Singaporean English (Bokhorst-Heng, 2005). Any edits to the text for clarification purposes have been clearly identified.

1) First theme: Cognitive overload of clinical teachers– There is only so much one can handle: Emergency physicians are no strangers to high stress environments, and are aware that as frontline workers they will be at the forefront in dealing with any emerging infectious disease. The move into DO represented the shifting of the local virus epidemiology from predominantly imported cases that could be easily identified and isolated, into the community-at-large. With this shift came changes to existing workflows and the re-arrangement of department space to form isolation areas for treating potential infectious cases. The implementation of a strict team-based roster described earlier meant that almost half the entire department would not physically meet the other half, and a surge in manpower requirements saw many junior doctors from other departments being rotated into the ED to help tackle the increased clinical load. Being new to the DEM, these new doctors required more supervision and assistance in adapting to the unfamiliar work environment. Responses that supported this theme include:

“High clinical load, long hours. Already cognitively overloaded. Not conducive for teaching. New [junior doctors] need to be taught also.”

Participant #6, Specialist

“Focus on daily evolving challenge first.” and in response to the last question “Please no.”

Participant #2, Senior Resident

“During DORSCON ORANGE we are in stress, if clinical teaching sessions start then other [doctors’] stress and workload level will increase.”

Participant #25, Staff registrar

“May be more a hassle if we have to look after the new [junior doctors] rotating and students [as well].”

Participant #4, Specialist

“We are also in a 12-hour outbreak roster which is physically, emotionally and mentally draining. Teaching students in this environment is far from ideal” and in response to the last question “Am fairly strongly against this idea”.

Participant #8, Specialist

“Day shifts no bandwidth to teach […] also can’t pay attention to [medical students] during day shifts, too tiring and too busy […] but I feel I can’t do [medical students] justice because I can’t debrief after a shift either, too tired.”

Participant #17, Specialist

Many of these responses conveyed a sense of exhaustion, reflecting the toll that constant workflow changes, longer work hours and relative social isolation was taking on the faculty. Teaching and supervising MS appeared to be viewed as a “hassle” or “extra work”, an additional drain to a clinical faculty’s energy during a busy and stressful shift.

This brought the department to a discussion on the provision of clinical services versus clinical education – whether teaching the next generation of future doctors was as important as treating the patient in front of us. One school of thought held that as clinician educators, physicians should – as the name implies – be clinicians first before educators. However, the interplay between these two roles is likely dependent on the faculty’s attitudes towards learners, as will be described later. Being cognitively overloaded naturally results in a shuffling of One’s priorities, which is seen next.

2) Second theme: Prioritisation of staff welfare – whose welfare is more important, staff or students? : It is well known that mental health can be adversely affected in crisis situations, and as the COVID-19 situation unfolded, boosting morale and maintaining the welfare of all staff became an important consideration (Matsuishi et al., 2012; McAlonan et al., 2007). At the forefront of this effort was the need to provide the staff with a supply of good quality personal protective equipment (PPE) so the staff would feel safe and confident in existing infection control measures. Although Singapore had yet to experience a shortage of PPE, there was still a concerted effort made by all hospitals to conserve these resources. Staff wellness was a theme seen in several responses:

“[I] can’t do the [junior doctors] justice because having a [medical student] attached to them is another stressor in an already stressful shift.”

Participant #17, Specialist

“Having to keep our doctors and nurses safe takes up a lot of energy. Students are young and naïve and will require even more time and resources to ensure they are safe.”

Participant #22, Specialist

“Furthermore, they will need to use PPE and again this should be conserved during the period of the outbreak.”

Participant #27, Specialist

“Medical students are important for future but I feel staff currently working in the department should be look after well.”

Participant #25, Staff registrar

“Waste PPE.”

Participant #20, Specialist

The importance of conserving PPE during a pandemic is undisputed and the concern that MS would use them up is valid. It was interesting to note in these responses hints of an “us-versus-them” mentality, where MS were seen as competition for the limited resources of PPE, time, and energy. Students were not viewed as part of the DEM team and perceived more as “stressors”, who required attention because they were “young and naïve”, and their use of PPE was viewed as a “waste”. This identification of an “in-group” of staff and an “out-group” of students led to a prioritisation or favouring of the former over the latter. This behaviour can be explained by the Social Identity Theory (SIT), which states that part of an individual’s self-image or self-concept is derived from the social groups to which they perceive themselves to belong to (Hogg & Reid, 2006; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Thus, in order to maintain a positive self-image, there is a tendency for people to favour the in-group and discriminate against the out-group. This phenomenon was famously demonstrated by Tajfel et al in their Minimal Group Paradigm studies, which essentially showed that the mere perception of belonging to one of two distinct groups was enough to trigger social discrimination between the groups (Tajfel et al., 1971). Behaviour like this is indicative that a significant number of the department hold the belief that there is a distinct divide between students and staff, rather than seeing MS as belonging to the wider group of the medical fraternity. Creating such a divide between staff and student is problematic because it hinders effective teaching, especially because MS will eventually transition from the “out-group” of students to the “in-group” of staff upon graduation, and clinician educators are responsible for providing a safe environment for them to learn in. However, beyond this discussion of intergroup competition, there were concerns amongst the faculty with regards to the appropriateness of siting clinical learning in the high-risk, front-line location of the ED in a pandemic, as discussed in the next theme.

3) Third Theme: Risk of viral exposure vs clinical education – What is the price to pay and who pays it?: During the initial period of DO, medical schools pulled MS out of the clinical environment and moved to online learning, with the aim of protecting them from unnecessary exposure to the virus and for safe distancing. However, when they proposed that students be allowed back into the hospitals after undergoing PPE training, this risk of exposure had not changed, as the number of positive cases was rising daily still. Responses that reflected this theme included:

“Don’t think it’s appropriate to have students around in a high-risk environment.”

Participant #4, Specialist

“Having medical students around not only will expose them to infection it will also compromise the rest of the staff in the event of a breach in infection [protocols]. Also, them just hanging around & not allowed to have hands-on [participation] in the procedures, clerking, [patient] contact etc will not be of any benefit [to them] at this time.”

Participant #7, Senior Resident

“Student safety issue. No minder to ensure students’ adherence to strict PPE as Doctors and Nurses will be busy with clinical service.”

Participant #11, Specialist

“I think medical students are not providing clinical care to patients and having them in the ED increases risk to patients (without the attendant benefits) and increases risk to themselves (without the moral obligation to do so as doctors) and their family.”

Participant #27, Specialist

“Can students be [held] responsible for their own health? Or the school or the department? As doctors, we know it as our duty and occupational hazard. But as students – their duty is to learn (best done in a safe environment), not put their health at risk.”

Participant #6, Specialist

Responses that addressed the risk of virus exposure in the ED could be divided into two groups –those that were predominantly concerned about the students themselves catching the virus, and those that were more concerned about the consequences of such an event. The risk of catching the virus was seen as too high a cost – one that was borne not only by the individual student but by the patients and the staff as well. The benefits of clinical bedside instruction were called into question, as students’ movements would be restricted to low or medium-risk areas only. More than one participant raised the potential issue of students breaching infection control protocol or needing supervision in donning their PPE, despite reassurances given that schools would send MS for PPE training. This reflected a lack of trust in MS – themselves adult learners – who could be reasonably expected to understand the importance of infection control protocols. It begs the question of how big a role the educator plays in the personal safety of a MS and that of the patients and staff they interact with.

D. Qualitative Results – Reasons For

The survey design did not specifically ask responders about their reasons for supporting teaching MS during this pandemic. However, some participants felt strongly enough about this to advocate for clinical postings. Their reasons are shared below.

1) Theme: For the sake of tomorrow – In defence of teaching amidst a crisis:

“I feel we can still provide a meaningful learning experience for these students. We just need to lay out clear instructions and precautions for them to follow. It is a good opportunity to show to students how emergency medicine is adaptive, versatile, and for them to appreciate how quickly workflows can change, or how triage works in a disaster setting.”

Participant # 15, Specialist

“The way it is done has to be different […] the traditional method of teaching, where the students look to the seniors and may expect some form of spoon feeding […] Only when this mind-set is removed, will the tutors […] look at them as part of the team and incorporate them […], and will students see […] themselves as Drs to be [sic], practice safe habits from the very start and protect themselves as the patient’s doctor. This sense of ownership, accountability, professionalism can be started from that stage as a medical student. This is the perfect opportunity to state that this is what is expected and groom them likewise.”

Participant #19, Specialist

“I feel that the teaching should as much as possible be a simulation of working life and that working in high-risk areas such as these gives a semblance of pressure which cultivates good habits such as mindfulness of hand hygiene, donning of PPE etc.”

Participant #26, Senior Resident

The responses share a commonality of seeing the pandemic as an opportunity for modelling positive attitudes that would benefit the student in the future. This point of view advocates for the acknowledgement of the realities of being a doctor and assumes that students are already part of the “in-group” of the medical team rather than the “out-group” as seen in the earlier discussion.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Limitations

This study has its limitations, chiefly being the lack of qualitative data representing the opinions of those who were keen to teach MS as the initial survey was conducted with the purpose of gauging whether or not the department would be open to receiving MS during DO. This lack of data meant that this study is at best a one-sided representation of the department’s opinion.

Additionally, all four of the authors have a keen interest in the education of MS and two of the authors are actively involved in faculty development. They were all both participants in the study as well as its evaluators. Prior to evaluation of results, the authors themselves suspected that majority of the faculty would be too overwhelmed with the changes the pandemic wrought to want to teach students, which may have contributed to confirmation bias in the analysis of the data. However, throughout the analysis, every attempt was made to ensure that the themes uncovered remained true to the data, and much of the original data was reproduced here faithfully to maintain transparency, such that the reader may draw their own conclusions.

Another limitation of the study was that the survey was unable to measure shifts in the attitudes of faculty as the pandemic evolved, which would have allowed us to understand the amplitude of the effect of the pandemic itself more clearly.

B. New Insights

It was worth noting that nearly two-thirds of the department did not want to teach MS during DO, despite each participant having taught MS routinely prior to this pandemic. Initial analysis of the reasons given for this refusal revealed three distinct themes of Cognitive Overload of Teachers, the need to Prioritise Staff Welfare and the Risk of Viral Exposure to Students – themes that are transferrable to many departments involved in pandemic response, regardless of locality.

Expounding further on this topic, it can be seen in some of the responses detailed under the themes of Cognitive Overload and Prioritising Staff Welfare, that there was a perceived increase in the need to supervise the new junior doctors rotating into the department on short notice (as opposed to the junior doctors who were already in the middle of their rotation and thus more familiar with the department’s protocols). This supervision is an important component of the continuing clinical education of junior doctors, which in itself is part of a larger debate surrounding the competing aims of clinical service versus clinical education that has been ongoing for many years (Woods, 1980). It is often the case in EM that when overwhelmed with patients, clinical education is sacrificed for clinical service without much short-term complications. Indeed, even amongst EM residents, more research is needed to define the optimal balance between service and education (Quinn & Brunett, 2009). However, a pandemic presents a rather unique situation in that most junior doctors will not have worked in a pandemic before. Thus, the need to educate junior doctors on both pandemic response and the importance of personal safety – with its direct impact on patient safety – now cannot be sacrificed without directly affecting the provision of clinical service.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to comment on whether educating MS on pandemics through clinical immersion programs during a pandemic better prepares them for future outbreaks, or in the broader sense, whether the clinical education of today’s MS by immersive learning can bolster the clinical service of tomorrow’s junior doctors. In fact, it seems almost premature to consider this question given the paternalistic attitude many of our faculty appeared to have towards students, perceiving them as learners to be looked after – to the extent that they could not even be trusted with their own safety and that of the patients and staff they interact with. Interestingly, this view seems to be shared by MS themselves – an electronic survey conducted at one of Singapore’s medical schools showed that a third of currently enrolled MS were concerned that they might introduce possible risks to the patient should they return to the clinical setting (Compton et al., 2020). These findings are indicative of a more deeply rooted mindset in which the social hierarchy draws a clear line between Teacher and Student. This becomes clearer when one considers that in Confucian Heritage Cultures such as Singapore (Biggs, 1998), the teacher holds great authority and students brought up in such cultures tend to defer to such authority as a matter of course (Ho, 2020). Given the multiple factors that contribute to this debate, it is unlikely that we will be able to arrive at a clear answer without further research, but what is certain is that medical students are not essential workers and, in a pandemic, medical schools need to balance their educational needs and ethical obligations to keep students safe (Menon et al., 2020).

Within our paper, it is heartening that many participants who were not keen to teach still tried to offer a compromise of teaching during the relatively less busy night shifts instead, and that 46% of our department were willing to accept MS during this period. COVID-19 allowed us to uncover some of the underlying attitudes towards MS and to consider them in the context of Singapore’s cultural heritage. These attitudes are important for us to address if we are to improve the delivery of medical education in the ED and we would like to invite the reader to consider whether the same uncovering has occurred in their respective departments.

V. CONCLUSION

The balance between clinical service and clinical education is a precarious one that appears to shift quickly in favour of the former in the high-risk environment of an evolving pandemic, which presents significant challenges even for experienced educators to overcome. As seen in our paper, cognitive overload of educators and the need to prioritise the welfare of junior staff inexperienced in pandemic response takes clear precedence over the education of MS. The paternalistic view that majority of our faculty hold leads to doubts about the ability of MS to keep themselves and their patients safe from virus exposure, doubts that are surprisingly shared by MS as well, and is indicative of the social hierarchy deeply ingrained in Confucian Heritage Cultures such as Singapore and surrounding countries in the region, where students tend to defer to authority as a matter of course. In order to improve as medical educators, we must place further effort into uncovering the underlying attitudes of both faculty and MS and address them in ways specific to our cultural heritage.

Notes on Contributors

Author Teo TL analysed the transcripts, conducted the primary thematic analysis and wrote the manuscript. Author Lim JH co-wrote the manuscript. Author Wee JCP conducted the literature review and developed the manuscript. Author Wong E designed and conducted the study, performed the data collection and developed the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

IRB approval for this study was obtained (SingHealth CRIB reference number 2020/2134).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge all participants of the survey.

Funding

No funding sources are associated with this study.

Declaration of Interest

All authors work in SGH DEM and answered the survey as participants.

References

Biggs, J. (1998). Learning from the confucian heritage: So size doesn’t matter? International Journal of Educational Research, 29(8), 723–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(98)00060-3

Bokhorst-Heng, W. D. (2005). Debating singlish. Multilingua, 24(3), 185–209. https://doi.org/10.1515/mult.2005.24.3.185

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chua, W. L. T., Quah, L. J. J., Shen, Y., Zakaria, D., Wan, P. W., Tan, K., & Wong, E. (2020). Emergency department ‘outbreak rostering’ to meet challenges of COVID-19. Emergency Medicine Journal, 37(7), 407–410. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2020-209614

Compton, S., Sarraf-Yazdi, S., Rustandy, F., & Radha Krishna, L. K. (2020). Medical students’ preference for returning to the clinical setting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medical Education, 54(10), 943–950. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14268

Ho, S. (2020). Culture and learning: Confucian heritage learners, social-oriented achievement, and innovative pedagogies. In C. Sanger & N. Gleason (Eds.), Diversity and inclusion in global higher education (pp. 117–159). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1628-3

Hogg, M. A., & Reid, S. A. (2006). Social identity, self-categorization, and the communication of group norms. Communication Theory, 16(1), 7–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00003.x

Lin, R. J., Lee, T. H., & Lye, D. C. B. (2020). From SARS to COVID-19: The Singapore journey. The Medical Journal of Australia, 212(11), 497-502.e1. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50623

Matsuishi, K., Kawazoe, A., Imai, H., Ito, A., Mouri, K., Kitamura, N., Miyake, K., Mino, K., Isobe, M., Takamiya, S., Hitokoto, H., & Mita, T. (2012). Psychological impact of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 on general hospital workers in Kobe. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 66(4), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02336.x

McAlonan, G. M., Lee, A. M., Cheung, V., Cheung, C., Tsang, K. W. T., Sham, P. C., Chua, S. E., & Wong, J. G. W. S. (2007). Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 52(4), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370705200406

Menon, A., Klein, E. J., Kollars, K., & Kleinhenz, A. L. W. (2020). Medical students are not essential workers: Examining institutional responsibility during the COVID-19 pandemic. Academic Medicine, 95(8), 1149–1151. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003478

Quah, L. J. J., Tan, B. K. K., Fua, T. P., Wee, C. P. J., Lim, C. S., Nadarajan, G., Zakaria, N. D., Chan, S. J., Wan, P. W., Teo, L. T., Chua, Y. Y., Wong, E., & Venkataraman, A. (2020). Reorganising the emergency department to manage the COVID-19 outbreak. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00294-w

Quinn, A., & Brunett, P. (2009). Service versus education: Finding the right balance: A consensus statement from the council of emergency medicine residency directors 2009 academic assembly “Question 19” working group. Academic Emergency Medicine, 16(SUPPL. 2), 15–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00599.x

SGH. (2019). Hospital Overview – Singapore General Hospital. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://www.sgh.com.sg/about-us/corporate-profile/Pages/hospital-overview.aspx

COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) Act 2020. (2020). https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/COVID19TMA2020

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2), 149–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

WHO. (2020). IHR emergency committee for pneumonia due to the novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV transcript of a pressing briefing. Retrived January 30, 2020, from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/transcripts/ihr-emergency-committee-for-pneumonia-due-to-the-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-press-briefing-transcript-30012020.pdf?sfvrsn=c9463ac1_2

Woods, D. (1980). Service and education in residency programs. A question of balance. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 123(1), 44.

*Evelyn Wong

Department of Emergency Medicine,

Singapore General Hospital

Outram Road

Singapore 169608

Email: evelyn.wong@singhealth.com.sg