Patterns of reflective thinking and its association with clinical teaching: A pilot study

Published online: 4 September, TAPS 2018, 3(3), 31-34

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-3/SC1056

Christie Anna1 & Lian Dee Ler2

1National Healthcare Group Polyclinics (NHGP), Singapore; 2Health Outcomes and Medical Education Research (HOMER), National Healthcare Group, Singapore

Abstract

Aims: The evidence on how reflection associates with clinical teaching is lacking. This study explored the reflection pattern of nursing clinical instructor trainees on their clinical teaching and its association with their teaching performance.

Methods: Reflection entries on two teaching sessions and respective teaching assessment data of a cohort of Registered Nurses participating in the National Healthcare Group College Clinical Instructor program (n=28) were retrieved for this study. Reflection entries were subjected to thematic analysis. Each reflection statement was coded and scored according to topics in relevance to three clinical teaching phases – preparation, performance and evaluation. Teaching assessment scores were then used to group the participants into different performance group. Reflection patterns derived from the coding scores were compared across these groups.

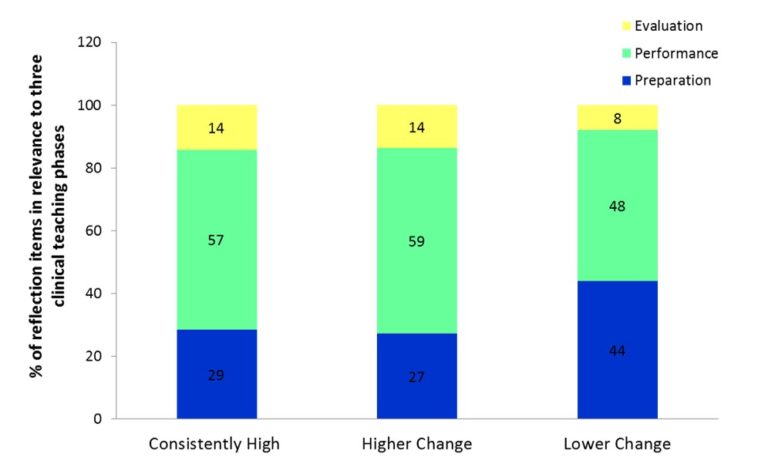

Results: Participants’ reflections focused on the performance phase (57% of reflected items), followed by preparation (30%) and evaluation (13%) phases. To assess the reflection pattern of trainees with differing teaching performance, participants whose teaching assessment scores were already high from first teaching session were classified into Consistently High group (score>22). Remaining participants were further categorized based on their improvement in teaching assessment scores into Higher Change (score difference>1) and Lower Change (score difference≤1). Compared to Lower Change group, participants in the Consistently High and Higher Change groups had higher trend of reflection focus on performance (57% and 59% vs 48%) and evaluation phases (14% and 14% vs 8%), but lower on preparation phase (29% and 27% vs 44%).

Conclusions: The finding suggests a possible role of reflection in teaching performance of nurse clinical instructors, warranting further investigation.

Keywords: Registered Nurses, Clinical Instructor, Reflective Thinking, Clinical Teaching, Reflective Journal

I. INTRODUCTION

The concept of reflection was first articulated by Dewey (Dewey, 1933) and it can be defined as ‘careful consideration and examination of issues of concern related to an experience’ (Kuiper & Pesut, 2004). Since its introduction, reflection has gained a lot of attraction in multiple disciplines and professions, including medicine and nursing. David Kolb, who developed the idea of ‘reflective learning’, is one of the most influential authors who proposed the incorporation of reflection as an educational approach (Kolb, 2015). Kolb suggested that learning should be a dialectic and cyclical process, and in his experiential learning model, suggested that experience is the basis of learning, which cannot take place without reflection. Meanwhile, reflection must be connected to action. In line to this conception, Donald Schön emphasized the importance of the ‘reflective practitioner’, describing reflective practice as the practice by which professionals can become aware of their implicit knowledge base and learn from their action or experience (Schön, 1983).

In the clinical setting, the focus of clinical teaching and learning has shifted from doing, to knowing and understanding (Won & Wong, 1987). In order to understand, one must process information or knowledge in a structured manner and reflect or link new experiences and knowledge with past experiences. This allows the learner to be a ‘reflective practitioner’ and learning to be meaningful. In addition, developing learners’ reflective skills enhances coherence between theoretical and practical components of education programmes (Hatlevik, 2012). Using reflection as a means to bridge the gap between theory and practice, and develop and articulate tacit knowledge is a widely used method in nursing literature (Johns & Joiner, 2002). As reflection is increasingly recognized as a crucial component in nursing education and practice (Nguyen, Fernandez, Karsenti, & Charlin, 2014), it was a timely initiative of the National Healthcare Group College (NHGC) to conduct a Clinical Instructor (CI) programme which factored reflection as an important aspect of the curriculum while assessing the association of reflection to nurses’ teaching performance.

The NHGC conducted a CI programme for the training and development of nursing clinical instructors. The development of reflective skills was incorporated as a methodology in the curriculum. The CI programme consisted of a total of sixteen days, of which six days were spent in the classroom, followed by ten days in the clinical setting as clinical practicum. In addition to the ten days clinical practicum period, participants were granted a one-month period, beginning from the last day of the programme to complete all assessment requirements of the programme. Participants of the programme were Registered Nurses (RNs) with a minimum of three years working experience in the clinical setting and a keen interest in the clinical teaching role. The aim of this study was to explore the reflective thinking of these nurse clinical instructors and its association with their clinical teaching performance during placement of the clinical practicum.

II. METHODOLOGY

Twenty-eight RNs were enrolled in the CI program and participated in this study which used quantitative thematic analysis to establish the relationship of reflective thinking and clinical teaching. During the one-month clinical practicum period of the programme, the CI trainees were required to carry out two clinical teaching sessions and log these cases into their Clinical Practicum Logbooks (CPL).

Clinical practicums took place in the same clinical setting where the RNs worked in. Following each clinical teaching session, they were to reflect upon their teaching and document their reflections in the Reflective Journal (RJ). The RJ contained a set of prompt questions to facilitate reflections: 1) what they had learnt from their clinical teaching; 2) what new learnings from classroom sessions they applied to the clinical setting; and 3) any concerns or doubts arose from their clinical teaching experiences. The CPL and RJ were in partial assessment requirements to successfully complete the CI programme.

At the end of the one-month clinical attachment period, both these documents were retrieved from the database for this study. The RJ was first subjected to thematic coding and analysis. The themes were coded deductively according to three clinical teaching phases – preparation, performance and evaluation. Two researchers who were initially blinded to participants’ teaching performances analysed the reflective journal. Each one independently read and coded each statement of the reflection from the first teaching log according to topics in relevance to the three clinical teaching phases. The two researchers’ respective coding results were then compared to ensure inter-coder reliability. Differences in interpretation were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. To quantify the reflection themes, each reflective statement was coded as one reflected item. The frequency of reflected item for each clinical teaching phase was thus derived. For example, if a participant reflected on the preparation teaching phase, this reflected item was counted towards the reflection frequency for the preparation phase theme.

We also extracted the teaching assessment scores for both teaching sessions from participants’ CPL. Performance scores were then used to group participants according to their teaching performances; how groups were categorised is explained in detail in the results section. In order to analyse patterns of reflective thinking across these groups, the frequency of reflected item for each clinical teaching phase was converted to percentage over the total reflected items.

III. RESULTS

As suggested by Kolb, reflection is critical to connect experience to learning (Kolb, 2015). We thus analysed participants’ RJ on their first clinical teaching experience and explored their learning for clinical teaching through the change in their clinical teaching assessment scores between the first and second teaching sessions. Generally, participants’ reflections focused more on the performance (mean no. of reflected items = 3.8, 57%) as compared to preparation and evaluation (mean no. of reflected items are 2.0 and 0.9, or 30% and 13%, respectively) phases of clinical teaching (Figure 1). The teaching assessment scores of all participants either remained the same or improved across the two clinical teaching. The participants were classified into two groups according to their teaching assessment score in the first teaching. Fourteen participants whose teaching assessment scores were already high from the first teaching log were in the Consistently High group (score > 22). The remaining participants (score ≤ 22) were further classified based on the difference of teaching assessment scores between first and second teaching into Higher Change (difference > 1) and Lower Change (difference ≤ 1) for those with higher or lower improvements in clinical teaching, respectively. Participants in the Consistently High and Higher Change groups had higher trend of reflection focus on performance (57% and 59% vs 48%) and evaluation phases (14% and 14% vs 8%), but lower trend of reflection focus on preparation phase (29% and 27% vs 44%) when comparing to the Lower Change group.

Figure 1. Percentage breakdown of participants’ reflections focus according to their group category

IV. DISCUSSION

The use of clinical logs and reflective journals in the programme was to allow learners to define their experiences in their own words through reflective writing following a practical experience, and thus to validate their own unique experiences. Kobert (1995) illustrated that clinical logs and reflection allowed the learner to see his/her world within a larger context. In addition, learning shifts from a passive to an active process (Callister, 1993). Reflecting on their practice, the clinical logs and reflective journals provided the learners with tools for developing and improving their metacognitive awareness. The ability to develop and subsequently improve reflective thinking skills begins with the awareness of one’s own thinking patterns (i.e. their metacognition) (Fonteyn & Cahill, 1998).

This pilot study set out to describe patterns of reflective thinking among RNs following experiencing clinical teaching sessions. Results from this study provide preliminary support of the relationship between the reflection on different clinical teaching phases and clinical teaching performance of CI trainees. While all participants’ reflection focused mostly on performance phase, those who attained consistent and improved teaching performance showed a higher trend of reflection focus in the performance and evaluation phases but a lower trend of reflection focus in the preparation phase when compared with other participants. In line with this research effort devoted to identify effective reflective practice education (Asselin & Fain, 2013), the understanding of how reflection associates with clinical teaching can inform curriculum design on how nurse educators can teach or scaffold reflection to enhance clinical instructors’ clinical teaching skills.

The assessment structure of the CPL could be a contributing factor in participants’ reflection focus of the teaching phases. The overall weightage of the CPL teaching assessment was 30% of the CI programme. Other assessment requirements for CI programme included developing a lesson plan based on a microteaching conducting session, class participation and presentations during classroom sessions, and doing an online quiz before commencement of the programme. The RJ entries carried a total weightage of 20%, which meant each reflective entry carried a hefty 10%. The CPL teaching performance of the trainees was assessed by their total performance scores in each of the three teaching phases, with the performance phase carrying the highest scores. The preparation and evaluation phases each carried 5 marks, while the performance phase carried 15 marks. The weightage distribution given to each clinical teaching phase could also have been a factor which contributed to participants’ reflection focus – where they tended to focus on the performance phase as it carried the highest weightage of scores among the three teaching phases.

It should be noted, that study limitations included the use of a small sample, all recruited from a single cohort of the CI programme. All participants of this cohort of the CI program were included in this study, with no exclusion criteria or eliminating factors. The RNs were of varying nationalities, with differing years of working experience, holding various educational qualifications, and even differing in age and gender. These factors were not considered in this study on their impact or influence towards their clinical teaching ability, depth of reflection potential or the capacity to translate reflective thoughts into writing. Future research, taking these factors into account, will be critical to further establish the relationship of reflective thinking and clinical teaching.

V. CONCLUSION

Different patterns of reflection were associated with clinical teaching in nurse clinical instructors. Those with consistently good teaching performance, when comparing to those with low or no improvement in teaching, have higher trend of reflection focus in the performance and evaluation phases but lower in preparation phase of their teaching. Similar reflection pattern was also observed in those showing high improvement in teaching. The finding thus suggested a possible role of reflection in clinical teaching performance of nurse clinical instructors which warrants further investigation.

Notes on Contributors

Christie Anna is a nurse educator at the National Healthcare Group Polyclinics, Singapore. She is involved in the development of nursing education.

Lian Dee Ler is a research analyst at NHG-HOMER, the research unit within Education Office of National Healthcare Group, Singapore. She is involved in health profession education research.

Ethical Approval

This study does not require ethics approval as determined by the NHG Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB), Reference 2017/00156.

Declaration of Interest

C. A. is an employee of National Healthcare Group Polyclinics and L.D.L. an employee of National Healthcare Group Singapore. The authors have no financial, consultant and other relationships that might lead to competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This pilot research project was supported by the following colleagues who provided their expertise that greatly assisted the research:

Lim Yong Hao, Research Analyst, NHG-HOMER, Group Education & Research;

Eileen So, Executive, NHG College;

Dong Lijuan, Assistant Director of Nursing, Nursing Services, NHG Polyclinics; and

Poh Chee Lien, Assistant Director of Nursing, NHG HQ, Group Education & Research.

Funding

The authors have no financial relationships.

References

Asselin, M. E., & Fain, J. A. (2013). Effect of reflective practice education on self-reflection, insight, and reflective thinking among experienced nurses: a pilot study. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 29(3), 111–119.

https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0b013e318291c0cc.

Callister, L. C. (1993). The use of student journals in nursing education: Making meaning out of clinical experience. Journal of Nursing Education, 32(4), 185–186.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: a restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Lexington (Massachusetts): D. C. Heath.

Fonteyn, M. E., & Cahill, M. (1998). The use of clinical logs to improve nursing students’ metacognition: A pilot study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(1), 149–154.

Hatlevik, I. K. R. (2012). The theory‐practice relationship: reflective skills and theoretical knowledge as key factors in bridging the gap between theory and practice in initial nursing education. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(4), 868–877.

Johns, C., & Joiner, A. (2002). Guided reflection: Advancing practice. Osney Mead, Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Kobert, L. J. (1995). In our own voice: Journaling as a teaching/learning technique for nurses. Journal of Nursing Education, 34(3), 140–142.

Kolb, D. A. (2015). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education.

Kuiper, R. A., & Pesut, D. J. (2004). Promoting cognitive and metacognitive reflective reasoning skills in nursing practice: Self-regulated learning theory. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 45(4), 381–391.

Nguyen, Q. D., Fernandez, N., Karsenti, T., & Charlin, B. (2014). What is reflection? A conceptual analysis of major definitions and a proposal of a five-component model. Medical Education, 48(12), 1176–1189.

https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12583.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic books.

Won, J., & Wong, S. (1987). Towards effective clinical teaching in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 12(4), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1987.tb01360.x.

*Christie Ann

Email: christie_anna@nhgp.com.sg

*Lian Dee Ler

Email: lian_dee_ler@nhg.com.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.