Characterisations of Māori in health professional education programmes

Published online: 3 September, TAPS 2019, 4(3), 91-98

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2019-4-3/OA2091

Caitlin Harrison1, Rhys Jones2 & Marcus A. Henning3

1The University of Auckland, Aotearoa, New Zealand; 2Te Kupenga Hauora Māori, The University of Auckland, Aotearoa, New Zealand; 3Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, The University of Auckland, Aotearoa, New Zealand

Abstract

Formal Indigenous health curricula often exist in institutional contexts that tacitly condone racist discourses that are at odds with the goal of developing culturally safe health professionals. Recognition of the impact of informal and hidden curricula on learners has increased, yet few studies have provided empirical evidence about this aspect of health professional education. This study sought to examine characterisations of Māori (Indigenous New Zealanders) in learning environments at the University of Auckland’s Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences. A cross-sectional study design based on the Stereotype Content Model elicited student perceptions (n = 444) of stereotype content in undergraduate nursing, pharmacy and medical programmes. The Stereotype Content Model identifies interpersonal and intergroup perceptions in relation to warmth and competence. These perceptions are considered fundamental and universal to the impressions people form when meeting one another. Stereotyping is associated with distinct affective and behavioural responses that can lead to discrimination. In this study, students rated perceived warmth and competence characterisations pertaining to four target ethnic groups (Māori, Pacific Nations, Asian and Pākehā/European). Characterisations of Māori warmth were rated lower than Pacific Nations peoples, comparable to Pākehā/European and higher than characterisations of Asian peoples. In reference to competence characterisations, Māori were rated equal to Pacific Nations peoples and lower than both Asian and Pākehā/European peoples. This study’s results highlight a degree of incongruence between the University of Auckland’s formal Māori Health curricula and messages conveyed in the broader institutional context, with implications for educational outcomes and students’ future clinical practice.

Keywords: Indigenous Health, Health Professional Education, Stereotype Content Model, Informal/Hidden Curriculum

Practice Highlights

- Undergraduate nursing, pharmacy and medical students’ perceptions of ethnic group stereotype content in the University of Auckland’s Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences’ learning environments were evaluated to identify areas of incongruence with the formal Hauora Māori (Māori Health) curriculum.

- The findings indicated that characterisations of Māori are incongruent with formal curricular objectives.

- Māori students perceived characterisations of Māori in their learning environments more negatively than non-Māori students.

- The findings have implications for students’ educational outcomes, their future clinical practice, and Māori workforce recruitment and retention.

I. INTRODUCTION

Indigenous health educators work to enact decolonised, anti-racist curriculum and pedagogies (Curtis, Reid, & Jones, 2014; Jones et al., 2019). The need for transformative teaching and learning in this area is evidenced by persistent ethnic inequities in health outcomes and health care quality (Jones et al., 2010; Wilson & Barton, 2012). In Aotearoa, New Zealand, the context for this study, inequities between Māori (the Indigenous peoples of Aotearoa) and non-Māori are apparent across most health measures, including life expectancy, mortality rates, disease-specific morbidity and many of the key health risk factors and determinants of health (Harris et al., 2012; Ministry of Health, 2015; Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa, 2015). Access to and quality of healthcare is inequitable for Māori compared to non-Māori (Hill, Sarfati, Robson, & Blakely, 2013; Jansen & Jansen, 2013), and in the healthcare system, Māori experience racial discrimination by health professionals (Harris et al., 2012).

Formal Indigenous health curricula exist in concert with and in the context of what Hafferty (1998) identified as the ‘informal’ and ‘hidden’ curriculum. Hafferty (1998) described the ‘informal’ and ‘hidden’ curriculum as the implicit learning and teaching that take place within educational institutions and function at the interpersonal and structural levels, respectively. The resulting tacit knowledge, accrued from multiple experiences, is unexamined, taken-for-granted and tends to reproduce the unjust social orders that formal Indigenous health curricula seek to subvert (Paul, Ewen, & Jones, 2014). Hauora Māori (Māori health) academics at the University of Auckland describe the broader institutional culture and context in which they work as one that often conflicts with the formal Māori health curriculum (Jones et al., 2010). Undergraduate medical students at the University of Auckland have demonstrated both explicit and implicit bias in favour of Pākehā/NZ European New Zealanders (Harris et al., 2018), and Māori students in health professional and health science programs report experiences of racism (Curtis et al., 2012).

The main purpose of this study was to identify areas of incongruence between the University of Auckland’s Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences’ (FMHS) undergraduate medical, nursing, and pharmacy degree programme learning environments (i.e. a ‘hidden/informal,’ institutional curriculum) and the formal Hauora Māori curriculum. Although it has been reported that attitudes among students in health professional training programmes are sensitive to the values of their educational contexts (Howe, 2002), comparable group-level studies have not been conducted in other educational institutions.

This study employs the Stereotype Content Model (SCM) as an analytical tool to investigate student perceptions of ethnic group stereotype content pertaining to Māori in the University of Auckland’s health professional education programmes. The SCM synthesised research on interpersonal and intergroup perception processes with patterns of stereotype content, revealing that warmth and competence perceptions are fundamental and universal to the impressions people form when met with an “other” (Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002). “Others” who are perceived as having positive intentions toward the perceiver are evaluated as high in warmth. Perceived capability(ies) of an “other” to carry out her/his intentions correlate to perceptions of competence. According to Fiske et al. (2002), warmth and competence’s fundamental positioning is a result of humans’ innate concerns regarding status and competition. If the “other” is perceived as a competitive threat to one’s social status, they will be evaluated as low in warmth but highly competent. People(s) perceived as non-threatening are typically characterised as high in warmth, but low in competence. When applied to populations clear patterns emerge, hence the SCM theorises that socio-structural conditions shape intergroup relations, giving rise to patterns of warmth and competence perceptions (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2008). All social groups’ stereotype content profiles can be linked to their relative social positioning and the degree to which they are perceived as competing with the dominant group (Pākehā/NZ Europeans in the context of this study; Cuddy et al., 2008).

Stereotype content was identified as a salient construct for enquiry due to racial stereotypes’ role in creating and maintaining ethnic and racial disparities in health care (van Ryn et al., 2011). In healthcare settings, stereotypes impact the perceptions and behaviours of both patients and clinicians. Stereotype activation, an automatic process in which awareness of relevant stereotypes is triggered during an interpersonal interaction, has been identified as a principal component of provider-mediated unconscious bias (Williams & Mohammed, 2013).

When people receive interpersonal or environmental signals, both explicit and implicit, that aspects of their perceivable identity (e.g. skin colour) could trigger negative judgments or mistreatment, the resulting psychological state is defined as ‘stereotype threat’ (Aronson, Burgess, Phelan, & Juarez, 2013). In healthcare interactions, stereotype threat influences clinician and patient behaviour. Clinician behaviours may trigger stereotype threat, which is likely to impact patient behaviours, which then influences clinicians’ subsequent behaviours (Aronson et al., 2013). The endorsement of negative stereotypes is understood to result in discrimination (Dovidio & Fiske, 2012).

A range of common stereotypes about Māori exist in broader New Zealand society (Sibley et al., 2011), and among health care professionals (McCreanor & Nairn, 2002). For example, Penney, Barnes, and McCreanor (2011) revealed a commonplace practice of stereotyping Māori patients as ‘non-compliant,’ a label with significant implications for the patient-provider relationship. Health professional education and training programmes can reinforce stereotypes and influence racial and ethnic bias among learners (Jones et al., 2019; van Ryn et al., 2015). The aim of the present study was to explore student perceptions of stereotype content in the University of Auckland’s FMHS health professional education environments’ characterisations of Māori. The primary research question was, ‘How do undergraduate nursing, pharmacy and medical students perceive characterisations of Māori in their educational environments?’

II. METHODS

A. Participants

A purposive sample of undergraduate nursing, pharmacy and medical students (N = 628) in the University of Auckland’s FMHS were invited to participate.

B. Procedure

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee. Students were sent an email invitation one week prior to data collection via paper survey. The principal researcher visited each of the five student cohorts’ lectures during Semester One of the 2014 Academic Year to conduct the cross-sectional survey.

C. Measures

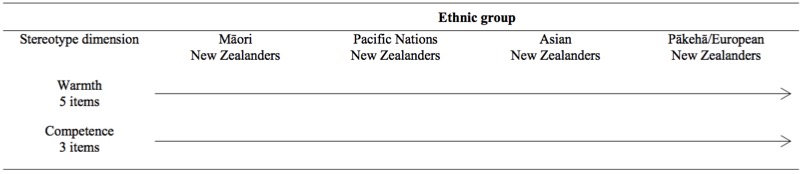

1) Stereotype content in learning environments:The questionnaire was based on the SCM (Fiske et al., 2002) and a New Zealand-based study examining societal stereotypes of Māori, Pacific Nations, Pākehā/European and Asian New Zealanders (Sibley et al., 2011).

The questionnaire was organised into four sections: 1) Māori New Zealanders, 2) Pacific Nations New Zealanders, 3) Asian New Zealanders, and 4) Pākeha/European New Zealanders. For each section, students were asked to complete eight stereotype content ratings on a five-point Likert scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) that were presented in the following question stem:

How …(warm, likeable, sincere, good-natured, tolerant, competent, intelligent, confident) is this group, as characterised in your learning environments?

The SCM surveys and Sibley et al.’s (2011) survey asked respondents “How… is this group, as viewed by society?” This research project modified the question stem in order to reflect the specific research question and aims.

2) Demographic information:The questionnaire included several items pertaining to participants’ programme of study and demographic characteristics: 1) Programme of study (nursing, pharmacy or medicine); 2) Year of programme; 3) Age in years; 4) Sex; 5) Ethnicity. For data analysis purposes, five participant ethnicity groups were categorised: Māori, Pacific Nations, Asian, Pākehā/NZ European, and Other. It is important to note that the categories Pacific Nations, Asian, and Other are not ethnic groups in themselves, but aggregations of a number of ethnic identities.

Table 1. Study design

Table 1. Study design

D. Data Analysis

First, the response rate (n/N) and participants’ demographic characteristics were presented with descriptive statistics. The internal reliability of the five items measuring warmth and the three items measuring competence, respectively, were assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Measures of central tendency in reference to Māori, Pacific Nations, Asian and Pākehā/European New Zealanders’ relative warmth and competence characterisations were determined. In accordance with the study design (Table 1), a 4 (racial/ethnic group: Māori, Pacific Nations, Asian, Pākehā/Europeans) x 2 (stereotype dimension: warmth, competence) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. Post hoc analyses were conducted to examine the extent to which ethnic group characterisations were viewed consistently among participants from each student cohort, various ethnic identities, age group, and sex.

III. RESULTS

A. Response Rate and Participant Data

A total of 444 (response rate = 71%) student surveys were completed and analysed. The nursing, pharmacy and medical student cohorts each contributed approximately one-third of all responses (nnursing= 160, 36%; npharmacy= 149, 34%; nmedicine= 135, 30%). A majority of participants were 24 years old or younger (n = 389, 88%). A majority of the participants identified themselves as female (n = 318, 72%). Participants who identified as belonging to Asian ethnicities comprised 44% (n = 197) of the total sample. Pākehā/NZ European participants were the second most represented ethnic group at 34% (n = 150). Māori participants comprised 7% (n = 31) of all respondents. 5% (n = 22) of participants identified as Pacific Nations peoples, and 10% of participants made up the ‘Other’ category, which included Middle Eastern and African ethnicities. The sample was representative of the student population that was invited to participate. The 71% response rate and sample representativeness indicate that non-response bias was effectively minimised.

B. Internal Consistency Measures

The Cronbach’s alpha (α) internal reliability coefficients for the items assessing warmth-related characterisations of Māori (α = .86), Pacific Nations peoples (α = .90), Asian peoples (α = .87) and Pākehā/European (α = .86), were acceptable (Field, 2005). Internal reliability coefficients for the items assessing competence-related characterisations were generally acceptable, with coefficients of Māori (α = .76), Pacific Nations peoples (α = .83), Asians peoples (α = .65) and Pākehā/European (α = .79). The coefficient for Asian New Zealanders was lower than the recommended .7 cut-off score.

C. Warmth and Competence Characterisations

The 4 (target ethnic group: Māori; Pacific Nations; Asian; Pākehā/European) x 2 (stereotype dimension: warmth, competence) repeated measures ANOVA generated some significant findings. An overall significant interaction was observed, Wilks’ Lambda = .47, F(3,441) = 168.40, p < .001.

| Target Ethnic Group | Warmth | Competence | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Māori | 3.55 | .64 | 3.31 | .72 |

| Pacific Nations | 3.73 | .69 | 3.32 | .73 |

| Asian | 3.28 | .71 | 3.90 | .65 |

| Pākehā/European | 3.57 | .61 | 4.02 | .57 |

Note: The mean score reflects participants’ ratings on a 5-point Likert scale.

Table 2. Mean and standard deviation (SD) ratings for the variables warmth and competence by target ethnic group

(N = 444)

Two one-way ANOVAs were conducted to assess perceptions of warmth and competence characterisations by target ethnic group separately. The overall Wilks’ Lambda tests of significance yielded several significant findings. First, differences in mean levels of perceived competence characterisations by target ethnic group were significant, Wilks’ Lambda = .52,F(3,441) = 135.25, p < .001. Second, mean levels of perceived warmth characterisations for each ethnic group were significantly different, Wilks’ Lambda = .77, F(3,441) = 42.91, p < .001. The mean warmth and competence ratings are presented in Table 2.

Using Bonferroni-adjusted alpha levels of .008 (.05/6) to minimise type I error, paired-samples t-tests were conducted and are presented in Table 3 (Bland & Altman, 1995).

D. Influence of Participant Demographic Variables

1) Programmes of study: Multivariate analyses (MANOVA) indicated that students within different programmes of study made different warmth and competence (domains) attributions across the questionnaire’s four target ethnic groups (sections). The overall multivariate analysis results showed significant main effects for sections, F(3,439) = 50.16, p < .001 and domains, F(1,441) = 41.46, p < .001. Two-way significant interaction effects were noted for sections and course of study, F(6,878) = 5.61, p < .001, domains and course of study, F(2,441) = 5.54, p < .01 and domains and sections, F(3,439) = 172.30, p < .001. A three-way significant interaction effect was noted for sections, domains, and course of study, F(6,878) = 2.43, p < .05.

2) Ethnicity:Overall the results showed significant main effects for sections, F(3,437) = 21.02, p < .001 and domains, F(1,439) = 31.25, p < .001. Two-way significant interaction effects were noted for sections and student ethnicity, F(12,1156) = 6.56, p < .001, domains and student ethnicity, F(4,439) = 2.56, p < .05 and domains and sections, F(3,437) = 108.77, p < .001. A three-way significant interaction effect was noted for sections, domains and student ethnicity, F(12,1156) = 2.01, p < .05. The findings suggest that participant ethnicity affected perceptions of warmth and competence ratings across the four sections. The descriptive data for Māori warmth and competence ratings by participant ethnicity are illustrated in Table 4.

The descriptive statistics (Table 4) indicated that characterisations of Māori were perceived differently among students from different ethnic groups. Māori students rated characterisations of Māori warmth lower than students belonging to Pacific Nations, Pākeha/NZ European and Other ethnicities. Māori students rated characterisations of Māori competence as lower than those of the four other participant groups. Students who self-identified as belonging to Pacific Nations ethnicities rated warmth and competence characterisations of Pacific Nations peoples higher than characterisations of Māori. Students belonging to Asian ethnicities rated characterisations of Māori warmth higher than characterisations of Asian peoples, but rated characterisations of Asian peoples’ competence higher than Māori. Pākehā/NZ European students rated characterisations of Māori warmth and Pākeha warmth similarly, but rated Pākehā/NZ European competence characterisations higher than those of Māori.

| Paired Differences | |||||||

| Mean | SD |

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

|||||

| Lower | Upper | t | df | ||||

| Competence | Māori vs. Asian* | -0.59 | 0.86 | -0.67 | -0.51 | -14.46 | 443 |

| Māori vs. Pākehā/NZ European* | -0.71 | 0.78 | -0.78 | -0.63 | -19.03 | 443 | |

| Māori vs. Pacific Nations | -0.01 | 0.52 | -0.06 | 0.04 | -0.37 | 443 | |

| Asian vs. Pākehā/NZ European* | -0.12 | 0.73 | -0.18 | -0.05 | -3.40 | 443 | |

| Asian vs. Pacific Nations* | 0.58 | 0.89 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 13.76 | 443 | |

| Pākehā/NZ European vs. Pacific Nations* | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.62 | 0.77 | 18.28 | 443 | |

| Warmth | Māori vs. Asian* | 0.27 | 0.83 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 6.75 | 443 |

| Māori vs Pākehā/ NZ European | -0.02 | 0.75 | -0.09 | 0.05 | -0.68 | 443 | |

| Māori vs. Pacific Nations* | -0.18 | 0.57 | -0.24 | -0.13 | -6.78 | 443 | |

| Asian vs. Pākehā/NZ European* | -0.29 | 0.81 | -0.37 | -0.21 | -7.54 | 443 | |

| Asian vs. Pacific Nations* | 0.45 | 0.90 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 10.58 | 443 | |

| Pākehā/NZ European vs. Pacific Nations* | 0.16 | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 4.01 | 443 | |

Note: *p < .008

Table 3. Paired-samples t-test: Differences in and ratings among target ethnic groups

| Participant Ethnicity | |||||

| Domains | Māori | Pacific Nations | Asian | Pākehā/NZ European | Other |

| Māori Warmth | 3.48 (.66) | 3.62 (.63) | 3.45 (.60) | 3.67 (.64) | 3.60 (.67) |

| Māori Competence | 3.04 (.81) | 3.61 (.83) | 3.25 (.63) | 3.39 (.75) | 3.38 (.75) |

| Pacific Nations Warmth | 3.67 (.59) | 4.08 (.64) | 3.50 (.72) | 3.97 (.59) | 3.80 (.63) |

| Pacific Nations Competence | 3.00 (.80) | 3.65 (.93) | 3.21 (.68) | 3.46 (.72) | 3.40 (.72) |

| Asian Warmth | 3.01 (.72) | 3.52 (.83) | 3.41 (.65) | 3.17 (.72) | 3.17 (.72) |

| Asian Competence | 3.87 (.69) | 4.32 (.67) | 3.94 (.60) | 3.79 (.69) | 3.92 (.61) |

| Pākehā/ NZ European Warmth | 3.48 (.60) | 3.53 (.63) | 3.57 (.61) | 3.67 (.60) | 3.34 (.54) |

| Pākehā/ NZ European Competence | 4.05 (.51) | 4.11 (.58) | 4.04 (.59) | 4.01 (.55) | 3.89 (.55) |

Table 4. Target ethnic group mean (SD) ratings for warmth and competence by participant ethnicity

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Main Finding

This study’s main finding is that undergraduate nursing, pharmacy and medical students perceived unequal warmth and competence characterisations (stereotype content) based on target ethnicity (Māori, Pacific Nations, Asian and Pākehā/European) in their learning environments. Curtis et al. (2012) reported Māori students’ perspectives on the University of Auckland’s FMHS, and negative stereotypical caricatures were one aspect. This study’s main finding expands this point, demonstrating that a broad sample of students, both Māori and non-Māori, detect differential stereotype content pertaining to Māori in their FMHS learning environments. This finding is significant and has implications for three interrelated aspects of medical and health sciences education at the University of Auckland: 1) students’ Hauora Māori educational outcomes, 2) graduates’ subsequent clinical practice and their capacity to provide equitable care, and 3) Māori student recruitment, retention and impacts on the Māori health workforce.

First, an educational environment that expresses low to moderate warmth and competence characterisations of Māori in formal instruction sites (e.g. lecture theatres) or tacitly endorses these attitudes in more informal learning sites (e.g. conversations in student study groups) is fundamentally incongruent with the (formal) Hauora Māori curriculum, a core component of health professional education programmes (Jones, 2011). One curricular objective at the University of Auckland is that all FMHS graduates will actively challenge racism (Jones, 2011). If the University’s learning spaces are complicit in the maintenance of racist ideologies, students and graduates will be less well equipped to challenge racism.

An educational environment that conveys low to moderate warmth and competence among Māori may influence future healthcare providers’ expectations and subsequent behaviours/actions during clinical encounters. Moskowitz, Stone and Childs (2012, p. 997) advise that stereotypes “arm” healthcare providers with expectations about patients and that unconscious stereotype activation has been demonstrated to influence perception, judgement, evaluation and behaviour. Harris et al.’s (2018) recent study indicates that it is yet unclear the degree to which formal and informal learning inform students’ conscious and unconscious racial bias and clinical decision making with respect to Māori, however further investigations are necessary.

Third, the University of Auckland has made commitments to increase recruitment and training of Māori health professionals (Curtis et al., 2014). The presence of negative racial stereotypes in tertiary education has a direct impact on the experiences and performance of students and faculty belonging to marginalised racial and ethnic populations (Diggs, Garrison-Wade, Estrada, & Galindo, 2009; Massey & Fischer, 2005; Mayeda, Keil, Dutton, & Ofamo¢Oni, 2014; Rankin & Reason, 2005).

B. Comparison to National Stereotype Content Study

Sibley et al. (2011) applied the SCM to the New Zealand racial and ethnic context. Sibley et al.’s (2011) results aligned with SCM-derived hypotheses. When the national study results are compared to the present study, two divergent findings are evident, indicating that student perceptions of stereotype content in the University of Auckland’s FMHS learning environments differ from the wider New Zealand context.

The SCM predicts that society’s dominant social groups are portrayed as highly warm and competent compared to traditionally marginalised populations (Fiske et al., 2002). Student perceptions of Māori warmth (as characterised in FMHS learning environments) were not significantly different from perceptions of Pākehā/NZ European warmth. When this study’s relative warmth ratings (based on perceptions of characterisations) are viewed by participant ethnicity, Māori and Pākehā/NZ European participants’ ratings of Māori and Pākehā/NZ European New Zealanders are equivalent. This indicates that Māori and Pākehā/NZ European students perceive that characterisations of Māori warmth and Pākehā warmth in their learning environments are the same. Further investigations are required before inferences or conclusions may be drawn with respect to this finding.

Participants’ comparable ratings of Māori and Pacific Nations competence characterisations are also noteworthy in view of the national study results and SCM predictions that Māori competence would be rated as higher than Pacific Nations competence (Sibley et al., 2011). This finding may be connected to frequent referrals in New Zealand health literature to ‘Māori and Pacific’ as a pair. The pairing is reiterated within the University of Auckland’s FMHS with respect to the Māori and Pacific Admission Scheme (MAPAS), the restorative justice programme initiated in the 1970s that aims to increase the Māori and Pacific Nations health workforce (Curtis et al., 2014). ‘MAPAS’ is used as an adjective on campus to describe both individuals (e.g. MAPAS coordinator) and groups (e.g. MAPAS students; The University of Auckland, 2018). While Curtis et al. (2014) clarify a historically and culturally contextualised rationale for discussing Māori and Pacific Nations peoples’ health together, an unintended consequence of the repetitive pairing may be the conflation or homogenisation of Māori and Pacific Nations peoples and priorities.

Literature pertaining to unconscious bias in health care argues that clinicians’ capacity to perceive and connect with patients as unique individuals, rather than group members, is key to combating discriminatory practices (Burgess, van Ryn, Dovidio, & Saha, 2007). A repeated conflation or homogenisation of Māori and Pacific Nations peoples, when discussing population health and racial disparities in health/health care, may be at odds with developing students’ skills for overcoming personal bias and reducing discrimination during interpersonal clinical encounters. This tension is interesting because educators delivering health equity curricula to medical and health science students state that it is important for students to understand the structural and social determinants of population health disparities (Betancourt, 2006), determinants that cause similar vulnerabilities among Māori and Pacific Nations peoples.

C. Māori Student Perspectives

Māori students were the only participant group to rate warmth and competence characterisations of their own identity group lower (on average) than members of other groups. Acute awareness among Māori students of the presence of negative attitudes in their learning environments may account for this result. This finding aligns with several articles that identify New Zealand universities as spaces with institutional norms and values that reflect the Pākehā/NZ European hegemony and marginalise Māori (Mayeda et al., 2014; Santamaría, Lee, & Harker, 2014).

V. CONCLUSION

Jones et al. (2019) articulate clear directives for medical education institutions to enact “indigenised,” decolonised, anti-racist health professional education, training and health system transformation. Developing localised knowledge of institutions’ ‘informal’ and ‘hidden’ curricula and the ways in which they function in opposition to formal Indigenous health curricula is key to developing an aligned institutional curriculum. In addition to Jones et al.’s (2019) recommendation that structured frameworks such as the Critical Reflection Tool be used to facilitate institutional reflexivity, criticality and reform, investigations into student perceptions of stereotype content could serve as an educational tool to aid students in recognising and taking responsibility for the ways in which colonisation, racism and privilege function in their educational environments.

The study’s sample size (n = 444) and response rate (71%) were strengths of the study. The cross-sectional survey design was both a strength and limitation of the study. The design’s strength lay in the anonymous questionnaire’s capacity to minimise social desirability bias while capturing a broad range of student perspectives. A limitation of the design was that data collection occurred during a distinct moment in time. Students participated in the study during the first few weeks of Semester One, 2014. If students had been surveyed following longer periods of exposure to the language and attitudes of their learning environments, the results may have been quite different. Another limitation of the study is its inability to ascertain whether students’ choices on the quantitative questionnaire items were influenced most by formal learning environments or students’ experiences in other settings.

In summary, our study demonstrated that undergraduate nursing, pharmacy, and medical students in the University of Auckland’s FMHS perceive unequal characterisations of warmth and competence across four target ethnic groups in their learning environments. Student perceptions of characterisations of Māori indicate the presence of negative stereotyping, which is incongruent with the formal Hauora Māori curriculum. Our inventory of stereotype content in health professional learning environments, as perceived by students, provides empirical evidence for important aspects of hidden/informal curricula. Future studies should attempt to identify the sources of student perceptions.

Notes on Contributors

Caitlin Harrison was a successful postgraduate student whose thesis was submitted as part of the degree of Master of Public Health at the University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Rhys Jones is a Senior Lecturer in Te Kupenga Hauora Māori (the Department of Māori Health) at the University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Marcus A. Henning is an Associate Professor in the Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education at the University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Ethical Approval

Approval was obtained by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee, reference number 010926.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the University of Auckland, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences and the study participants for making this project possible.

Funding

This is an unfunded study.

Declaration of Interest

All authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

Aronson, J., Burgess, D., Phelan, S. M., & Juarez, L. (2013). Unhealthy interactions: The role of stereotype threat in health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(1), 50-56.

Betancourt, J. R. (2006). Eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in health care: What is the role of academic medicine? Academic Medicine, 81(9), 788-792.

Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (1995). Multiple significance tests: The Bonferroni method. British Medical Journal, 310(6973), 170.

Burgess, D., van Ryn, M., Dovidio, J., & Saha, S. (2007). Reducing racial bias among health care providers: Lessons from social-cognitive psychology. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(6), 882-887.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 61-149.

Curtis, E., Reid, P., & Jones, R. (2014). Decolonising the academy: The process of re-presenting indigenous health in tertiary teaching and learning. Diversity in Higher Education, 15, 147-165.

Curtis, E. T., Wikaire, E., Lualua-Aati, T., Kool, B., Nepia, W., Ruka, M., … Poole, P. (2012). Tātou tātou/Success for all: Improving Māori student success. Retrieved from https://ako.ac.nz/assets/Knowledge-centre/NPF-08-002-Tatou-Tatou-Success-for-all-Improving-Maori-student-success/52178cfd54/RESEARCH-REPORT-Tatou-Tatou-Success-For-All-Improving-Maori-Student-Success.pdf

Diggs, G. A., Garrison-Wade, D. F., Estrada, D. E., & Galindo, R. (2009). Smiling faces and colored spaces: The experiences of faculty of color pursing tenure in the academy. The Urban Review, 41(4), 312-333.

Dovidio, J. F., & Fiske, S. T. (2012). Under the radar: How unexamined biases in decision-making processes in clinical interactions can contribute to health care disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 945-952.

Field, A. P. (2005). Discovering statistics using SPSS: And sex, drugs and rock’n’roll(2nd ed.). London, England: SAGE Publications.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878-902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

Hafferty, F. W. (1998). Beyond curriculum reform: Confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Academic Medicine, 73(4), 403-407.

Harris, R., Cormack, D., Stanley, J., Curtis, E., Jones, R., & Lacey, C. (2018). Ethnic bias and clinical decision-making among New Zealand medical students: An observational study. BioMed Central Medical Education, 18(1), 18-29.

Harris, R., Cormack, D., Tobias, M., Yeh, L., Talamaivao, N., Minster, J., & Timutimu, R. (2012). The pervasive effects of racism: Experiences of racial discrimination in New Zealand over time and associations with multiple health domains. Social Science & Medicine, 74(3), 408-415.

Hill, S., Sarfati, D., Robson, B., & Blakely, T. (2013). Indigenous inequalities in cancer: What role for health care? ANZ Journal of Surgery, 83(1-2), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.12041

Howe, A. (2002). Professional development in undergraduate medical curricula – The key to the door of a new culture? Medical Education, 36(4), 353-359.

Jansen, P., & Jansen, D. (2013). Māori and health. In I. St George (Ed.), Cole’s medical practice in New Zealand(12th ed., pp. 52-65). Wellington, New Zealand: Medical Council of New Zealand.

Jones, R. (2011). Te Ara: A pathway to excellence in Indigenous health teaching and learning. Focus on Health Professional Education, 13(1), 23-34.

Jones, R., Crowshoe, L., Reid, P., Calam, B., Curtis, E., Green, M., … Ewen, S. (2019). Educating for indigenous health equity: An international consensus statement. Academic Medicine, 94(4), 512-519.

Jones, R., Pitama, S., Huria, T., Poole, P., McKimm, J., Pinnock, R., & Reid, P. (2010). Medical education to improve Māori health. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 123(1316), 113-122.

Massey, D. S., & Fischer, M. J. (2005). Stereotype threat and academic performance: New findings from a racially diverse sample of college freshmen. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 2(1), 45-67.

Mayeda, D. T., Keil, M., Dutton, H. D., & Ofamo¢Oni, I. (2014). “You’ve gotta set a precedent”: Māori and Pacific voices on student success in higher education. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 10(2), 165-179.

McCreanor, T., & Nairn, R. (2002). Tauiwi general practitioners’ explanations of Māori health: Colonial relations in primary healthcare in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Journal of Health Psychology, 7(5), 509-518.

Ministry of Health. (2015, November 13). Mortality and demographic data 2012. Retrieved from https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/mortality-and-demographic-data-2012

Moskowitz, G. B., Stone, J., & Childs, A. (2012). Implicit stereotyping and medical decisions: Unconscious stereotype activation in practitioners’ thoughts about African Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 996-1001.

Paul, D., Ewen, S. C., & Jones, R. (2014). Cultural competence in medical education: Aligning the formal, informal and hidden curricula. Advances in Health Science Education, 19(5), 751-758.

Penney, L., Barnes, H. M., & McCreanor, T. (2011). The blame game: Constructions of Māori medical compliance.AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 7(2), 73-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011100700201

Rankin, S. R., & Reason, R. D. (2005). Differing perceptions: How students of color and white students perceive campus climate for underrepresented groups. Journal of College Student Development, 46(1), 43-61.

Santamaría, L. J., Lee, J. B. J., & Harker, N. (2014). Optimising Māori academic achievement (OMAA): An indigenous-led, international, inter-institutional higher education initiative. In Māori and Pasifika higher educationhorizons (Volume 15). Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 201-220. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-364420140000015018

Sibley, C. G., Stewart, K., Houkamau, C., Manuela, S., Perry, R., Wootton, L. W., … Asbrock, F. (2011). Ethnic group stereotypes in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 40(2), 25-36.

Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa. (2015, May 8). New Zealand period life tables: 2012-14. Retrieved from https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/new-zealand-period-life-tables-201214

The University of Auckland. (2018). About MAPAS. Retrieved from https://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/fmhs/study-with-us/maori-and-pacific-at-the-faculty/maori-and-pacific-admission-schemes.html

van Ryn, M., Burgess, D. J., Dovidio, J. F., Phelan, S. M., Saha, S., Malat, J., … Perry, S. (2011). The impact of racism on clinician cognition, behavior, and clinical decision making. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 8(1), 199-218.

van Ryn, M., Hardeman, R., Phelan, S. M., Burgess, D. J., Dovidio, J. F., Herrin, J., … Przedworski, J. M. (2015). Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3547 students: A medical student CHANGES study report. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(12), 1748-1756.

Williams, D. R., & Mohammed, S. A. (2013). Racism and health II: A needed research agenda for effective interventions. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1200-1226.

Wilson, D., & Barton, P. (2012). Indigenous hospital experiences: A New Zealand case study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(15-16), 2316-2326.

*Caitlin Harrison

155 North Road, St Andrews,

Bristol BS6 5AH, United Kingdom

E-mail: ctlnharrison@gmail.com

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.