Improving provider-patient communication skills among doctors and nurses in the children’s Emergency Department

Submitted: 25 May 2019

Accepted: 18 February 2020

Published online: 1 September, TAPS 2020, 5(3), 28-41

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-3/OA2160

Su Ann Khoo, Warier Aswin, Germac Qiao Yue Shen, Hashim Mubinul Haq, Badron Junaidah, Jinmian Luther Yiew, Mahendran Abiramy & Ganapathy Sashikumar

Children’s Emergency Department, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Effective communication is of paramount importance in delivering patient-centred care. Effective communication between the healthcare personnel and the patient leads to better compliance, better health outcomes, decreased litigation, and higher satisfaction for both doctors and patients.

Objective: The objective of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a comprehensive blended communication program to improve the communication skills and the confidence level of all staff of a department of emergency medicine in Singapore in dealing with challenging communication situations.

Methods: All doctors and nurses working in the selected Children’s Emergency Department (ED) attended blended teaching to improve communication skills. Qualitative feedback was gathered from participants via feedback forms and focus group interviews. Communication-related negative feedback in the ED was monitored over a period of 18 months, from 1st July 2017 to 31st December 2018.

Results: Immediately after the course, 95% of the participants felt that they were able to better frame their communications. Focus group interviews revealed four main themes: (A) Increased empowerment of staff; (B) Improved focus of communication with parents; (C) Reduced feeling of incompetence when dealing with difficult parents and; (D) Increased understanding of main issues and parental needs. There was 81.8% reduction in communication-related negative feedback received in the ED monthly after the workshop had been carried out (95% confidence interval 0.523, 0.8182).

Conclusion: A comprehensive blended communication workshop resulted in a perceived improvement of communication skills among the healthcare personnel and significantly decreased the communication-related negative feedback in a pediatric ED.

Keywords: Communication, Blended Learning, Patient-Centred Care, Children’s Emergency Department

Practice Highlights

- Effective communication is paramount in good physicians, nurses and allied health practices.

- A comprehensive blended learning communication workshop improves the communication skills and confidence among all levels of staffs in Children’s Emergency.

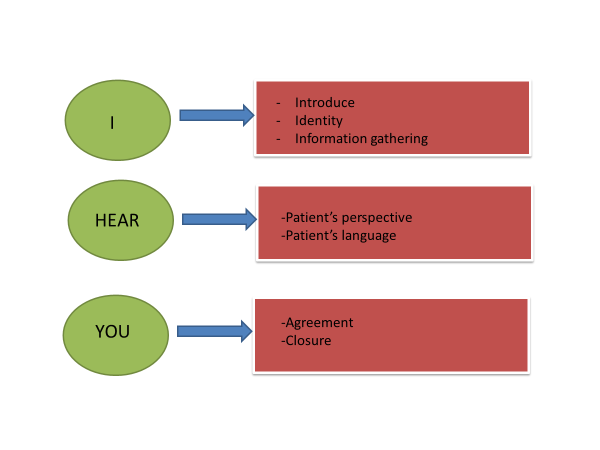

- “I Hear You” contains essential elements of effective communication and helped learners to remember while handling difficult communication-related scenarios.

- Patient-centric communication workshop reduced communication-related complaints in the Children’s Emergency.

I. INTRODUCTION

Cultivating the skill of effective communication is a vital component in the training of all healthcare personnel. Good communication skills are an essential component of healthcare and allied health. Effective communication between the doctor and the patient leads to better compliance, better health outcomes, decreased litigation, and higher satisfaction for both doctors and patients (Deveugele et al., 2005; Rider, Hinrichs, & Lown, 2006). In the emergency setting, this would reduce the number of reattendances, which in turn leads to better use of resources and reduce the burden of the Emergency Department (ED; Shendurnikar & Thakkar, 2013). Some of the barriers to good healthcare personnel to patient communication include the usage of medical jargons, inability to communicate in simple language, inappropriate use of body language, lack of time dedicated to communicating during the staff-patient encounter and frequent interruptions (Rowland-Morin & Carroll, 1990).

A large proportion of negative feedback given by patients towards healthcare providers–between 60% to 75%–is related to communication lapses (Krishel & Baraff, 1993; Lau, 2000; Rhee & Bird, 1996; Thompson & Yarnold, 1996). While reviewing 122 complaints received in the ED over 7 years, Hunt and Glucksman (1991) noted that the commonest cause of complaint was on attitude (37.7%) and poor communication accounted for 30% of it. In the Children’s ED, working with the Office of Patient Experience (OPE), we found a pattern of increasing communication-related negative complaints which prompted the initiation of the workshop and this study.

The goal of this communication workshop was to improve the communication skills, increase the level of confidence amongst emergency medicine personnel in dealing with communication issues and to reduce communications related patient feedback in the Children’s ED. This communication training programme was designed to address the issue of an increasing number of complaints received due to communication lapses among doctors and patients between July 2016 and June 2017. The objective of this workshop was to design and implement a curriculum to effectively teach, deliver and reinforce effective communication skills among doctors and nurses in a busy ED. The advantages of blended learning formats are: They are valued by self-directed adult learners; help overcome limitations of adequate time and space; able to reach a larger number of students; save training costs; produce high student ratings; increase student perceptions of achieving course objectives; and have achieved academic results equivalent to strict face-to-face teaching (Ausburn, 2004; Gray & Tobin, 2010).

The aim of this study is to create an interprofessional communication workshop for the ED to reduce communication-related complaints. Secondly, the study also aims to introduce blended learning in the communication workshop, evaluating and understanding its impact as a teaching tool in the ED.

II. METHODS

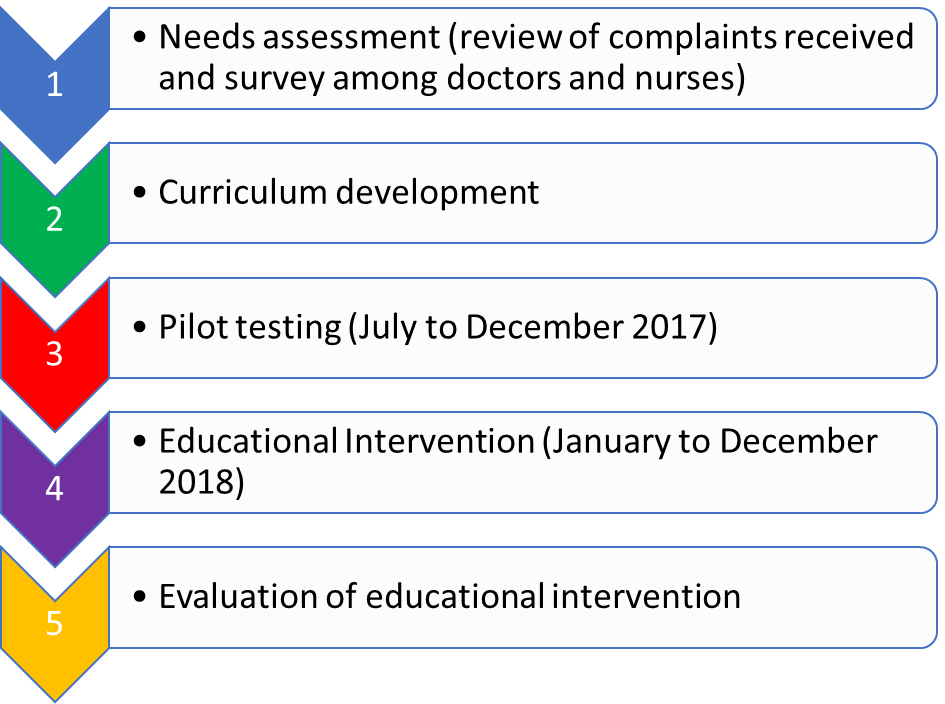

The study of the workshop was conducted in five stages: (A) Needs assessment, (B) Curriculum development, (C) Pilot testing, (D) Educational intervention, and (E) Evaluation of the intervention (illustrated in Figure 1).

The research team reviewed complaints and compliments received in the Children’s ED over the 12 months preceding to implementation of this workshop. We then derived a list of the commonest complaint themes that guided the curricula development of this communication workshop. In a previous study by Mehta (2008), reviewing patients’ emails and feedback forms helped to identify training needs (Mehta, 2008; Rowland-Morin & Carroll, 1990; Shendurnikar & Thakkar, 2013). A needs assessment was also conducted among the doctors and nurses working in the Children’s ED.

Based on the literature, surveys and review of complaints, we chose four main themes for the development of the curriculum content. They were (A) Perception of waiting time and handling of dissatisfied patients, (B) Information delivery and expressive quality, (C) Physician’s attitude and lack of empathy/ inappropriate use of body language, and (D) Physician’s explanation of illness and treatment–these are all in keeping with the numerous studies that have been done on factors affecting patient satisfaction in ED (Krishel & Baraff, 1993; Lau, 2000; Rhee & Bird, 1996; Thompson & Yarnold, 1996). These studies focus on the perceived technical quality of care, perception regarding waiting time, information delivery and expressive quality, ED information received, health professional’s attitude, health professional’s explanation of illness and treatment and ease and convenience of care. These themes were applied in the creation of our video-based scenarios, real simulation scenarios during the workshop and delivery of lectures, as well as the development of our very own concept of ‘I Hear You’ (illustrated in Figure 2). Communication scenarios are ED-specific, and this has been given serious consideration and adapted to our multilingual and multicultural community. The needs will be addressed not only based on these themes, but the multisource and focus group survey received from doctors and nurses as previously mentioned.

We used a mixed-method design to develop the curriculum and evaluate the impact of this communication workshop; a similar method used by De Feijter, De Grave, Dornan, Koopmans, and Scherpbier (2011), utilising results from an evaluation questionnaire, data of communication-related complaints obtained from the OPE and focus groups to gauge the impact and learning experiences of the participants from the workshop.

A. Figures

Figure 1. Five stages in the study

Figure 2. “I Hear You” concept; representing the 6 essential elements of effective communication

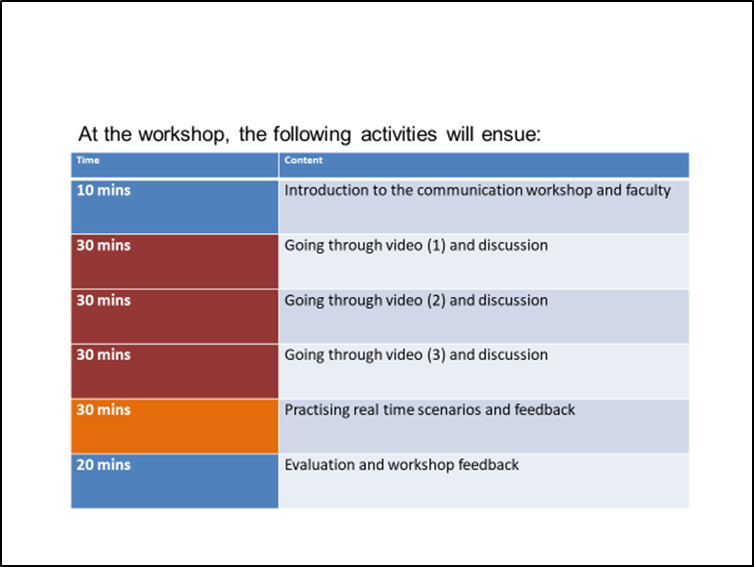

Figure 3. Timings allocated during the face-to-face workshop

The delivery of the curriculum and contents were based on blended learning.

There were two main parts in the educational intervention; A) a pre-workshop web-based, self-directed, learning module with videos on five different scenarios, followed by B) a three-hour tutor-guided workshop. The workshop consisted of sessions going through scenarios in the videos, real face-to-face session with simulated patients, and small group feedback session with content specialists. The themes of the five main scenarios were: (a) long waiting time, (b) lost full blood count sample, (c) patient education, (d) medication error, and (e) patient management and delivery of medications. During simulation practices, three participants were involved. Each will be given a sheet of paper with different roles to play; one as the doctor or nurse, one as the patient and one as the observer. Each participant received different sheets of paper with instructions to the role player and scenario involved. (Refer to Appendix). Each workshop was conducted by 2 facilitators: 1 from Medical (Senior doctors) and 1 from Nursing (Nurse clinicians and senior staff nurses). The workshops were conducted on a weekly basis, on every Tuesday, for three hours (refer to Figure 3 for the details of 3-hour workshop utilisation). A total of 185 doctors (Resident Physicians, Residents and Medical officers), and 110 nurses were trained over the 16 months period and each of the personnel attended one of the 68 iterations of the workshop. The schedule was coordinated and planned into the roster for both nurses and doctors who were working on shifts. A facilitator guidebook was put together as a reference for all facilitators and to ensure standardisation of the delivery of teaching. The guidebook contained the specific objectives, scenarios and feedback questionnaires.

We monitored feedback from both patients in the ED regarding the quality of communication among doctors and nurses, working in the department after this workshop had been implemented, with the help of OPE. The effect of this workshop on patients’ satisfaction and learners’ improvement were assessed retrospectively in two ways: (1) Number of complaints received based on communication skills and attitude of medical staffs before and after the series of workshop; (2) Learners’ perception and confidence in handling difficult scenarios in the ED before and after the series of workshops. There are regular patients’ satisfactory surveys in the ED, and these questionnaires are distributed to patients after their encounter in the ED. Patients were encouraged to return the forms before formal discharge from the ED, via a box, or to email the Office of Patient Experience directly. There were also service staffs on the ground who provided help and received direct feedback from patients and caregivers. The number of complaints received pre-workshop and during pilot testing were compared with post-workshop. The confidence interval of a proportion was calculated using the Wilson procedure without a correction for continuity.

An effective or positive communication-related encounter consisted of four important elements: (A) Approach, (B) Manner, (C) Techniques in Interaction and (D) Verbal and non-verbal communication cues including eye contact, touch, as well as management of space (O’Hagan et al., 2014). Feedback was categorised as communication-related negative feedback when any of the important elements mentioned above were reported as inadequate or missing in the complaints by patients or caregivers. The evaluation of the workshop consisted of focus group sessions and feedback forms. All the participants filled a feedback form at the end of every workshop session.

Six focus group sessions were conducted. The grouping for the focus group sessions is mixed between doctors and nurses. These focus groups involved a total of 25 doctors and 15 nurses. These doctors were drawn from three different residencies (Family Medicine, Emergency Medicine, Paediatric Medicine), medical officers and resident physicians in the ED. The nurses were all from the Children’s ED. The criteria of selection were based on a purposive sampling of participants across age groups, seniority and experience levels. Informed consent were obtained from all the participants. The focus group discussion scripts were analysed using thematic analysis to identify themes in the participants’ feedback on how the workshop had helped them. The coding of the data was done independently by two reviewers and this was compared. Any differences in opinion were discussed with a third reviewer to achieve an agreeable and suited conclusion.

The trustworthiness of the data analysis and collection was ensured using data and investigator triangulation. Multiple focus groups were held with different groups of people. In terms of investigator triangulation, the coding was performed by two independent people as mentioned earlier. When a certain code or theme was unclear, or the investigator had clarifications with regards to the interviews in focus groups, the investigator went back to that particular individual to clarify their thoughts and views.

III. RESULTS

The needs assessment amongst nurses and junior doctors in the department showed that 70% are not confident in dealing with difficult situations and 90% have not received formal training in communication skills. They felt that there was a compelling need for a formal communications course to teach them skills and techniques in dealing with difficult situations and breaking bad news, a correct way to deliver information to parents and patients after consultation as well as addressing a dissatisfied parent on the long waiting time. Feedback gathered among patients attending the Children ED also indicated that the communication style and skills can be improved to improve the delivery of patient-centric care.

A review of the complaints received in the Children’s ED over the 12 months preceding to implementation of this workshop revealed that 73% of the complaints were communication-related. These complaints were collated directly by the OPE. The top 5 communication-related complaints revolved around long waiting time, lack of synchronisation in the explanation given between different doctors and nurses, clotting of blood samples, medication errors and explanation given to patients by doctors or nurses regarding their conditions.

The pilot testing was carried in the period of 1st August 2017 to 31st December 2017.

Blended learning was received well by the staffs in the department; many described as a “breath of fresh air”, compared to the other communication workshops carried out within the institution. In the setting of Children’s ED where doctors and nurse work shift hours, blended learning provided better flexibility and better use of resources.

The participants felt that the workshop was very relevant as it is situation- and department-specific. The new staffs found the workshop helped prepared them mentally of the patients’ and caregivers’ expectations in the Children’s ED. In the educational intervention, the participants found the videos used for the scenarios were useful, and easily accessible, although there were hiccups with internet connections and equipment occasionally. The participants also provided feedback on scenarios to be added on. A small percentage of 1% commented that some of the videos were too long (the videos ranged between 5 and 7 minutes). They liked the discussion sessions after each video as it allowed them to share their own experiences and difficulties. The facilitators would provide options for handing different difficult scenarios. They also liked the simulation scenarios as it helped them to reinforce learning, and learned from others through observation and direct feedback after the sessions.

The modified concept of “I Hear You” by the team was designed to enable staffs to remember the important steps of: i) open the discussion, ii) gathering information, iii) understand patient’s perspective, iv) share information, v) reach an agreement on problems and plans and vi) provide closure. A short and easy to remember phrase like “I Hear You” was found to be useful by staffs to remind, incorporate and practise all the 6 steps of effective communication.

Immediately after the course, 95% of the participants felt that they were able to better frame their communications. Thematic analysis of the focus group revealed 4 themes: “Empowerment of staff”, “Focused communication with parents”, “Confidence in dealing with difficult parents” and “Empathy towards patients and caregivers”.

A. Empowerment of staff

A key thing in the communication among staffs (nurses and doctors) with patients and their caregivers is empowerment. Working in an intensive and highly stressful environment in the ED often leads to a high-burnout rate, and when complaints are received, staff feel that their efforts are often not good enough. The face-to-face sessions have allowed staff to share their experiences with others, and to realise that each and every individual staff member is important in contributing to the care of the patients. Attending the workshop created and reinforced increased empowerment among the participants in dealing with difficult communication situations.

“I felt more empowered when I spoke to parents.”

(Focus group No: 1/ Participant No: 3)

“The course made me feel part of the team and that I was solving issue when speaking to parents.”

(Focus group No: 2/ Participant No: 2)

“I feel like we have the responsibility and trust to speak to families and help them understand the issues faced by the child and also the team.”

(Focus group No: 3/ Participant No:2)

B. Focused communication with parents

The workshop has helped participants to realise the importance of communication to increase the efficiency within the department, focusing back to the patients rather than emotions of anxious or angry caregivers, as well as when to escalate and ask for help on difficult situations.

“I always tried to focus back on the patient rather than the unimportant issues and that helped.”

(Focus group No: 2/ Participant No: 4)

“I kept thinking back to ‘I Hear You’, and the importance of focusing on the caregiver and the message they are trying to get across.”

(Focus group No: 1/ Participant No: 1)

C. Confidence in dealing with difficult parents

The workshop helped participants realise the importance of minding body language, phrases used and the tonality of their speech while trying to communicate effectively with both patients and caregivers.

“I felt confident immediately after the course and used keywords when speaking to parents, rather than going blind.”

(Focus group No: 4/ Participant No: 1)

“At least now, I feel more equipped to handle difficult communication encounters, like I have been trained and have a mental model.”

(Focus group No: 5/ Participant No: 3)

D. Empathy towards patients and caregivers

Understanding the circumstance to the behaviour, caregivers’ beliefs, concerns and expectations of illness and treatment are important points. This allows appropriate response to patients’ and caregivers’ statements about ideas, feeling and values.

“Parents usually have valid point; we just need to figure it out and respect that.”

(Focus group No: 2/ Participant No: 1)

“I try to focus on the matter and the patient, and not take the comments personally.”

(Focus group No: 5/ Participant No: 2)

“It felt like we could truly understand what the parents wanted and see beyond the initial unhappiness.”

(Focus group No: 4/ Participant No: 4)

E. Patient Feedback

There was 81.8% reduction in communication-related negative feedback monthly in the data collected by the OPE in the period of 1st July 2017 to 31st December 2017 as compared to 1st January 2018 to 31st December 2018 (95% confidence interval; CI 0.523, 0.8182). Over this period of 17 months, there were 99 communication-related negative feedback received: 68 of these were received in the first 6 months (1st July 2017 to 31st December 2017) when the pilot workshops were carried out, and only 31 communication-related negative complaints were received in the subsequent 12 months (1st January 2018 to 31st December 2018). The number of patients seen yearly in the Children’s ED averaged about 150,000 for both 2017 and 2018 (refer to Table 1). The number of reductions of communication-related negative feedback received monthly during the pre- and post-workshop period was statistically significant. It reflected that with every 10,000 patients seen in the ED monthly, there was a reduction of nine communication-related negative feedback per month, between the pre- and post-workshop implementation period.

Table 1. Comparison of complaints received pre- and post-workshop (total period of 17 months)

IV. DISCUSSION

The findings of this study offer new insights into doctor- or nurse-patient communication because the creation of the curriculum content and delivery of the teaching are built in the values of professionals working in a busy ED, rather than extrapolated from other fields of healthcare. The scenarios and videos were created based on commonest communication-related complaints and feedback from providers on the scenarios they found most challenging.

This study revealed a further emphasis on teaching and reinforcing effective communication skills; something we took for granted that all graduates from medical school have been equipped with. Even staff who have years of experience working in the ED can become complacent and needed reminders on the importance of patient-centred communication to improve the quality of care delivered to patients. The curriculum development based on evidence, review of complaints and feedback from staffs made it relevant and relatable to participants. This is different from existing communication workshop that is more exam-oriented, or touching on general aspects of communication which emphasised mainly on steps of communication without relating to a specific scenario.

Furthermore, the approach to the delivery and running of the workshop in the form of blended learning is well-received by participants. The process of watching pre-workshop videos allows participants time to reflect on their own thoughts and encounters in similar scenarios in the ED. The facilitator-guided workshop, in small groups of six to seven participants, allowed time for reinforcement via discussion of scenarios in the videos and simulation practices. The participants are free to share their views and feedback in a safe space, within the small group. Learners also find the concept of “I Hear You” easy to remember and serves as a reminder of the six steps of a good doctor- or nurse-patient communication.

The results indicate four themes that reflect on how the workshop has helped learners personally and in developing effective patient-centric communication; empowerment, focus of communication, confidence and empathy towards patients. With advances in medical care and modern management concepts, health care institutions are moving towards patient-centred care, and aim to increase patients’ satisfaction and overall experience of clinical encounters.

One year into running the communication workshop, there was a striking 81.8% decrease in communication-related negative complaints received in the Children’s ED. More importantly, we also found that this workshop had helped to boost confidence and morale, especially among the doctors and nurses, in dealing with difficult situations.

Teachers and participants had learned that teaching a “soft skill” like communication is essential and unfortunately often overlooked because we assumed our doctors and nurses had already been well-equipped upon graduation of respective medical or nursing schools. The workshop provided a safe space for staffs to share their reflections and feedback on the video scenarios and during simulation practice of difficult communication situations in the ED. The staffs were free from distractions of involvement in interaction and were therefore in a position to provide comprehensive and reflective feedback. Learners identified important aspects of effective communication that often co-occur with one another. The feedback given by the facilitators demonstrated and helped learners realised how a lack of patient-centredness in approach underpins an absence rapport building and other behaviour associated with a positive manner towards patients.

It will be meaningful to continue tracking the progress of feedback from patients with regards to communication-related issues, as well as to follow-up with staffs who have been trained to ensure that the good practice and application of “I Hear You” continues. This workshop has continued to run to include the new doctors and nurses rotating, or working as permanent staff in the department. In time to come, we hope to extend the training in this communication workshop to allied health professionals who work directly or indirectly with the department to improve standardisation and patients’ overall experience in the Children’s Emergency. The knowledge and experience have also been shared with other EDs, with modifications suited to patient population and types of feedback received. These departments have sent observers to join our workshop sessions. We are hopeful that the approach and usefulness of this workshop continue to benefit all the healthcare providers and lead to improved care for patients.

V. LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations. The video consisted of scenarios specific to the ED, hence may not be directly applicable to other healthcare settings. A patient encounter and experience in the ED consist not only encounter with the doctors and nurses, but also with the allied healthcare professionals in the ED. There is also a lack of local studies to compare the effectiveness of similar interventions, which have been proven useful in our institution.

VI. CONCLUSION

A focused, patient-centric and blended communication workshop was found to improve the communication skills and confidence among doctors and nurses in the ED, with a corresponding increase in patients’ satisfaction and a reduction in complaints related to communication lapses. This study serves as a starting point in the local context, to bring the emphasis and importance in teaching, informing and reinforcing the important aspects of communication that clinicians and educators consider relevant for effective doctor- and nurse-patient interactions in clinical practice. This workshop also helped to orient junior doctors to what is valued by patients, experienced peers and encourage greater awareness of the impact of particular approaches and techniques to effective communication with patients and caregivers.

Notes on Contributors

Dr SA Khoo is a Staff Registrar with the Children’s Emergency Department (ED), KKH. She did the literature reviews, participated in poster and oral presentation for this project, as well as the write-up of this manuscript.

Dr Warier Aswin, Senior Staff registrar with the Children ED, KKH; Nurse Clinician Germac Shen Qiao Yue; Dr Badron Junaidah Staff Physician with the Children’s ED, KKH; and Senior staff nurses Luther Yiew Jin Mian and Mubinul Haq Hashim, helped designed the program, faculty guide and videos for the workshop.

Dr Sashikumar Ganapathy, Deputy Head and Consultant with the Children’s ED, KKH, is the overall supervisor who conceptualised the workshop, handled focus group interviews, creation of videos and faculty guide.

Dr Mahendran Abiramy and all the previous contributors mentioned above are also faculties who trained the doctors and nurses in the workshop.

Ethical Approval

This study has been reviewed and approved by our institution’s Centralised Institutional Review Board of Singhealth (CIRB) committee. The CIRB reference number is 2017/2784.

Acknowledgements

Special acknowledgement to Mr Luther Yiew Jinmian and Singhealth Academy team who helped created the videos used for the teaching and discussions in communication workshop.

We would also like to thank Dr Lee Khai Pin, Senior Consultant and Head of Children’s Emergency Department, and Dr Arif Tyebally, Senior Consultant and Deputy Head of Children’s Emergency Department, for their support in the running this program.

The team is also grateful to the team from the Office of Patient Experience for providing us with the data of negative communication-related complaints and continued to monitor that for the department.

Funding

This program initiative was funded by AMEI (Academic Medicine Education Institute) Education Grant 2017.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

Ausburn, L. J. (2004). Course design elements most valued by adult learners in blended online education environments: An American perspective. Education Media International, 41(4), 327-337.

De Feijter, J. M., De Grave, W. S., Dornan, T., Koopmans, R. P., & Scherpbier, A. J. (2011). Students’ perceptions of patient safety during the transition from undergraduate to postgraduate training: an activity theory analysis. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 16(3), 347-358.

Deveugele, M., Derese, A., De Maesschaick, S., William, S., Dariel, V. M., & Maeseneer, D. J. (2005). Teaching communication skills to medical students, a challenge in curriculum. Patient Education and Counselling, 58(3), 265-270.

Gray, K., & Tobin, J. (2010). Introducing an online community into a clinical education setting: A pilot study of student and staff engagement and outcomes using blended learning. BMC Medical Education, 10(6), 1-9.

Hunt, M. T., & Glucksman, M. E. (1991). A review of 7 years of complaints in an inner-city accident and emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal, 8(1), 17-23.

Krishel, S., & Baraff, L. J. (1993). Effect of emergency department information on patient satisfaction. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 22(3), 568-572.

Lau, F. L. (2000). Can communication skills workshops for emergency department doctors improve patient satisfaction? Journal of Accident & Emergency Medicine, 17(4), 251–253.

Mehta, P. N. (2008). Communication skills-talking to parents. Indian Paediatrics, 45(4), 300-304.

O’Hagan, S., Manias, E., Elder, C., Pill, J., Woodward-Kon, R., McNamara, T., … McColl, G. (2014). What counts as effective communication in nursing? Evidence from nurse educators’ and clinicians’ feedback on nurse interactions with simulated patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(6), 1344-1356.

Rhee, K. J., & Bird, J. (1996). Perceptions and satisfaction with emergency department care. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 14(6), 679–683.

Rider, A., Hinrichs, M. M., & Lown, B. A. (2006). A model for communication skills assessment across the undergraduate curriculum. Medical Teacher, 28(5), 127-134.

Rowland-Morin, P. A., & Carroll, J. G. (1990). Verbal communication skills and patient satisfaction. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 13(2), 168-185.

Shendurnikar, N., & Thakkar, P. A. (2013). Communication skills to ensure patient satisfaction. The Indian Journal of Paediatrics, 80(11), 938-943.

Thompson, D. A., & Yarnold, P. R. (1996). Effects of actual waiting time, perceived waiting time, information delivery, and expressive quality on patient satisfaction in the emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 28(6), 657–665.

*Khoo Su Ann

Children’s Emergency Department,

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH),

100 Bukit Timah Road, 229899

Email: khoo.su.ann@kkh.com.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.