Cardiovascular Embryology

CHAPTER 1: CARDIOVASCULAR Embryology

Dr Sara Kashkouli Rahmanzadeh

NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine Department of Anatomy

Email: antsec@nus.edu.sg

1. Introduction and Overview

This chapter will take you through cardiovascular system’s development in our “How to Build a Human” series. It covers a comprehensive overview of the formation of the heart and its chambers, the development of blood vessels, and the details of fetal circulation.

Learning Objectives

Below are the overall learning objectives of this chapter:

-

- Understand the formation of the heart tube.

- Describe the development of the heart chambers.

- Identify the formation of blood vessels and embryonic vessels.

- Explain how these structures contribute to fetal circulation.

- Define the roles of foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus in fetal circulation.

Recap

We will continue our exploration of the cardiovascular system’s development in our series “How to Build a Human” series.

This section will provide a comprehensive overview of the formation of the heart and its chambers, the development of blood vessels, and the intricacies of fetal circulation.

Before we dive into the development of the cardiovascular system, let’s revisit some foundational concepts.

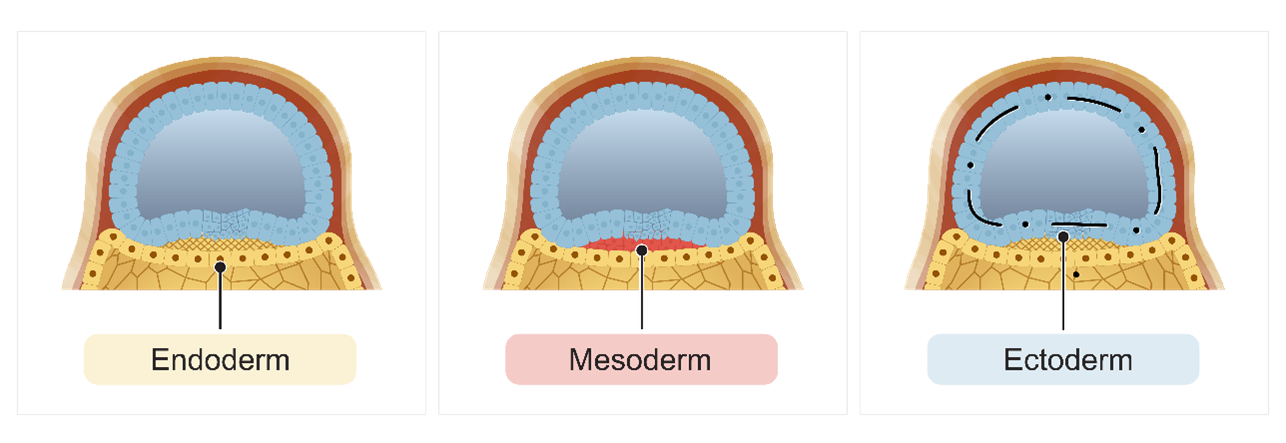

In our initial discussion on embryogenesis, we explored the process of gastrulation. This begins when cells from the epiblast layer migrate down the primitive groove. These migrating epiblast cells displace the hypoblast layer, creating a new layer known as the endoderm germ layer.

Once the endoderm germ layer has been established, more epiblast cells continue to migrate downward to form another new layer called the mesoderm germ layer. Finally, the remaining epiblast cells will differentiate into the ectoderm germ layer. This transformation marks the shift from a bilaminar disc, consisting of the epiblast and hypoblast layers, to a trilaminar disc with three distinct layers: the endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm germ layers.

These three germ layers are essential as they will differentiate into all the specific organ systems in the developing embryo.

1.1 Formation of the Heart Tube

In this section, we explore the process of heart tube formation during embryonic development. The cardiovascular system is among the first to emerge in the developing embryo, typically around the third week of development.

Understanding the timeline of organ system development provides valuable context. While memorizing specific dates or weeks isn’t necessary, knowing when these systems begin to form helps us appreciate the complexity and timing of embryonic growth. The heart tube’s formation marks a significant milestone, initiating the development of the cardiovascular system.

Embryonic Layers

Embryonic Layers: The Cardiogenic Area and Mesoderm Development

In this section, we’ll explore the early stages of embryonic development, focusing on the formation of germ layers. These layers play a crucial role in shaping the developing embryo. Let’s break it down step by step:

1. Germ Layers Overview

The developing embryo begins with three primary germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Our focus will be on mesoderm, which gives rise to various structures, including blood vessels and blood cells.

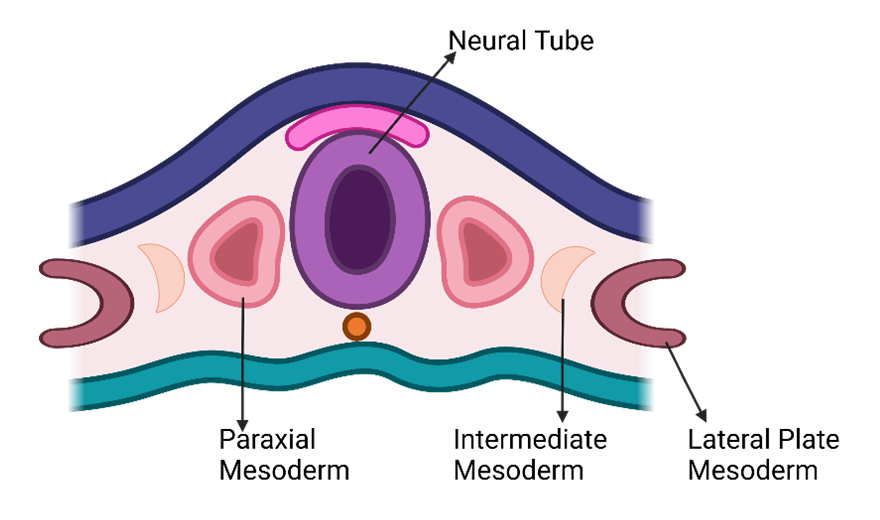

2. Mesoderm Subdivisions

Within the mesoderm, distinct regions emerge:

-

- Lateral Plate Mesoderm: Located alongside the developing neural tube, the lateral plate mesoderm contributes significantly to the cardiovascular system.

- Intermediate Mesoderm: Adjacent to the lateral plate mesoderm, the intermediate mesoderm plays a role in kidney and reproductive system development.

- Paraxial Mesoderm: Next to the intermediate mesoderm, the paraxial mesoderm gives rise to somites and skeletal muscle.

- Neural Tube and Notochord: The neural tube arises from the ectoderm and will become the central nervous system. The notochord provides structural support and influences tissue differentiation.

- Cardiogenic Area: As the embryo folds and curves, the cardiogenic area emerges near the cranial region. This area marks the beginning of cardiovascular system development. From here, blood vessels, blood cells, and a significant portion of the heart will originate.

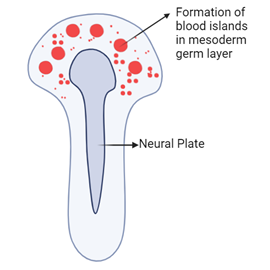

Formation of Blood Islands

Timing and Initial Formation

Around three weeks into embryonic development, the lateral plate mesoderm begins forming structures known as blood islands. Blood islands originate from precursor cells called angioblasts.

Role of Angioblasts and Vasculogenesis

Angioblasts are responsible for creating new blood vessels. This process is termed vasculogenesis. During vasculogenesis, angioblasts differentiate and form the initial blood vessels. This marks the beginning of the vascular system, which will eventually transport blood throughout the body.

Cell Signaling and Cardiogenic Cords

Cell signaling in the cardiogenic area (located in the cranial region of the embryo) causes the lateral plate mesoderm to differentiate into cardiogenic cords. These cords initially form from individual blood islands that merge together over time.

Development of the Cardiogenic Tube

As development continues, the cardiogenic cords develop a lumen and acquire a U-shaped or horseshoe-shaped appearance. This results in the formation of a continuous structure called the cardiogenic tube or endocardial tube.

Fusion and Formation of the Primitive Heart Tube

The endocardial tubes curve around the embryo and eventually fuse together. The fusion of the two endocardial tubes forms the primitive heart tube.

Embryo Folding and Anatomical Positioning

As the embryo folds, it shapes the developing organ systems, including the heart. The folding process brings the two separate endocardial tubes together, leading to the heart tube being positioned in its correct anatomical location within the thorax.

Concurrent Development of Organ Systems

Different organ systems, while discussed separately, develop concurrently.

The folding of the embryo not only shapes the heart but also affects the positioning and development of other organ systems.

Cardiogenic Field

Differentiation of Progenitor Cells

Progenitor cells start to differentiate in response to signals from the surrounding endoderm. These progenitor cells develop into myoblasts.

Formation of Myoblasts

Myoblasts surround the developing horseshoe-shaped tube within the cardiogenic field.

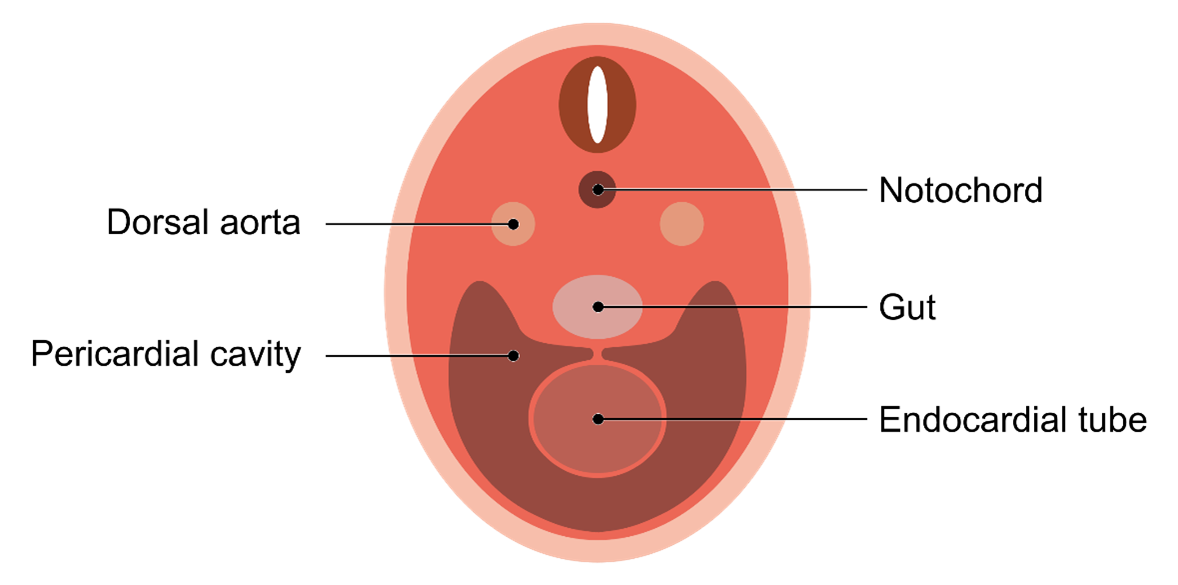

Expansion of the Primitive Heart Tube

The early heart tube expands into the newly forming pericardial cavity.

The primitive heart tube expands within the developing pericardial cavity. As it expands, it begins to establish connections with the dorsal aorta, which is located cranially.

Embryonic Folding and Organ Development

Embryonic folding occurs in both lateral and cephalocaudal directions. This folding process moves the heart into the thoracic region and brings different components of the cardiovascular system closer together.

Cross-Sectional View of Endocardial Tube

In cross-sectional images, the endocardial tube is visible and labeled on one side. As the embryo folds and curves, parts of the endocardial tube come together, initially forming a horseshoe shape and eventually rounding out and expanding within the pericardial cavity.

Positioning within the Thoracic Cavity

The developing heart tube and other structures, such as the neural tube and notochord expand and fold. Ultimately, these structures, including the heart tube, become positioned within the thoracic cavity of the developing embryo.

Primitive Heart Tube

Formation of the Primitive Heart Tube

The transition from small blood islands to the primitive heart tube involves several stages. Initially, the blood islands coalesce and form endocardial tubes. These endocardial tubes initially take on a horseshoe shape. Over time, they move closer together and fuse to form the primitive heart tube.

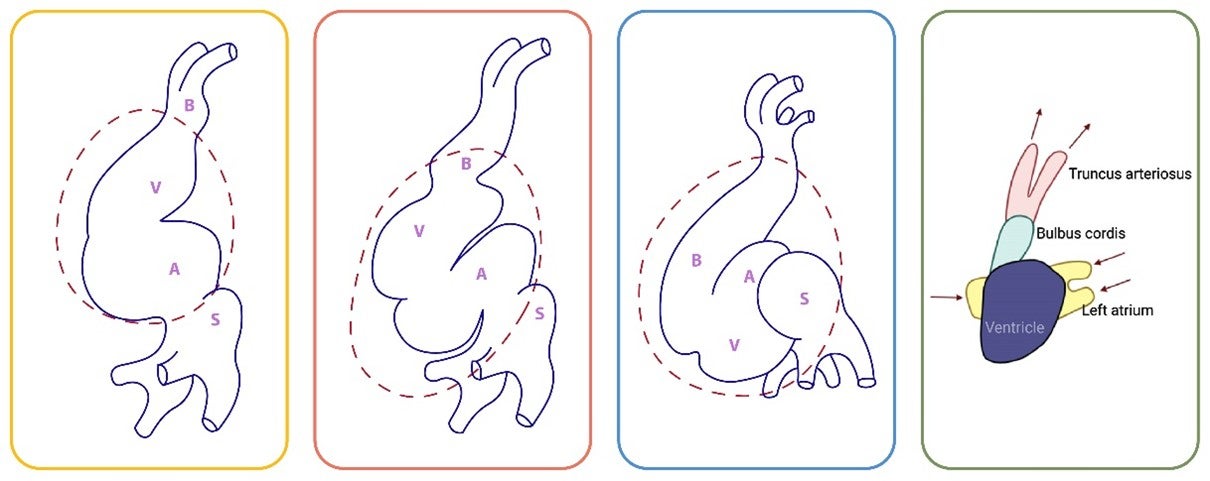

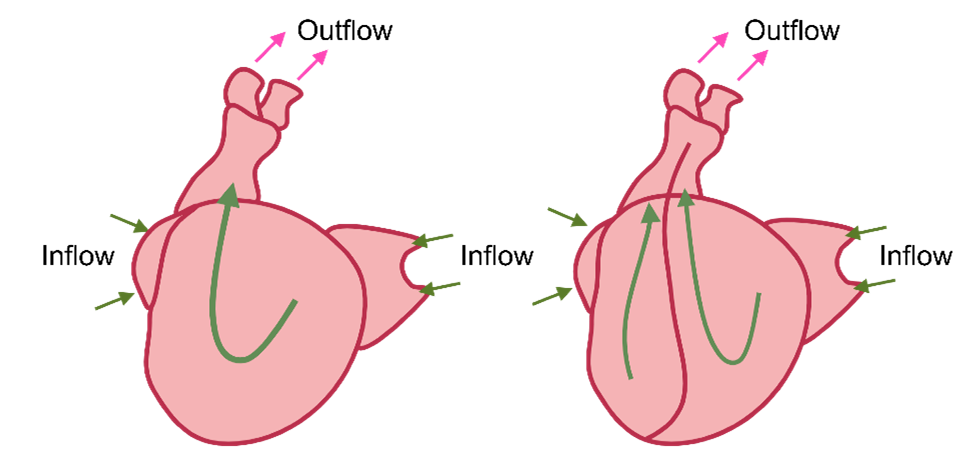

Cardiac Looping Process

To develop from a simple, straight tube into a more complex heart with four chambers, the primitive heart tube undergoes a process known as cardiac looping. Cardiac looping begins with a downward and forward movement.

Movement of Key Regions

Primitive heart tube folds to bring it from a straight tube to a folded shape ready to become four chambers.

The heart tube begins to fold and develops 2 bulges.

Cranial bulge

Bulbus cordis

Caudal bulge

Primitive ventricle

These continue to bend to create the cardiac (bulboventricular) loop during the fourth week of development.

This in particular is important as it allows for spatial orientation of the heart, heart chamber formation, and establishing a blood flow pattern.

The bulbus cordis and the truncus arteriosus are regions that move downward and forward during looping. This movement repositions the various components of the primitive heart tube, contributing to the development of the mature heart structure.

Formation of the Bulboventricular Loop

By the fourth week of development, the heart tube forms a structure known as the bulboventricular loop. This S-shaped loop begins to give the heart its more familiar orientation and structure.

Development of Heart Chambers

As looping progresses, the primitive atrium moves dorsally, and the bulbus cordis and ventricle shift ventrally and caudally. The primitive heart will eventually form the four chambers: right atrium, left atrium, right ventricle, and left ventricle.

Repositioning During Looping

During cardiac looping, the atrium and sinus venosus move to a more dorsal position compared to the truncus arteriosus, bulbus cordis, and the developing ventricle. As a result, the atrium ends up positioned more dorsal relative to the other heart components.

Formation of Ventricles and Outflow Tracts

The common atrium connects to the primitive ventricle via the atrioventricular canal. The primitive ventricle predominantly develops into the left ventricle, while the proximal parts of the bulbus cordis contribute to the formation of the right ventricle. Various sections of the primitive heart tube give rise to the outflow tracts. The truncus arteriosus forms the roots of the great vessels.

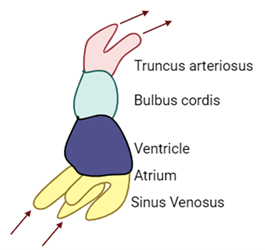

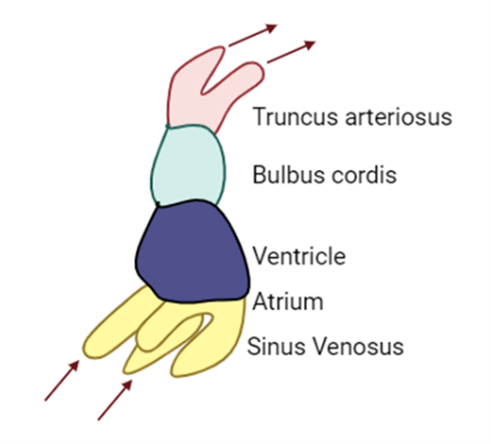

Main Components of the Developing Heart

The developing heart comprises six main parts:

-

- Aortic roots

- Truncus arteriosus

- Bulbus cordis

- Ventricle

- Atrium

- Sinus venosus

Developmental Significance

Each of these parts will eventually contribute to different aspects of the fully developed heart.

Further details of these components and their roles will be discussed in subsequent sections.

Primitive Circulation

Primitive Circulation:

-

- Outflow tracts

Dorsal aortae

- Truncus arteriosus

Pulmonary artery and ascending aorta

- Bulbus cordis

Right ventricle and outflow tracts

- Primitive ventricle

Left ventricle

- Primitive aorta

Right and left atria

- Sinus venosus

Inflow tracts from:

- Outflow tracts

-

-

- Common cardinal veins

- Umbilical veins

- Vitelline veins

-

Outflow Tracts of the Primitive Heart

The outflow tracts of the heart are crucial for understanding primitive circulation. Blood exits the heart through these tracts after being supplied to the heart. The outflow tracts are identified as the dorsal aortae, with one dorsal aorta on each side of the embryo.

Blood Flow Through the Heart

Blood enters the heart through the sinus venosus. It then moves through the primitive atrium, flows into the primitive ventricle, passes through the bulbus cordis, and continues through the truncus arteriosus. Finally, blood exits through the dorsal aortae to circulate to the rest of the embryo.

Developmental Changes

The truncus arteriosus will develop into the pulmonary arteries (also known as the pulmonary trunk) and the ascending aorta. The bulbus cordis will contribute to forming parts of the right ventricle and help establish the right and left outflow tracts. The primitive ventricle will evolve into the left ventricle. The primitive atrium will mature into the right and left atria. The sinus venosus will eventually form the inflow tracks for the heart.

Inflows to the Sinus Venosus

The sinus venosus has two horns: a right horn and a left horn.

Each horn receives blood from various veins, including the common cardinal veins, umbilical veins, and vitelline veins. At this developmental stage, the heart is still a primitive tube-like structure and does not yet resemble the fully developed heart with four distinct chambers. The transition from this simple structure to a mature heart involves complex changes, including the formation of four chambers and the reorganization of inflow and outflow tracts.

Future Developments

The sinus venosus has two horns: a right horn and a left horn.

Each horn receives blood from various veins, including the common cardinal veins, umbilical veins, and vitelline veins. At this developmental stage, the heart is still a primitive tube-like structure and does not yet resemble the fully developed heart with four distinct chambers. The transition from this simple structure to a mature heart involves complex changes, including the formation of four chambers and the reorganization of inflow and outflow tracts.

Formation of Chambers

Developmental Orientation

The heart develops in a downward and forward direction. It is crucial for this process to occur at the correct time and in the correct manner for the heart to achieve its expected orientation and structure.

Understanding the Heart Components

At this stage:

-

- B: Bulbus cordis

- P: Primitive ventricle

- A: Primitive atrium

- S: Sinus venosus

Looping Process

The heart starts as a simple tube. As it loops, the bulbus cordis and truncus arteriosus move downward and slightly to the right. This movement affects the positioning of the rest of the heart.

The downward movement of these structures causes the primitive ventricle to shift upward, forward, and to the left. Consequently, the primitive atrium is pulled backward and upward.

Transition to a Familiar Shape

By observing the transition from initial to final stages, you can see:

-

- The primitive atrium moves to a position above and adjacent to the bulbus cordis.

- The sinus venosus continues to feed into the primitive atrium.

This repositioning transforms the heart from a tubular shape into a form closer to the familiar heart shape with distinct chambers.

Heart Structure in Development

At this stage, the heart consists of:

-

- A common atrium (with a single atrial chamber).

- A common ventricle (a single ventricular chamber).

- The common atrium connects to the common ventricle via the atrioventricular canal, which will later evolve into separate atrial and ventricular chambers.

- The primitive ventricle will eventually develop into the left ventricle, while the proximal parts of the bulbus cordis will contribute to the formation of the right ventricle.

The transition from a straight tubular structure to a more complex heart involves the movement and repositioning of heart structures. This process ultimately results in the formation of distinct chambers, including the separation into right and left atria and ventricles, creating a more recognizable heart shape.

Sinus Venosus

-

- Sinus venosus is formed by the major embryonic veins (common cardinal, umbilical, and vitelline).

- Responsible for the inflow of blood to the primitive atrium, receives blood from sinus horns.

- With time, venous drainage is prioritized to the right side of the embryo and the left sinus horn becomes smaller and eventually forms the coronary sinus and drains the coronary veins into the right atrium. Right sinus horn becomes part of the IVC.

- A single pulmonary vein on the left side of the primitive atrium, divides to form 4 pulmonary veins.

- These become incorporated into the wall of the future left atrium and extend towards the developing lungs.

Primitive Circulation

In earlier stages of development, blood enters the heart through the sinus venosus, a structure located at the bottom of the developing heart, and exits through the dorsal aorta at the top.

Changes in Sinus Venosus

As development progresses, the venous drainage system shifts primarily to the right side of the embryo. The left horn of the sinus venosus gradually diminishes in size and significance and eventually forms the coronary sinus, which drains coronary veins into the right atrium in the adult heart.

Right Horn of Sinus Venosus

The right horn of the sinus venosus persists and undergoes further development. It enlarges and becomes incorporated into the inferior vena cava, which carries blood into the right atrium.

Development of Pulmonary Veins

Initially, a single pulmonary vein connects to the left side of the primitive atrium. As development progresses, this vein bifurcates to form the four pulmonary veins, which are observable in the adult heart. These pulmonary veins integrate into the wall of the developing left atrium and extend towards the developing lungs.

1.2 Heart Chambers

Initially, the developing heart begins as a simple heart tube, consisting of a common atrium and a common ventricle. As development progresses, this structure evolves into a more complex arrangement with four distinct chambers: two atria and two ventricles. Specifically, the heart will form a right atrium and a left atrium, as well as a right ventricle and a left ventricle. This transformation is a crucial step in the maturation of the heart, allowing it to effectively separate oxygenated and deoxygenated blood and efficiently manage circulatory function.

Formation of Atrial and Ventricular Septa

Initial Heart Structure

At the beginning of the fifth week of development, the heart consists of a single, continuous atrium and a single ventricle. This single chamber structure requires division into distinct right and left atria, and right and left ventricles.

Formation of Septa

The separation of the atria and ventricles involves the formation of septa, which are partitions that divide the heart into its four chambers. Septa (the plural of septum) grow inward from the endocardium (the inner lining of the heart) to create distinct chambers.

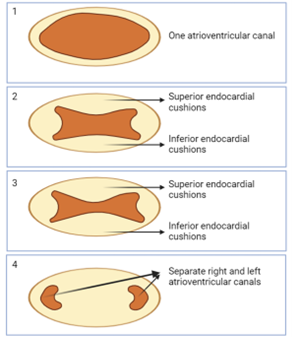

Development of Endocardial Cushions

-

- A muscular interventricular septum arises from the floor of the ventricular chambers as the 2 primitive ventricles begin to expand.

- The septum rises towards the endocardial cushions.

- As it is doing so, it creates a temporary interventricular foramen.

- The endocardial cushion extends inferiorly to complete the interventricular septum and close the interventricular foramen.

- Now the heart is four connected chambers.

Cell signaling directs groups of cells to migrate to specific areas, forming endocardial cushions. These cushions appear in the atrioventricular canal and begin to thicken, bulging inward toward the lumen of the canal. The thickening cushions on the superior and inferior aspects of the canal eventually grow toward each other.

Fusion of Endocardial Cushions

The endocardial cushions fuse, dividing the single atrioventricular canal into two distinct canals. This fusion effectively separates the primitive atrium from the primitive ventricle.

Separation into Atria and Ventricles

As the endocardial cushions continue to thicken and fuse, they create two separate atrioventricular canals. This process separates the primitive atrium into the right and left atria and the primitive ventricle into the right and left ventricles.

Development of Valves

Following the formation of the atrioventricular canals, these endocardial cushions contribute to the formation of heart valves. The atrioventricular valves are connected to the ventricular walls by chordae tendineae and papillary muscles. The atrioventricular valve on the left side develops into the bicuspid (or mitral) valve with two leaflets, while the right side forms the tricuspid valve with three leaflets.

Further Development

As development progresses, the heart also forms semilunar valves at the openings of the pulmonary trunk and aorta. The formation and arrangement of these valves ensure proper blood flow through the heart chambers and out to the systemic and pulmonary circulations.

Visualization

Understanding these structures may be challenging without visual aids. Observing heart specimens and models in the practical anatomy sessions will help clarify these developmental stages. Revisiting this section after seeing these structures in detail will enhance your comprehension of how the heart's chambers and valves form.

Development of Distinct Atria and Ventricles

At this stage in development, the heart has a single common atrium at the top and a single common ventricle at the bottom. The heart does not yet resemble the four-chambered structure of an adult heart with distinct left and right atria and left and right ventricles. Further septation is needed to achieve this distinct separation and to divide the common atrium into the left and right atria and the common ventricle into the left and right ventricles. This process ensures the formation of the four separate chambers seen in the adult heart.

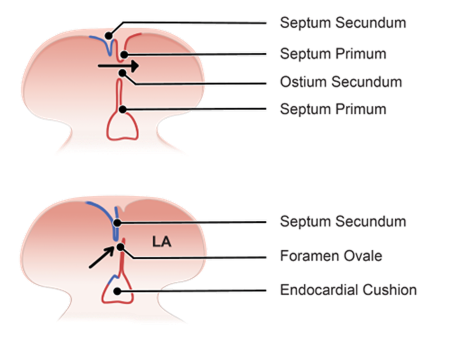

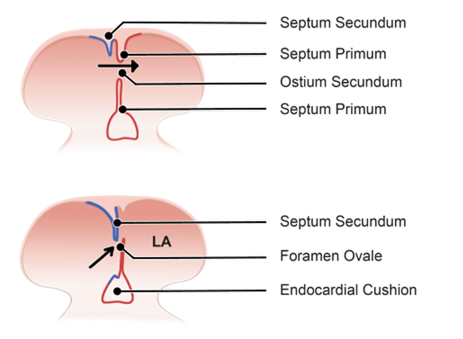

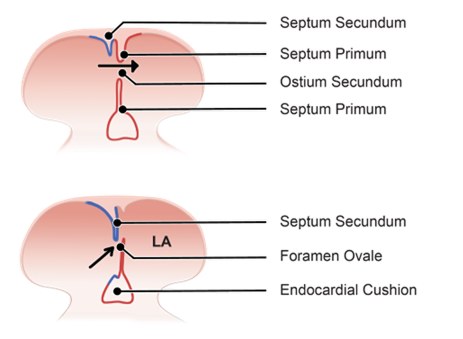

Separation of the Atria

Initial State

-

- New tissue forms in the roof of the primitive atrium = septum primum which extends down from the roof, growing towards the endocardial cushions to split the atrium into 2.

- The primitive atrium splits into left and right atria and the gap inferior to the septum primum is the ostium primum.

- Growth of the endocardial cushions and septum primum cause them to meet.

In the early stages, the heart consists of a single, continuous atrium and a single ventricle.

Formation of Septum Primum

A tissue ridge, known as the septum primum, begins to form from the roof of the primitive atrium. This septum extends downward toward the endocardial cushions, which are structures involved in the formation of heart valves and septa.

Creation of Ostium Primum

As the septum primum grows downward, it initially does not reach the endocardial cushions immediately. The opening or space left between the descending septum primum and the endocardial cushions is called the ostium primum. This space is temporary and exists only briefly during development.

Closure of Ostium Primum

Eventually, the septum primum reaches the endocardial cushions, closing ostium primum and effectively dividing the atrium into left and right sides.

Formation of Ostium Secundum

-

- Tissue growth from the roof of the atrium = septum secundum (grows towards the endocardial cushions).

- Gap = ostium secundum.

- Flap of the septum premium against septum secundum forms a one-way valve allowing blood to shunt from the right atrium to the left but not in reverse, this is foramen ovale.

- A change in pressure between atria at birth holds the septum primum closed against septum secundum and the foramen becomes permanently sealed.

As the septum primum continues to develop, another opening forms higher up, known as the ostium secundum. This opening allows for continued blood flow between the atria during fetal development, bypassing the developing lungs.

Significance of Ostium Secundum

The ostium secundum is crucial for allowing blood flow between the atria while the lungs are not yet functional. The development of the ostium secundum will be further explained in the next section.

Therefore, the separation of the atria begins with the formation of the septum primum, creating the ostium primum. As development progresses, the septum primum closes the ostium primum, while the ostium secundum forms to facilitate proper blood flow during fetal development.

Formation of Septum Secundum and Foramen Ovale

Formation of Septum Secundum

A second ridge of tissue, called the septum secundum, begins to grow downward from the roof of the developing atrium. This septum grows similarly to the septum primum, extending downward and positioning itself adjacent to the septum primum.

Interaction with Ostium Secundum

The septum secundum grows enough to partially cover the ostium secundum, an opening formed earlier by the septum primum. This partial coverage creates a new space between the septum secundum and the ostium secundum.

Formation of Foramen Ovale

The space between the septum secundum and the ostium secundum is known as the foramen ovale. Foramen ovale allows blood to flow from one atrium to the other, bypassing the developing lungs.

Function During Fetal Development

The foramen ovale facilitates the shunting of blood directly from one atrium to the other, bypassing the non-functioning and developing fetal lungs. The arrangement of the septa prevents backflow of blood in the opposite direction, ensuring efficient blood flow throughout the body.

Post-Birth Changes

At birth, the baby’s first breath causes a significant pressure change in the heart and lungs. This change causes the septum primum to press against the septum secundum, functionally closing the foramen ovale.

Formation of Fossa Ovalis

The closure of the foramen ovale leaves a residual structure known as the fossa ovalis, which is observable in adult hearts.

Patent Foramen Ovale

If the foramen ovale does not close properly, it can lead to a condition known as patent foramen ovale, which will be discussed later.

Importance of Proper Septation

The formation of the septa effectively separates the primitive atrium into distinct right and left atria. Incomplete septation can result in atrial septal defects, leading to abnormal blood shunting between the atria and other associated complications.

Separation of the Ventricles

Initial State

Early in development, the heart has a single, undivided ventricle.

Formation of the Interventricular Septum

A muscular interventricular septum begins to develop from the floor of the ventricular chamber. This septum rises towards the endocardial cushions, separating the right and left ventricles.

Interventricular Foramen

As the interventricular septum rises, it creates a temporary space known as the interventricular foramen. This space exists until the septum completes its growth and reaches the endocardial cushions.

Completion of Septation

The interventricular septum eventually closes off the interventricular foramen, fully separating the right and left ventricles.

Simultaneous Development

As the ventricles expand, structures such as the papillary muscles and chordae tendineae form within them. These structures are crucial for the proper functioning of the atrioventricular valves and preventing the backflow of blood.

Final Structure

By the end of this process, the heart will have two distinct ventricles: the right and left ventricles.

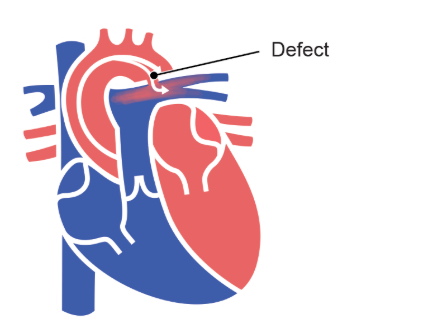

Ventricular Septal Defect

Incomplete closure of the interventricular foramen can lead to a ventricular septal defect.

Ventricular septal defect results in abnormal mixing of blood between the ventricles, similar to issues seen with atrial septal defects.

Blood Flow Through the Primitive Heart

Inflow Tract

-

- Common cardinal vein + umbilical vein + vitelline vein feed into right and left horn of sinus venosus.

- Left horn of sinus venosus break down and gives rise to the coronary sinus.

- Right horn of sinus venosus ➡

-

-

- Umbilical vein degenerates

- Common cardinal vein becomes superior vena cava

- Vitelline vein becomes inferior vena cava

-

-

- Outflow tract of the primitive heart must split into 2 to pass blood from the ventricles to the pulmonary and systemic circulatory systems.

In early development, blood flows into the heart through the sinus venosus which receives blood from three primary veins: the common cardinal veins, the umbilical veins, and the vitelline veins. Sinus venosus has a right horn and the left horn.

Left Horn of Sinus Venosus

The left horn of sinus venosus receives blood from the common cardinal veins, umbilical veins, and vitelline veins. As development progresses, these veins break down and the left horn will eventually become the coronary sinus.

Right Horn of Sinus Venosus

The right horn of sinus venosus also receives blood from the common cardinal veins, umbilical veins, and vitelline veins. While the umbilical vein ultimately degenerates, the common cardinal vein develops into the superior vena cava, and the vitelline vein contributes to the formation of the inferior vena cava.

Outflow Tract Development

Below the truncus arteriosus, the bulbus cordis also develops ridges on its inner walls. And the ridges on both truncus arteriosus and bulbus cordis form septa. The septa from these ridges will intertwine, creating the pulmonary trunk and the aorta. The direction of blood flow from the left ventricle is into the aortic arch, and from the right ventricle into the pulmonary trunk.

These evolving structures will guide the formation of the mature heart's inflow and outflow tracts.

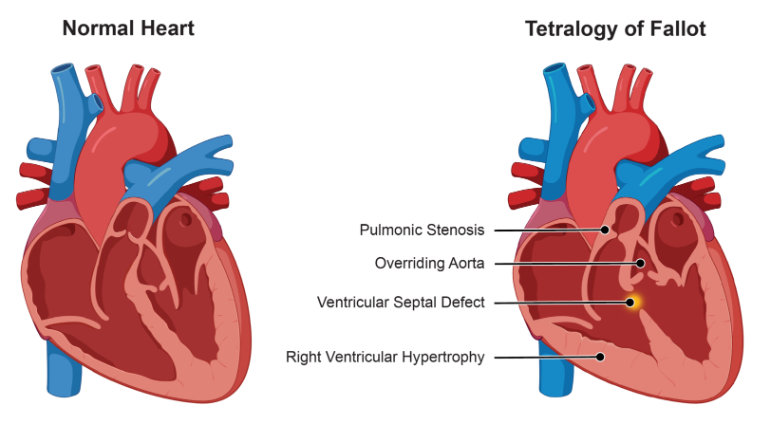

Tetralogy of Fallot

Tetralogy of Fallot is a congenital heart defect resulting from abnormal development of the heart structures, specifically involving truncus arteriosus and bulbus cordis. This condition involves four primary cardiovascular anomalies that will affect the structure and function of the heart:

-

- Overriding Aorta: The aorta is abnormally positioned, overriding both the right and left ventricles instead of arising solely from the left ventricle. This allows blood from both ventricles (including deoxygenated blood from the right ventricle) to flow into the aorta, resulting in systemic circulation of mixed oxygenated and deoxygenated blood.

- Pulmonary Stenosis: This refers to the narrowing of the pulmonary valve or the outflow tract from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery, restricting blood flow to the lungs. The degree of stenosis determines how much blood reaches the lungs, directly affecting oxygenation levels.

- Ventricular Septal Defect: A hole in the septum between the right and left ventricles allows oxygen-poor blood from the right ventricle to mix with oxygen-rich blood from the left ventricle. This inefficiency increases the heart’s workload and causes improper circulation.

- Right Ventricular Hypertrophy: The walls of the right ventricle thicken in response to the increased pressure that is required to pump blood through the narrowed pulmonary outflow tract. Over time, this thickening can lead to reduced right ventricular function.

Treatment and Management

Managing Tetralogy of Fallot typically requires both immediate care for symptoms and surgical correction of defects. Key components of the treatment include:

-

- Oxygen Therapy: Providing supplemental oxygen to ensure adequate oxygenation of tissues, especially in infants experiencing cyanosis (bluish skin due to low oxygen levels).

- Surgical Intervention: Surgery is the mainstay of treatment and involves repairing the four defects. Surgical procedures typically include:

-

-

- Closing the Ventricular Septal Defect: This is done to prevent the mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood between the ventricles. A patch is placed over the defect to close the opening.

- Relieving Pulmonary Stenosis: Surgeons may enlarge or replace the narrowed pulmonary valve or the outflow tract to restore proper blood flow to the lungs. This treatment ensures that blood can flow freely from the right ventricle to the pulmonary arteries.

-

-

- Additional Surgical Considerations: In cases where the right ventricle has become severely hypertrophied, additional interventions may be needed to improve ventricular function over time.

Prognosis and Follow-up

With proper surgical treatment, most children with Tetralogy of Fallot go on to lead relatively normal lives. However, lifelong follow-up is necessary to monitor heart function, especially if residual issues like pulmonary valve regurgitation or arrhythmias occur.

1.3 Blood Vessels: Vasculogenesis and Angiogenesis

With a clearer understanding of how the four distinct heart chambers develop, we can now turn our attention to the formation of blood vessels, a crucial aspect of the cardiovascular system. The development of blood vessels involves two primary processes: vasculogenesis and angiogenesis.

-

- Vasculogenesis is the process through which new blood vessels are formed from mesodermal progenitor cells during embryonic development.

-

-

- These progenitor cells differentiate into hemangioblasts, which further develop into two distinct types of cells:

-

-

-

-

- Hematopoietic stem cells, which are responsible for the formation of blood cells.

- Angioblasts, which differentiate into endothelial cells, forming the walls of the blood vessels.

-

-

Initially, vasculogenesis occurs in various isolated regions of the developing embryo. As these sites of vasculogenesis progress, they eventually merge to create a connected network of blood vessels.

-

- Angiogenesis follows vasculogenesis and refers to the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing blood vessels, primarily through the s the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells, which form new capillaries.

Angiogenesis is crucial not only during the developmental stages but also throughout life. It plays a significant role in wound healing and in responding to the body's changing demands, such as those related to tissue growth and repair.

As development continues, the liver and later the bone marrow will become the primary sites for hematopoiesis, further supporting the evolving vascular network. Both vasculogenesis and angiogenesis are essential for establishing and maintaining an effective vascular system, facilitating proper circulation, and supporting overall health and development.

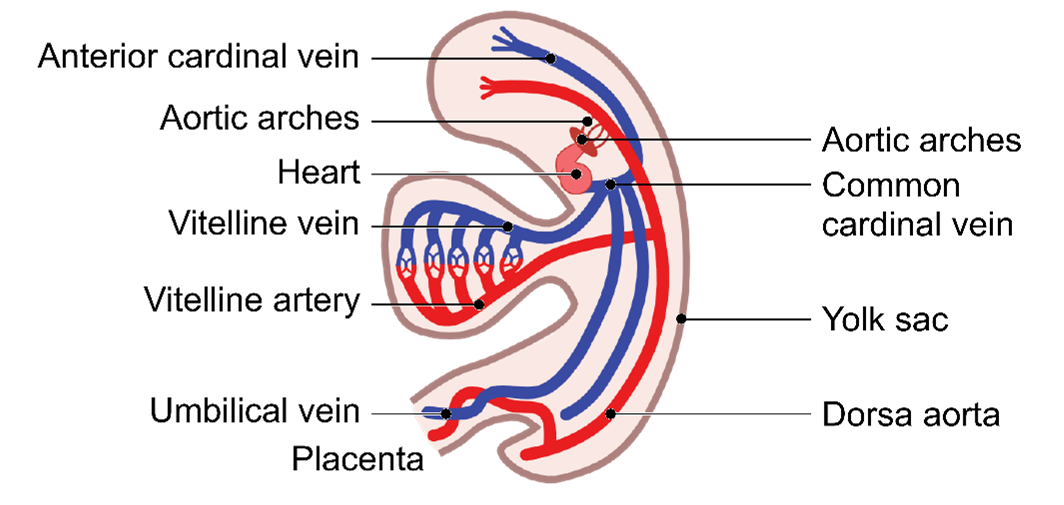

Embryonic Vessels

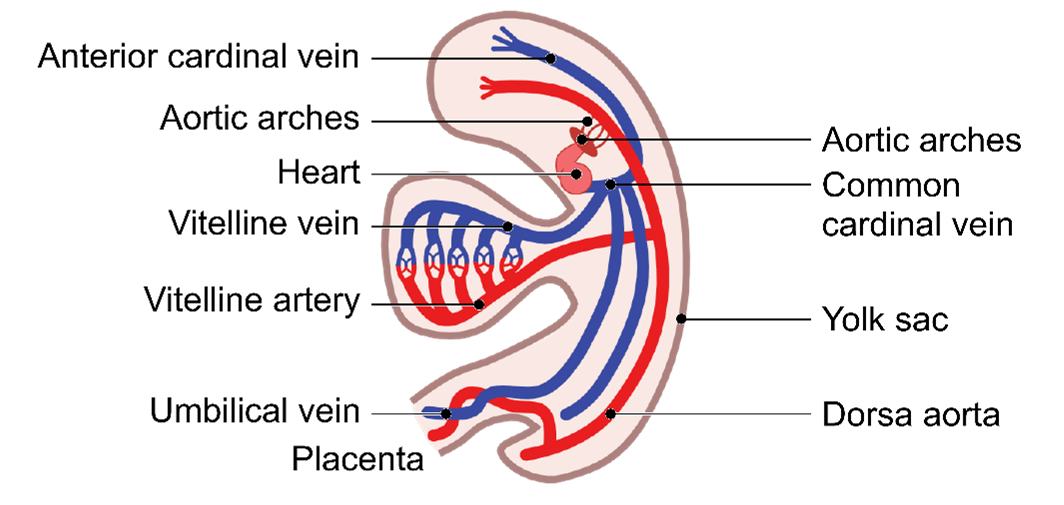

The development of embryonic vessels involves three key types: the cardinal vessels, the umbilical vessels, and the vitelline vessels. Each of these vessels has specific roles during the embryonic stage:

-

- Cardinal Vessels: These are the primary veins responsible for draining blood from the body back to the heart.

- Umbilical Vessels: This includes the umbilical arteries and the umbilical vein, which transport blood between the fetus and the placenta, facilitating the exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products.

- Vitelline Vessels: These vessels are involved in supplying blood to and from the yolk sac, an essential source of nutrients during early development.

Each vessel type plays an important role in the embryonic stage, supporting the developing cardiovascular system.

Vitelline Vessels

-

- Vitelline vessels = flow of blood between embryo and the yolk sac.

- Vitelline arteries: some degenerate and some remain as the 3 anterior branches of the abdominal aorta.

- Vitelline veins: give rise to the hepatic veins of the liver.

Vitelline Circulation

This circulation is crucial for the exchange of nutrients and waste between the embryo and the yolk sac. The vitelline vessels consist of two main types of vessels: the vitelline arteries and the vitelline veins.

Vitelline Arteries

These arteries branch off from the dorsal aorta and contribute to the development of the key vascular architecture. While most vitelline arteries degenerate, a few persist and fuse to form the major arteries that supply the abdominal organs:

-

- Celiac Trunk

- Superior Mesenteric Artery

- Inferior Mesenteric Artery

These arteries supply the abdominal region and will be revisited in the context of digestive system development.

Vitelline Veins

These veins give rise to the hepatic veins of the liver, which drain blood from the liver.

Umbilical Vessels

-

- Umbilical vessels = flow of blood between the chorion of the placenta and the embryo.

- Umbilical arteries ➡ Carry poorly oxygenated blood to the placenta.

- Umbilical veins ➡ Carry oxygenated blood to the heart of the embryo.

| Postnatally | Some umbilical arteries persist as the internal iliac/superior vesical arteries. Others, become ligaments. |

| Umbilical vein becomes ligamentum teres. |

Umbilical Circulation

This circulation involves the flow of blood between the developing placenta and the embryo and it is facilitated by the umbilical vessels, which include:

-

- Umbilical Arteries: These vessels carry deoxygenated blood from the embryo to the placenta and play an important role in removing waste products from the developing embryo.

- Umbilical Vein: This vessel transports oxygenated blood from the placenta to the embryo's developing heart and later to the developing liver.

Ductus Venosus

This is a specialized structure that forms as development progresses. It carries approximately half the blood volume from the umbilical vein directly to the inferior vena cava, bypassing the liver. This mechanism helps preferentially direct highly oxygenated blood to vital areas, such as the fetal brain.

Postnatal Changes

Following birth, several embryonic vessels undergo transformation as they lose their role in fetal circulation and adapt to serve structural purposes in the adult body.

-

- Umbilical Arteries: After birth, most of the umbilical arteries degenerate, but segments persist and contribute to important structures:

-

- Internal Iliac Arteries: Proximal portions of the umbilical arteries remain functional and continue as branches of the internal iliac arteries, supplying blood to the pelvis.

- Superior Vesical Arteries: The proximal segments also form the superior vesical arteries, which supply the urinary bladder.

- Median Umbilical Ligaments: The distal portions of the umbilical arteries transform into fibrous cords known as the median umbilical ligaments, which run along the inner surface of the anterior abdominal wall.

-

- Umbilical Vein: After birth, the umbilical vein loses its role in circulation, gradually closing off and becoming the ligamentum teres (or round ligament of the liver), which is located within the falciform ligament of the liver. This structure no longer carries blood but remains as a fibrous remnant.

- Umbilical Arteries: After birth, most of the umbilical arteries degenerate, but segments persist and contribute to important structures:

These transformations of embryonic vessels highlight how structures crucial for fetal circulation are repurposed to serve anatomical and structural functions in the adult body.

Cardinal Veins

Common Cardinal Veins

The common cardinal veins are paired embryonic veins that play a crucial role in establishing the venous system, connecting the major veins to the primitive atrium of the heart tube.

Superior Cardinal Veins

These veins drain blood from the upper regions of the embryo, including the head, neck, and upper limbs. They eventually contribute to the formation of veins that return blood from the upper body to the heart.

Inferior Cardinal Veins

These veins drain blood from the lower regions of the body, including the abdomen, pelvis, and lower limbs. As development progresses, they are involved in forming part of the venous system that returns blood from the lower body.

Developmental Progression

Throughout development, specific portions of the cardinal veins give rise to major veins in the adult venous system, including:

-

- Inferior Vena Cava: Formed in part by segments of the inferior cardinal veins, the inferior vena cava is responsible for returning deoxygenated blood from the lower body to the heart.

- Superior Vena Cava: Derived primarily from the right superior cardinal vein and other nearby structures, the superior vena cava carries deoxygenated blood from the upper body to the right atrium of the heart.

- Brachiocephalic Veins: Formed by the fusion of portions of the superior cardinal veins, these veins help transport blood from the head, neck, and arms to the superior vena cava.

- Azygos and Hemiazygos Veins: These veins arise from segments of the superior and inferior cardinal veins and are essential for venous drainage from the thoracic walls, providing an alternate pathway for blood to return to the heart if the inferior vena cava or superior vena cava is obstructed.

Persistent Branches

Some branches of the cardinal veins remain as s functional veins in the adult circulatory system, including:

-

- Renal Veins: Derived from portions of the posterior cardinal veins, they drain blood from the kidneys to the inferior vena cava.

- Suprarenal Veins: These veins, responsible for draining blood from the adrenal (suprarenal) glands, are partly derived from the subcardinal and posterior cardinal veins.

- Gonadal Veins: Originating from the subcardinal veins, the gonadal veins drain blood from the ovaries or testes to the inferior vena cava (right gonadal vein) or the left renal vein (left gonadal vein).

These cardinal veins are integral to the formation of the adult venous system and their derivatives continue to play essential roles in venous drainage system throughout the body.

1.4 Fetal Circulation

Having covered the development of primitive circulation, we can now explore fetal circulation. This section will explore how the circulatory system operates within the developing fetus, focusing on the unique adaptations that support fetal growth and development.

Flow of Oxygenated Blood in the Fetus

To understand how oxygenated blood circulates in the fetus, we can trace its journey from the placenta:

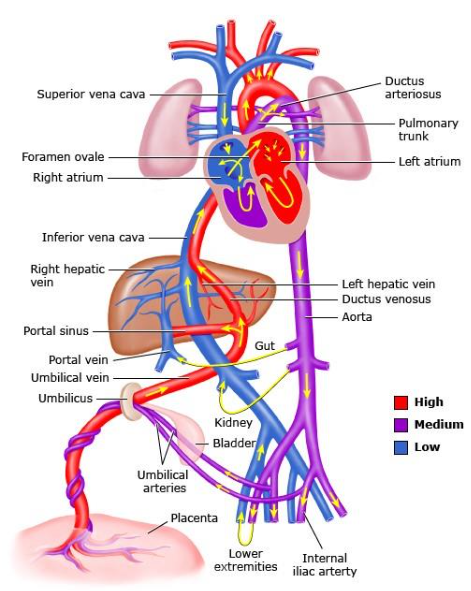

Figure 4-1. Flow of Oxygenated Blood from the Placenta to the Fetus. Graphic 66765 Version 5.0.

© 2024 UpToDate, Inc. and/or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved.

-

- Flow of oxygenated blood from the placenta

- Umbilical vein ➡ half enters liver

-

-

- Half is redirected by ductus venosus to the inferior vena cava (bypassing the liver)

- Right atrium

- Left atrium (through foramen ovale)

- Left ventricle

- Aorta

-

-

- Flow of deoxygenated blood from the SVC

-

-

- Right atrium (poorly oxygenated + well oxygenated blood mix, lowering the oxygen saturation)

- Right ventricle (blood passes through ductus arteriosus into the descending aorta)

-

Umbilical Vein

Oxygenated blood from the placenta enters the fetus through the umbilical vein, which transports nutrients and oxygen.

Liver and Ductus Venosus

A portion of the blood flows into the liver for metabolic support, while most bypasses the liver through ductus venosus, shunting directly to the inferior vena cava.

Inferior Vena Cava

The blood that bypasses the liver remains highly oxygenated as it travels to the right atrium of the heart.

Right Atrium

Blood from the inferior vena cava enters the right atrium AND is then shunted through the foramen ovale into the left atrium, bypassing the lungs.

Left Ventricle

The oxygenated blood is pumped from the left ventricle into the aorta for systemic circulation. It then circulates through the rest of the body, delivering oxygen-rich blood to developing tissues.

Superior Vena Cava

Deoxygenated blood from the superior vena cava and the coronary sinus also enters the right atrium. This blood mixes with the oxygenated blood coming from the ductus venosus, slightly reducing overall oxygen saturation.

Right Ventricle

Blood flows from the right atrium into the right ventricle. Blood that enters the right ventricle then flows into the pulmonary artery. However, most of the blood bypasses the non-functioning fetal lungs through ductus arteriosus.

Ductus Arteriosus

Most of the blood bypasses pulmonary circulation via the ductus arteriosus. This vessel allows blood to flow from the pulmonary artery directly into the aorta, ensuring it contributes to systemic circulation.

Aorta

Blood entering the aorta from the ductus arteriosus is distributed to the developing structures in the fetus through systemic circulation.

Return to Placenta

Finally, deoxygenated blood returns to the placenta through the umbilical arteries, completing the circulation cycle.

This pathway ensures that oxygenated blood from the placenta is effectively distributed throughout the fetus while bypassing the non-functioning lungs.

Ductus Venosus

Figure 4-2. Ductus Venosus in the Developing Fetus. Graphic 66765 Version 5.0.

© 2024 UpToDate, Inc. and/or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved.

-

- Ductus venosus shunts blood from the umbilical vein to the inferior vena cava bypassing the liver.

- After birth, a sphincter at the umbilical vein end of the ductus venosus closes.

- Ductus venosus will slowly degenerate and become the ligamentum venosum.

- When umbilical circulation stops, the umbilical vein will also degenerate and become the round ligament.

- Umbilical arteries; some will persist, and some become umbilical ligaments.

Function of Ductus Venosus

The ductus venosus shunts oxygenated blood from the umbilical vein directly to the inferior vena cava, bypassing the liver to expedite blood flow to the tissues of the body.

Post-Birth Changes

At birth, a sphincter at the umbilical end of the ductus venosus begins to constrict. This constriction leads to the obliteration of the ductus venosus. The ductus venosus ultimately becomes a fibrous remnant known as the ligamentum venosum. This transformation occurs as the liver assumes its full metabolic role.

Changes in Umbilical Circulation

As umbilical circulation ceases after birth, the umbilical vein becomes non-functional.

The umbilical vein closes off and becomes the ligamentum teres (or the round ligament of the liver), lying within the falciform ligament.

Umbilical Arteries

Portions of the umbilical arteries persist and become:

-

- Superior vesicle arteries supplying the urinary bladder.

- The remaining umbilical arteries degenerate and form the median umbilical ligaments.

Adaptability of the Cardiovascular System

The transition from fetal to postnatal circulation highlights the adaptability of the cardiovascular system. It effectively responds to the changing demands and functions outside the womb, ensuring continued adaptation and support for the body.

1.5 Foramen Ovale

In this section, we will explore the foramen ovale, focusing on its formation, functional role, and the changes it undergoes after birth. The foramen ovale is a key fetal structure that allows blood to flow from the right atrium to the left atrium.

Figure 5-1. Foramen Ovale in the Developing Fetus. Graphic 66765 Version 5.0.

© 2024 UpToDate, Inc. and/or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved.

-

- After the first breath the reduction in pulmonary vascular resistance and subsequent flow of blood through the pulmonary circulation increases the pressure in the left atrium.

- As the pressure in the left atrium is now higher than in the right atrium the septum primum is pushed up again the septum secundum, thus functionally closing the foramen ovale.

- Anatomical closure is usually completed within the next 6 months.

- In the adult heart a depression called the fossa ovalis remains upon the interior of the right atrium.

At birth, when the newborn takes its first breath, there is a significant decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance. This change increases blood flow to the lungs and results in a higher pressure in the left atrium compared to the right atrium. As a result, the septum primum is pushed against the septum secundum, effectively sealing the foramen ovale.

Over the following months, this functional closure becomes an anatomical one, leaving behind a depression known as the fossa ovalis on the inner wall of the right atrium. This remnant of the foramen ovale can be observed in specimens of the heart and serves as evidence of the transition from fetal to postnatal circulation.

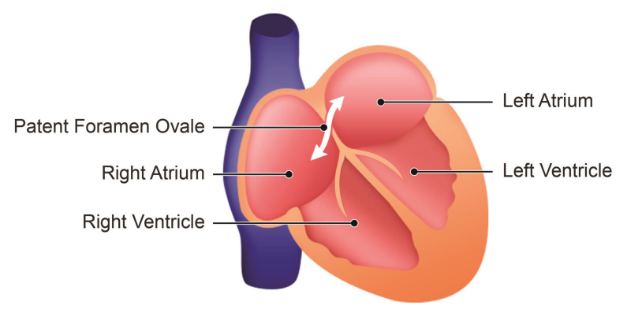

Patent Foramen Ovale

A patent foramen ovale occurs when the foramen ovale fails to close completely after birth, allowing blood to pass between the left and right atria.

-

- Atrial septal defect.

- Failure of foramen ovale to close anatomically.

- Backflow of blood can occur from left to right under certain circumstances which increases pressure in the thorax.

- Might occur during sneezing or coughing etc.

- Treatment varies with symptoms.

- Generally, no treatment is necessary.

Potential Effects

This incomplete closure can permit some degree of shunting, or backflow, of blood from the left atrium to the right atrium.

Symptoms and Triggers

In many cases, a patent foramen ovale is asymptomatic and does not cause noticeable issues. However, certain activities that increase thoracic pressure, such as sneezing or coughing, might temporarily exacerbate the shunting effect.

Treatment

Generally, individuals with a patent foramen ovale do not experience significant symptoms and may not require intervention.

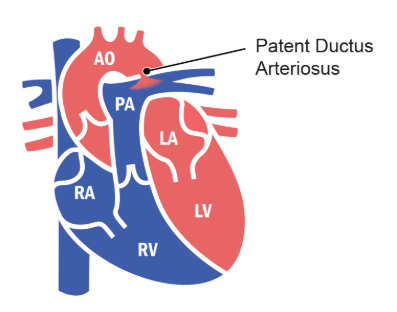

Ductus Arteriosus

In addition to discussing the various fetal circulatory structures, it's important to explore the ductus arteriosus. This section will provide a detailed look at the ductus arteriosus, its role in fetal circulation, and the changes it undergoes after birth.

-

- Attachment of distal aspect of pulmonary trunk to inferior aspect of aorta.

- Attachment exists until birth when it closes and eventually forms ligamentum arteriosum.

- It functions to shunt blood directly from the right ventricle to the aorta so it bypasses the fetal lungs.

- Blood from the aorta then continues to the umbilical arteries.

Role and Closure of the Ductus Arteriosus

Role During Fetal Development

During fetal development, the ductus arteriosus connects the distal end of the pulmonary trunk to the inferior aspect of the aorta. This vessel allows blood to bypass the non-functioning fetal lungs by directing right ventricular outflow directly into systemic circulation, efficiently supplying the rest of the fetus’ body.

Changes at Birth

With the onset of breathing and increased oxygen saturation at birth, biochemical changes induce the ductus arteriosus to constrict. This constriction redirects blood flow to the now-functioning lungs for oxygenation.

Postnatal Closure

Typically, the ductus arteriosus undergoes physiological closure within a few days after birth. It then gradually undergoes anatomical closure over the next few months, eventually becoming a fibrous remnant known as the ligamentum arteriosum.

Patent Ductus Arteriosus

Patent ductus arteriosus occurs when the ductus arteriosus fails to close properly after birth, leading to abnormal mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood.

-

- Oxygenated blood from the aorta mixes with the deoxygenated blood from the pulmonary arteries.

- Can cause tachypnea, tachycardia, cyanosis, labored breathing.

- Likely to occur in premature infants.

- Surgical or pharmacological treatment.

Symptoms

Infants with patent ductus arteriosus may exhibit symptoms such as rapid breathing, elevated heart rate, or cyanosis (bluish skin tone) due to insufficient oxygenation.

Association with Prematurity

Patent ductus arteriosus is more commonly observed in premature infants, as their vessels are less likely to close naturally.

Treatment Options

Persistent patent ductus arteriosus, especially when affecting respiratory function, may require medical or surgical intervention to restore proper oxygenation and circulatory efficiency.

For further study, you can find detailed notes on embryology, systemic, and regional anatomy on my website, learnanatome.com (LEARNANATOME.com). The site also includes a section where you can ask questions anonymously, which can be a useful tool for your revision. |

1.6 Summary

Key Stages of Cardiovascular Development

1. Formation of the Heart Tube

The heart begins as a simple tubular structure, which undergoes looping and septation to form four chambers: two atria and two ventricles. The heart tube’s transformation into a four-chambered organ is crucial for efficient separation of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood.

2. Development of Septa and Valves

Septation divides the heart’s chambers, while the endocardial cushions contribute to the formation of the heart’s valves. These structures ensure unidirectional blood flow through the heart and separate the systemic and pulmonary circulations.

3. Blood Vessel Formation

Blood vessels develop through two processes:

-

- Vasculogenesis: Formation of vessels from mesodermal progenitor cells, creating initial networks.

- Angiogenesis: Growth of vessels from pre-existing structures, which supports both prenatal development and lifelong tissue repair.

The major embryonic vessels—cardinal, umbilical, and vitelline—eventually adapt into structures of the adult venous system, supplying blood to the body.

4. Fetal Circulation

The fetal circulatory system is specially adapted to receive oxygen from the placenta rather than the lungs, with three major shunts facilitating this:

-

- Ductus Venosus: Allows oxygenated blood to bypass the liver and enter the heart directly.

- Foramen Ovale: Shunts blood from the right atrium to the left atrium, bypassing the lungs.

- Ductus Arteriosus: Directs blood from the pulmonary artery to the aorta, again bypassing the non-functional fetal lungs.

At birth, these shunts close as the newborn takes its first breaths, transitioning the circulatory system to one that relies on lung oxygenation.

Key Congenital Conditions

1. Tetralogy of Fallot

A combination of four defects affecting blood flow and oxygenation. TOF requires surgical correction to ensure proper blood circulation.

2. Patent Foramen Ovale

Occurs if the foramen ovale fails to close, occasionally allowing blood to flow between atria postnatally.

3. Patent Ductus Arteriosus

A condition where the ductus arteriosus remains open after birth, leading to mixed blood circulation and potential oxygenation issues, especially in premature infants.

Postnatal Adaptations

Following birth, the fetal vessels adapt into structures suited for postnatal life:

-

- Umbilical Vein becomes the ligamentum teres in the liver.

- Ductus Venosus becomes the ligamentum venosum.

- Ductus Arteriosus becomes the ligamentum arteriosum.

These postnatal transformations highlight the adaptability of the cardiovascular system in meeting the differing oxygenation needs of prenatal and postnatal life.

1.7 Quiz

Quiz

Please attempt this quiz to review the concepts you have learned.

- The myocardium, or muscle layer of the heart, is primarily a derivative of which one of the following embryonic cells?

- Neural crest cells

- Mesodermal cells

- Endodermal cells

- Ectodermal cells

- Which one of the following best explains why the foramen ovale remains open during fetal development but closes after birth?

- Increased blood pressure in the right atrium in fetal life and increased left atrial pressure postnatally

- Decreased vascular resistance in the lungs at birth, increasing left atrial pressure

- Low oxygen levels in the fetus inhibit closure, whereas oxygen levels at birth induce closure

- Growth of the left atrium at birth shifts the foramen ovale, causing closure

- Which congenital condition would most likely result if the endocardial cushions fail to fuse completely during heart development?

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Ventricular Septal Defect

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus

- Atrioventricular Septal Defect

- If the ductus arteriosus fails to close after birth, what would be the most likely physiological consequence?

- Increased pulmonary blood flow, potentially leading to pulmonary hypertension

- Decreased oxygenated blood reaching systemic circulation, leading to cyanosis

- Reduced venous return to the heart, impairing cardiac output

- Increased resistance in the left ventricle, resulting in left ventricular hypertrophy

- Which of the following mechanisms would most likely contribute to the thickening of the right ventricular wall in Tetralogy of Fallot?

- Higher pressure needed to pump blood through the narrowed pulmonary outflow tract

- Increased mixing of deoxygenated and oxygenated blood through the overriding aorta

- The shunting of blood through the patent foramen ovale

- Lower systemic vascular resistance, increasing right ventricular workload

1.8 Quiz Answers

Quiz Answers

1. b.

The myocardium develops from mesodermal cells, specifically from the lateral plate mesoderm. This mesodermal origin forms the muscular layer of the heart, enabling the contractions necessary for blood circulation.

2. b.

At birth, pulmonary vascular resistance decreases as the lungs expand with air. This leads to increased blood flow to the lungs and higher left atrial pressure, pressing the septum primum against the septum secundum, effectively closing the foramen ovale.

3. d.

Incomplete fusion of the endocardial cushions can lead to an atrioventricular septal defect, where there is an abnormal connection between the atria and ventricles. This defect often affects both the atrial and ventricular septa, disrupting normal blood flow between chambers.

4. a.

A patent ductus arteriosus allows oxygenated blood from the aorta to mix back into the pulmonary artery, leading to increased pulmonary blood flow. This can cause pulmonary hypertension due to the excess volume and pressure in the pulmonary circulation.

5. a.

Right ventricular hypertrophy develops because the narrowed pulmonary outflow tract (pulmonary stenosis) requires the right ventricle to generate higher pressure to push blood through to the lungs. This increased workload causes thickening of the right ventricular wall.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine Education Technology Team for helping me with instructional design and multimedia production. Additionally, this book utilized BioRender for creating scientific illustrations.

Drop us an email at medbox77@nus.edu.sg for any issues with the book.

® National University of Singapore. All rights reserved.